Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride (Monograph)

Drug class: Histamine H2-Antagonists

Introduction

Histamine H2 receptor antagonist.

Uses for Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride

Duodenal Ulcer

Short-term treatment of active duodenal ulcer (endoscopically or radiographically confirmed).

Maintainence of healing and reduction in recurrence of duodenal ulcer.

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions

Long-term treatment of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, multiple endocrine adenomas, systemic mastocytosis.

Gastric Ulcer

Short-term treatment of active benign gastric ulcer.

Gastroesophageal Reflux (GERD)

Short-term treatment of erosive esophagitis (endoscopically diagnosed) in patients with GERD.

Treatment of symptomatic GERD† [off-label].

Self-medication as initial therapy to achieve acid suppression, control symptoms, and prevent complications of less severe symptomatic GERD† [off-label].

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of upper GI bleeding resulting from stress-related mucosal damage (erosive esophagitis, stress ulcers) in critically ill patients.

Treatment of upper GI bleeding† [off-label] secondary to hepatic failure, esophagitis, duodenal or gastric ulcers when hemorrhage is not caused by major blood vessel erosion.

Heartburn (pyrosis), Acid Indigestion (hyperchlorhydria), or Sour Stomach

Short-term self-medication for relief of heartburn symptoms in adults and adolescents≥12 years of age.

Short-term self-medication for prevention of heartburn symptoms associated with acid indigestion (hyperchlorhydria) and sour stomach brought on by ingestion of certain foods and beverages in adults and children ≥12 years of age.

Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally, IV, or IM.

Administer by IM or slow IV injection, or by intermittent or continuous IV infusion in hospitalized patients with pathological GI hypersecretory conditions or intractable duodenal ulcer, or when oral therapy is not feasible.

Oral Administration

Administer with or without food; administration with food may delay and slightly decrease absorption, but achieves maximum antisecretory effect when stomach is no longer protected by food buffering effect. Administer oral tablets with water.

Antacids may be given as necessary for pain relief, but not at the same time.

For duodenal ulcer treatment, administration once daily at bedtime is the regimen of choice because of a high healing rate, maximal pain relief, decreased drug interaction potential, and maximal compliance.

For gastric ulcer treatment, administration once daily at bedtime is the regimen of choice because of convenience and decreased drug interaction potential.

For gastroesophageal reflux, once-daily dosing is not considered appropriate.

IM Administration

May be administered undiluted.

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

Dilution

Dilute 300 mg to 20 mL with 0.9% sodium chloride injection or other compatible IV solution before direct IV injection.

Rate of Administration

Inject over ≥5 minutes.

Intermittent IV infusion

Reconstitution

Reconstitute ADD-Vantage vials according to manufacturer’s directions.

Dilution

Dilute 300 mg in at least 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride injection or 5% dextrose injection or other compatible IV solution.

No additional dilution required for commercially available infusion solution (300 mg cimetidine in 50 mL of 0.9% sodium chloride injection).

Rate of Administration

Over 15–20 minutes.

Continuous IV Infusion

Dilution

Dilute 900 mg in 100–1000 mL of a compatible IV solution.

Rate of Administration

Over 24 hours.

Adjust rate to individual patient requirements.

Volume <250 mL: use controlled-infusion device (e.g., pump).

Dosage

Dosage of cimetidine hydrochloride expressed in terms of cimetidine.

Pediatric Patients

20–40 mg/kg daily in divided doses has been used in a limited number of children when potential benefits are thought to outweigh the possible risks.

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn Relief (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: 200 mg once or twice daily, or as directed by a clinician.

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: 200 mg once or twice daily or as directed by a clinician; administer immediately (or up to 30 minutes) before ingestion of causative food or beverage.

Adults

General Parenteral Dosage

Parenteral dosage regimens for GERD have not been established.

General parenteral dosage (in hospitalized patients with pathologic hypersecretory conditions or intractable ulcer, or for short-term use when oral therapy is not feasible):

IM

300 mg every 6–8 hours.

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

300 mg every 6–8 hours.

300 mg more frequently if increased daily dosage is necessary (i.e., single doses not >300 mg), up to 2400 mg daily.

Intermittent IV Infusion

300 mg every 6–8 hours.

300 mg more frequently if increased daily dosage is necessary (i.e., single doses not >300 mg), up to 2400 mg daily.

Continuous IV infusion

900 mg over 24 hours (37.5 mg/hour).

For more rapid increase in gastric pH, a loading dose of 150 mg may be given as an intermittent infusion before continuous infusion.

Duodenal Ulcer

Treatment of Active Duodenal Ulcer

OralDosage of choice: 800 mg once daily at bedtime.

Patients with ulcer >1 cm in diameter who are heavy smokers (i.e., ≥1 pack daily) when rapid healing (e.g., within 4 weeks) is considered important: 1.6 g daily at bedtime.

Administer for 4–6 weeks unless healing is confirmed earlier. If not healed or symptoms continue after 4 weeks, additional 2–4 weeks of full dosage therapy may be beneficial. More than 6–8 weeks at full dosage is rarely needed.

Healing of active duodenal ulcers may occur in 2 weeks in some, and occurs within 4 weeks in most patients.

Other regimens (no apparent rationale for these other than familiarity of use) that have been used: 300 mg 4 times daily with meals and at bedtime; 200 mg 3 times daily and 400 mg at bedtime; 400 mg twice daily in the morning and at bedtime.

Maintenance of Healing of Duodenal Ulcer

Oral400 mg daily at bedtime. Efficacy not increased by higher dosages or more frequent administration.

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Oral300 mg 4 times daily with meals and at bedtime.

Higher doses administered more frequently may be necessary; adjust dosage according to response and tolerance but in general, do not exceed 2400 mg daily.

Continue as long as necessary.

Continuous IV InfusionMean infused dose of 160 mg/hour (range: 40-600 mg/hour) in one study.

Gastric Ulcer

Oral

Preferred regimen: 800 mg once daily at bedtime.

Alternative regimen: 300 mg 4 times daily, with meals and at bedtime.

Monitor to ensure rapid progress to complete healing.

Studies limited to 6 weeks, efficacy for >8 weeks not established.

GERD

Once daily (at bedtime) not considered appropriate therapy.

Treatment of Symptomatic GERD† [off-label]

Oral300 mg 4 times daily has been used.

Treatment of Erosive Esophagitis

Oral800 mg twice daily or 400 mg 4 times daily (e.g., before meals and at bedtime) for up to 12 weeks.

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding

Continuous IV Infusion50 mg/hour; loading dose not required.

Safety and efficacy of therapy beyond 7 days has not been established.

Alternative dosage: Some clinicians recommend 300-mg IV loading dose over 5–20 minutes, then continuous IV infusion at 37.5–50 mg/hour; titrate with 25-mg/hour increments up to 100 mg/hour based on gastric pH (e.g., to maintain a pH of at least 3.5–4).

Intermittent IV doses may be less effective in preventing upper GI bleeding than continuous IV infusion.

Treatment of Upper GI Bleeding† [off-label]

Oral1–2 g daily in 4 divided doses has been used.

IV1–2 g daily in 4 divided doses has been used.

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn (Self-medication)

Oral200 mg once or twice daily, or as directed by clinician.

Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

Oral200 mg once or twice daily or as directed by a clinician; administer immediately (or up to 30 minutes) before ingestion of causative food or beverage.

Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn (Self-Medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralAdolescents ≥12 years of age: Maximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Adults

General Parenteral Dosage

General parenteral dosage (hospitalized patients with pathologic hypersecretory conditions or intractable duodenal ulcer, or short-term use when oral therapy is not feasible):

Direct IV injection

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Maximum 300 mg per dose.

Maximum concentration 300 mg/20 mL.

Maximum injection rate: 20 mL over not less than 5 minutes (4 mL per minute).

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Maximum 300 mg per dose.

Maximum concentration 300 mg/50 mL.

Maximum infusion rate: 15–20 minutes.

GERD

Short-term Treatment of Erosive Esophagitis

OralSafety and efficacy beyond 12 weeks of administration have not been established.

Heartburn, Acid Indigestion, or Sour Stomach

Heartburn Relief (Self-medication)

OralMaximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Prevention of Heartburn (Self-medication)

OralMaximum 400 mg in 24 hours, but not continuously for >2 weeks except under clinician supervision.

Duodenal Ulcer

Intermittent Direct IV Injecton

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Gastric Ulcer

Short-term treatment of Active Benign Gastric Ulcer

OralSafety and efficacy beyond 8 weeks have not been established.

Intermittent Direct IV InjectionMaximum 2.4 g daily.

Intermittent IV InfusionMaximum 2.4 g daily.

Pathologic GI Hypersecretory Conditions (e.g., Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome)

Oral

Maximum usually 2.4 g daily.

Intermittent Direct IV Injection

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Intermittent IV Infusion

Maximum 2.4 g daily.

Upper GI Bleeding

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding

Continuous IV InfusionSafety and efficacy beyond 7 days have not been established.

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

Severe (Clcr< 30 mL/minute)

Oral

300 mg every 12 hours.

Accumulation may occur; use lowest frequency of dosing compatible with adequate response.

Increase frequency to every 8 hours or more frequently (with caution) if required.

Presence of hepatic impairment may require further dosage reduction.

Direct IV Injection

300 mg every 12 hours.

Accumulation may occur; use lowest frequency compatible with adequate response.

Increase frequency to every 8 hours or more frequently (with caution) if required

Presence of hepatic impairment may require further dosage reduction.

Continuous IV Infusion

Prevention of Upper GI Bleeding: One-half recommended dosage (i.e., 25 mg/hour).

Hemodialysis

Decreases blood levels; administer at the end of hemodialysis and every 12 hours during interdialysis.

Hepatic Impairment

May require further dosage reduction in the presence of severe renal impairment.

Cautions for Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to cimetidine or any ingredient in the formulation.

Warnings/Precautions

General Precautions

Cardiovascular Effects

Rapid IV administration associated rarely with hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias; avoid.

Gastric Malignancy

Response to cimetidine does not preclude presence of gastric malignancy.

CNS Effects

Reversible confusional states reported, especially in geriatric (i.e., ≥50 years) and severely ill (e.g., hepatic or renal disease, organic brain syndrome) patients. Usually occurs within 2–3 days after initiating cimetidine and resolves within 3–4 days after discontinuance.

Respiratory Effects

Administration of H2-receptor antagonists has been associated with an increased risk for developing certain infections (e.g., community-acquired pneumonia).

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.

Pregnant women should consult a clinician before using for self-medication.

Lactation

Distributed into milk. Generally, do not nurse during therapy with cimetidine.

Nursing women should consult a clinician before using for self-medication.

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <16 years of age; do not use unless potential benefits outweigh risks.

Safety and efficacy for self-medication not established in children <12 years of age; do not use unless directed by a clinician.

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustments necessary in patients with severe renal impairment.

Hepatic Impairment

Further dosage adjustments may be necessary in presence of severe renal impairment.

Immunocompromised Patients

Increased possibility of Strongyloides stercoralis hyperinfection with decreased gastric acidity.

Common Adverse Effects

Headache, dizziness, somnolence, diarrhea.

With ≥1 month of therapy: gynecomastia.

With IM therapy: transient pain at injection site.

Drug Interactions

Inhibits hepatic microsomal enzyme systems, decreases hepatic metabolism of some drugs. If necessary, adjust dosage of hepatically metabolized drugs when cimetidine therapy is initiated or discontinued.

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol |

Possible increased blood alcohol concentrations, psychomotor impairment |

Potential for psychomotor impairment controversial, but use caution during performance of hazardous tasks requiring mental alertness, physical coordination |

|

Antacids |

Decreased cimetidine absorption |

Administer 1 hour before or after cimetidine in the fasting state, or 1 hour after cimetidine is taken with food. |

|

Benzodiazepines |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of certain benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, triazolam) |

Adjust dosage if needed |

|

Calcium-channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine) |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of nifedipine |

Adjust dosage if needed |

|

Ketoconazole |

Absorption of ketoconazole may be affected by altered gastric pH |

Administer ≥2 hours before cimetidine |

|

Lidocaine |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of lidocaine |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed |

|

Metronidazole |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of metronidazole |

Adjust dosage if needed |

|

Myelosuppressive drugs (e.g., alkylating agents [e.g., carmustine], antimetabolites) and/or therapies (radiation) |

May potentiate myelosuppression |

|

|

Phenytoin |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of phenytoin |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed |

|

Propranolol |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of propranolol |

Adjust dosage if needed |

|

Theophylline |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of theophylline |

Adverse effects reported, adjust dosage if needed |

|

Triamterene |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of triamterene |

Consider potential of clinically important interaction |

|

Tricyclic Antidepressants |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of certain tricyclic antidepressants |

Adjust dosage if needed |

|

Warfarin |

Potential for delayed elimination, increased blood concentrations of warfarin |

Monitor PT, adjust dosage if needed |

Cimetidine, Cimetidine Hydrochloride Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Oral: 60–70%.

Onset

≥70% decrease in basal acid secretion within 45 minutes after single 300- or 400-mg IV dose in healthy males.

Duration

|

Dosage Regimen |

Effect On Acid Secretion |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Oral: 800 mg at bedtime in duodenal ulcer patients |

Mean hourly nocturnal secretion decreased by 85% over 8 hours. |

No effect on daytime acid secretion |

|

Oral: 1600 mg at bedtime in duodenal ulcer patients |

Mean hourly nocturnal secretion decreased by 100% over 8 hours, 35% decrease for additional 5 hours. |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression |

|

Oral: 400 mg twice daily in duodenal ulcer pateints |

Nocturnal secretion decreased by 47–83% over 6–8 hours |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression |

|

Oral: 300 mg 4 times daily in duodenal ulcer patients |

Nocturnal secretion decreased by 54% over 9 hours |

Moderate (<60%) 24-hour suppression |

|

Oral: Single 300-mg dose within 1 hour after meal in duodenal ulcer patients |

Food-stimulated secretion decreased by 50% for 1 hour, then 75% for 2 hours. |

|

|

Oral: 300-mg dose at breakfast in duodenal ulcer patients |

Continued suppression for 4 hours, with partial suppression after lunch |

Effect enhanced and maintained by additional 300-mg dose with lunch |

|

Oral: 300-mg dose with food |

Mean gastric pH 3.5–4 at 1 hour, 5.5–6.1 at 4 hours |

|

|

Oral: Single dose 300 mg with food |

Mean gastric pH: 3.5, 3.1, 3.8, 6.1 at hour 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively |

Placebo mean gastric pH: 2.6, 1.6, 1.9, 2.2 at hour 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively |

|

Oral: 300–400 mg in fasting state in duodenal ulcer patients |

Anacidity for up to 8 hours |

|

|

Oral: 300 mg in duodenal ulcer patients |

Basal gastric acid output decreased by 90% for 4 hours |

Meal-stimulated acid secretion by 66% for 3 hours |

|

IV continuous infusion: mean dosage of 160 mg/hour (range:40-600 mg/hour) in pathologic hypersecretory conditions |

Maintained secretion at ≤10 mEq/hour |

|

|

IV continuous infusion (37.5 mg/hour or 900 mg daily) in patients with active or healed duodenal or gastric ulcer |

Maintained gastric pH at >4 for >50% of the time at steady-state. |

|

|

Intermittent injection: (300 mg every 6 hours or 1200 mg daily) in patients with active or healed duodenal or gastric ulcer |

Maintained gastric pH at >4 for >50% of the time at steady-state. |

|

|

IV: Single 300- or 400-mg dose in healthy males |

≥70% decrease in basal acid secretion maintained for 4–4.5 hours |

Food

Delays, slightly decreases absorption. However, administration with meals achieves maximum blood concentrations and antisecretory effect when stomach is no longer protected by food buffering effect.

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed throughout the body.

Distributed into human milk.

Crosses the placenta in animals.

Plasma Protein Binding

15–20%.

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized to sulfoxide (major metabolite) and 5-hydroxymethyl derivatives in liver. More extensively metabolized after oral than parenteral administration.

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in urine. Single oral dose: 48% (unchanged) excreted in urine over 24 hours. IV or IM: about 75% (unchanged) excreted in urine within 24 hours. Single IV dose of radiolabeled cimetidine: 80–90% (50–73% unchanged, remainder as metabolites) excreted in urine over 24 hours. About 10% excreted in feces.

Half-life

2 hours.

After IV administration in children 4.1–15 years of age: Apparent biphasic decline of plasma cimetidine and cimetidine sulfoxide concentrations with half-lives of 1.4 and 2.6 hours, respectively.

Special Populations

2.9 hours in patients with Clcr 20–50 mL/minute. 3.7 hours in patients with Clcr <20 mL/minute. 5 hours in anephric patients.

Stability

Storage

Oral

Liquid and Tablets

Tight, light-resistant containers at 15–30°C.

Parenteral

Injection

15–30°C. Protect from light. Do not refrigerate. Stable in most IV solutions for at least 3 days at room temperature in concentrations of 1.2–5 mg/mL, but use within 48 hours when diluted as directed.

Injection for IV infusion only

15–30°C. Protect from excessive heat; brief exposure up to 40°C does not adversely affect stability. Stable through the labeled expiration date when stored as recommended.

Actions

-

Inhibits basal and stimulated gastric acid secretion.

-

Competitively inhibits histamine at parietal cell H2 receptors.

-

Weak antiandrogenic effect.

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of patients informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.

-

Importance of taking antacids on an empty stomach 1 hour before or 1 hour after oral administration of cimetidine, or 1 hour after the drug is taken with food, but not at same time as oral cimetidine.

-

Importance of women informing clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.

-

Before self-medication, importance of consulting clinician if taking warfarin, theophylline, or phenytoin.

-

Importance of following dosage instructions when cimetidine is administered for self-medication, unless otherwise directed by a clinician.

-

Importance of promptly informing clinician of persistent abdominal pain or difficulty swallowing.

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Solution |

300 mg/mL* |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride Oral Solution |

Actavis |

|

Tagamet (with parabens, povidone, and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

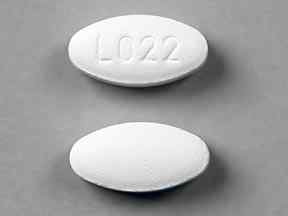

Tablets, film-coated |

200 mg* |

Tagamet HB 200 |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|

|

Tagamet HB (with povidone) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|||

|

300 mg* |

Tagamet (with povidone and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

||

|

400 mg* |

Tagamet Tiltab (with povidone and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

||

|

800 mg* |

Tagamet Tiltab (with povidone and propylene glycol; scored) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Solution |

300 mg (of cimetidine) per 5 mL* |

Tagamet HCl (with alcohol 2.8% parabens and propylene glycol) |

GlaxoSmithKline |

|

Parenteral |

Injection |

150 mg (of cimetidine) per mL |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride Injection |

Endo |

|

Injection, for IV infusion only |

150 mg (of cimetidine) per mL |

Cimetidine Hydrochloride ADD-Vantage |

Hospira |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

Injection, for IV infusion only |

6 mg (of cimetidine) per mL (300, 900, or 1200 mg) in 0.9% Sodium Chloride |

Cimetidine HCl in 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection (available in flexible plastic container) |

Hospira |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions October 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

Reload page with references included

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

More about cimetidine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (22)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: H2 antagonists

- Breastfeeding

- En español