Metronidazole (Monograph)

Brand name: Flagyl

Drug class: Nitroimidazole Derivatives, Miscellaneous

- Antiprotozoal Agents

Warning

Introduction

Antibacterial and antiprotozoal;.152 197 430 494 495 nitroimidazole derivative.494

Uses for Metronidazole

Bone and Joint Infections

Adjunct for treatment of bone and joint infections caused by Bacteroides, including the B. fragilis group (B. fragilis, B. distasonis, B. ovatus, B. thetaiotaomicron, B. vulgatus).152 197 495

Endocarditis

Treatment of endocarditis caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group).152 197 495

Gynecologic Infections

Treatment of gynecologic infections (including endometritis, endomyometritis, tubo-ovarian abscess, postsurgical vaginal cuff infection) caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group), Clostridium, Peptococcus niger, or Peptostreptococcus.152 197 495

Treatment of acute pelvic inflammatory disease (PID); used in conjunction with other anti-infectives.199 341 496 Metronidazole is included in PID regimens to provide coverage against anaerobes.341

When a parenteral regimen is indicated for PID, an initial regimen of IV cefoxitin and IV or oral doxycycline is recommended followed by oral doxycycline; if tubo-ovarian abscess is present, some experts recommend that the oral follow-up regimen include metronidazole (or clindamycin) in addition to doxycycline.341

When an oral regimen is indicated for PID, an single IM dose of ceftriaxone, cefoxitin (with oral probenecid), or cefotaxime is recommended in conjunction with oral doxycycline (with or without oral metronidazole).199 341 496 Alternatively, if a parenteral cephalosporin is not feasible and the community prevalence and individual risk for gonorrhea is low, a regimen of oral levofloxacin or oral ofloxacin (with or without oral metronidazole) may be considered.496

Intra-abdominal Infections

Treatment of intra-abdominal infections (including peritonitis, intra-abdominal abscess, liver abscess) caused by susceptible Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group), Clostrium, Eubacterium, P. niger, or Peptostreptococcus.152 197 495

Meningitis and Other CNS Infections

Treatment of CNS infections (including meningitis, brain abscess) caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group).152 197 495

Respiratory Tract Infections

Treatment of respiratory tract infections (including pneumonia) caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group).152 197 495

Septicemia

Treatment of septicemia caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group) or Clostridium.152 197 495

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

Treatment of skin and skin structure infections caused by Bacteroides (including the B. fragilis group), Clostridium, Fusobacterium, P. niger, or Peptostreptococcus.152 197 495

Amebiasis

Treatment of acute intestinal amebiasis and amebic liver abscess caused by Entamoeba histolytica.100 152 153 197 364 368 370 Oral metronidazole or oral tinidazole followed by a luminal amebicide (iodoquinol, paromomycin) is the regimen of choice for mild to moderate or severe intestinal disease and for amebic hepatic abscess.100 153 364 368 370

Bacterial Vaginosis

Treatment of bacterial vaginosis (formerly called Haemophilus vaginitis, Gardnerella vaginitis, nonspecific vaginitis, Corynebacterium vaginitis, or anaerobic vaginosis) in pregnant or nonpregnant women.199 292 297 298 302 341 365 366 430

CDC recommends treatment of bacterial vaginosis in all symptomatic women (including pregnant women).341 In addition, asymptomatic pregnant women at high risk for complications of pregnancy should be screened (preferably at the first prenatal visit) and treatment initiated if needed.341

Treatment recommendations for bacterial vaginosis in HIV-infected women are the same as those for women without HIV infection.341

Regimens of choice in nonpregnant women are a 7-day regimen of oral metronidazole, a 5-day regimen of intravaginal metronidazole gel, or a 7-day regimen of intravaginal clindamycin cream;341 alternative regimens are a 7-day regimen of oral clindamycin or 3-day regimen of intravaginal clindamycin suppositories.341 The preferred regimens for pregnant women are a 7-day regimen of oral metronidazole or a 7-day regimen of oral clindamycin.341

Regardless of regimen used, relapse or recurrence is common;287 295 297 298 300 302 307 341 365 an alternative regimen (e.g., topical therapy when oral therapy was used initially) may be used in such situations.297 341

Routine treatment of asymptomatic male sexual contacts of women who have relapsing or recurrent bacterial vaginosis not recommended.341

Balantidiasis

Alternative to tetracycline for treatment of balantidiasis† [off-label] caused by Balantidium coli.100 153

Blastocystis hominis Infections

Treatment of infections caused by Blastocystis hominis † [off-label].100 153 368 371 372 May be effective, but metronidazole resistance may be common.153

Clinical importance of B. hominis as a cause of GI pathology is controversial;100 153 368 371 372 unclear when treatment is indicated.100 368 371 Some clinicians suggest treatment be reserved for certain individuals (e.g., immunocompromised patients) when symptoms persist and no other pathogen or process is found to explain their GI symptoms.100 368

Clostridium difficile-associated Diarrhea and Colitis

Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis† [off-label] (CDAD; also known as antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis, C. difficile diarrhea, C. difficile colitis, and pseudomembranous colitis).100 125 126 127 128 129 131 132 312 313 314 315 316 344 345 443 444 445 446 447

Drugs of choice are metronidazole and vancomycin; 100 312 313 314 315 316 metronidazole generally preferred and vancomycin reserved for those with severe or potentially life-threatening colitis, patients in whom metronidazole-resistant C. difficile is suspected, patients in whom metronidazole is contraindicated or not tolerated, or those who do not respond to metronidazole.100 126 127 312 313 314 315 316 322 323 406 443 444 445 446 447 448

Crohn’s Disease

Mangement of Crohn’s disease† [off-label] as an adjunct to conventional therapies.101 102 103 104

Has been used with467 468 471 475 476 477 485 or without ciprofloxacin;101 102 103 104 105 469 470 471 472 473 474 478 479 484 485 486 for induction of remission of mildly to moderately active Crohn’s disease† [off-label].101 102 103 104 105 467 468 469 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 484

Has been used for refractory perianal Crohn’s disease†.102 104 105 470 471 474 478 479 485 486

Dientamoeba fragilis Infections

Treatment of infections caused by Dientamoeba fragilis †.153 Drugs of choice are iodoquinol, paromomycin, tetracycline, or metronidazole.153

Dracunculiasis

Treatment of dracunculiasis† caused by Dracunculus medinensis (guinea worm disease).153

Treatment of choice is slow extraction of worm combined with wound care.153 Metronidazole is not curative, but decreases inflammation and facilitates worm removal.153

Giardiasis

Treatment of giardiasis†.100 153 367 452 Drugs of choice are metronidazole, tinidazole, or nitazoxanide;100 153 367 452 alternatives are paromomycin, furazolidone (no longer commercially available in the US), or quinacrine (not commercially available in the US).100 153 367

Treatment of asymptomatic carriers of giardiasis†.100 367 Treatment of such carriers not generally recommended, except possibly in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia or cystic fibrosis or in an attempt to prevent household transmission of the disease from toddlers to pregnant women.100

Helicobacter pylori Infection and Duodenal Ulcer Disease

Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection and duodenal ulcer disease (active or a history of duodenal ulcer); eradication of H. pylori has been shown to reduce the risk of duodenal ulcer recurrence.

Used in a multiple-drug regimen that includes metronidazole, tetracycline, and bismuth subsalicylate and a histamine H2-receptor antagonist.455 If initial 14-day regimen does not eradicate H. pylori, a retreatment regimen that does not include metronidazole should be used.455

Nongonococcal Urethritis

Treatment of recurrent and persistent urethritis† in patients with nongonococcal urethritis who have already been treated with a recommended regimen (i.e., azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, ofloxacin or levofloxacin).341

Oral metronidazole or oral tinidazole used in conjunction with oral azithromycin (if azithromycin was not used in the initial regimen) is the regimen recommended by CDC for recurrent and persistent urethritis in patients who were compliant with their initial regimen and have not been re-exposed.341

Rosacea

Treatment of inflammatory lesions (papules and pustules) and erythema associated with rosacea† (acne rosacea).137 139 145 146 148 168 180 181 Topical metronidazole may be preferred to oral metronidazole.137 181

Tetanus

Adjunct in treatment of tetanus caused by C. tetani.100 489

Trichomoniasis

Treatment of symptomatic and asymptomatic trichomoniasis when Trichomonas vaginalis has been demonstrated by an appropriate diagnostic procedure (e.g., wet smear and/or culture, OSOM Trichomonas Rapid Test, Affirm VP III).100 152 153 197 199 297 298 302 337 338 339 341

Drug of choice is metronidazole or tinidazole.100 153 199 297 302 337 338 339 341 Goal of treatment is to provide symptomatic relief, achieve microbiologic cure, and reduce transmission; to achieve this goal, both the index patient and sexual (particularly steady) partner(s) should be treated.153 199 297 302 339 341

If treatment failure occurs with initial metronidazole treatment and reinfection is excluded, alternative regimens using metronidazole or tinidazole can be used.153 199 341 If retreatment is ineffective, consultation with an expert (available through CDC) is recommended.341

Perioperative Prophylaxis

Perioperative prophylaxis to reduce the incidence of postoperative anaerobic bacterial infections in patients undergoing colorectal surgery.109 110 111 112 156 495 Preferred regimens are IV cefoxitin alone; IV cefazolin and IV metronidazole; oral erythromycin and oral neomycin; or oral metronidazole and oral neomycin.110 112 490

Perioperative prophylaxis in patients undergoing appendectomy†;109 111 110 112 113 used in conjunction with cefazolin.110 Preferred regimens for appendectomy (nonperforated) are IV cefoxitin alone or IV cefazolin and IV metronidazole.110

Prophylaxis in Sexual Assault Victims

Empiric anti-infective prophylaxis in sexual assault victims†; used in conjunction with IM ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin or doxycycline.199 341

Metronidazole Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally152 197 430 or by continuous or intermittent IV infusion.156 495 Do not administer by rapid IV injection because of the low pH of the reconstituted product.156 495

In the treatment of serious anaerobic infections, parenteral route usually is used initially and oral metronidazole substituted when warranted by patient’s condition.152 197

Oral Administration

Administer extended-release tablets at least 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals.430

Extemporaneously Compounded Oral Liquid

An extemporaneously compounded oral liquid formulation of metronidazole containing 50 mg/mL has been prepared.98

Standardize 4 Safety

Standardized concentrations for an extemporaneously compounded oral liquid formulation of metronidazole have been established through Standardize 4 Safety (S4S), a national patient safety initiative to reduce medication errors, especially during transitions of care.99 Because recommendations from the S4S panels may differ from the manufacturer’s prescribing information, caution is advised when using concentrations that differ from labeling, particularly when using rate information from the label.99 For additional information on S4S (including updates that may be available), see [Web].99

|

Concentration Standards |

|---|

|

50 mg/mL |

IV Infusion

Commercially available metronidazole injection for IV infusion does not need to be diluted or neutralized prior to IV administration.156 495

Metronidazole hydrochloride powder for injection must by reconstituted, diluted, and then neutralized prior to IV administration.156

Reconstitution and Dilution

Reconstitute metronidazole hydrochloride powder for injection by adding 4.4 mL of sterile or bacteriostatic water for injection, 0.9% sodium chloride injection, or bacteriostatic sodium chloride injection to the vial containing 500 mg of metronidazole.156 The reconstituted solution contains approximately 100 mg of metronidazole/mL and has a pH of 0.5–2.156

The reconstituted metronidazole hydrochloride solution must be further diluted with 0.9% sodium chloride injection, 5% dextrose injection, or lactated Ringer’s injection to a concentration of ≤8 mg/mL.156

The reconstituted and diluted metronidazole hydrochloride solution must then be neutralized by adding approximately 5 mEq of sodium bicarbonate injection for each 500 mg of metronidazole.156 The addition of sodium bicarbonate to the metronidazole hydrochloride solution may generate carbon dioxide gas and it may be necessary to relieve gas pressure in the container.156

Rate of Administration

IV infusions usually are infused over 1 hour.156 495

Dosage

Available as metronidazole152 156 197 430 495 and metronidazole hydrochloride;156 dosage expressed in terms of metronidazole.156

Pediatric Patients

General Dosage in Neonates†

Oral or IV

Neonates <1 week of age: AAP recommends 7.5 mg/kg every 24–48 hours in those weighing <1.2 kg, 7.5 mg/kg every 24 hours in those weighing 1.2–2 kg, or 7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours in those weighing >2 kg.100

Neonates 1–4 weeks of age: AAP recommends 7.5 mg/kg every 24–48 hours in those weighing <1.2 kg, 7.5 mg/kg every 12 hours in those weighing 1.2–2 kg, and 15 mg/kg every 12 hours in those weighing >2 kg.100

General Dosage in Children ≥1 Month of Age†

Oral

15–35 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses.100 AAP states oral route inappropriate for severe infections.100

Amebiasis

Entamoeba histolytica Infections

Oral35–50 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 7–10 (usually 10) days;152 153 197 370 follow-up with a luminal amebicide (e.g., iodoquinol, paromomycin).153

Bacterial Vaginosis†

Oral

Children weighing <45 kg: 15 mg/kg daily (up to 1 g) in 2 divided doses given for 7 days.100

Adolescents: 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.100

Balantidiasis†

Oral

35–50 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 5 days.153

Blastocystis hominis Infections†

Oral

20–35 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 10 days may improve symptoms in some patients.100

Crohn’s Disease†

Oral

10–20 mg/kg daily (up to 1 g daily) has been recommended for children with mild perianal Crohn’s disease† or those intolerant to sulfasalazine or mesalamine.487

Clostridium difficile-associated Diarrhea and Colitis†

Oral

30–50 mg/kg daily in 3 or 4 equally divided doses given for 7–10 days (not to exceed adult dosage).100 445 446

Dientamoeba fragilis Infections†

Oral

20–40 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 10 days.153

Dracunculiasis†

Oral

25 mg/kg daily (up to 750 mg) in 3 divided doses given for 10 days.153 Is not curative, but may decrease inflammation and facilitate worm removal.153

Giardiasis†

Oral

15 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 5–7 days.153 367 452

Nongonococcal Urethritis†

Oral

Recurrent or persistent urethritis in adolescents: A single 2-g dose given in conjunction with a single 1-g dose of oral azithromycin (if azithromycin not used in the initial regimen).341

Tetanus†

Oral

30 mg/kg daily (up to 4 g daily) in 4 doses given for 10–14 days.100

IV

30 mg/kg daily (up to 4 g daily) in 4 doses given for 10–14 days.100

Trichomoniasis†

Oral

Prepubertal children weighing <45 kg: 15 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses (up to 2 g daily) given for 7 days.100 153

Adolescents: A single 2-g dose or 500 mg twice daily for 7 days.100

Prophylaxis in Sexual Assault Victims†

Oral

Preadolescent children weighing <45 kg: 15 mg/kg daily given in 3 divided doses for 7 days given in conjunction with IM ceftriaxone and either oral azithromycin or oral erythromycin.100 341

Adolescents and preadolescent children weighing ≥45 kg: A single 2-g dose given in conjunction with IM ceftriaxone and either oral azithromycin or oral doxycycline.100 341

Adults

Anaerobic Bacterial Infections

Serious Infections

Oral7.5 mg/kg every 6 hours (up to 4 g daily).152 156 197

IV, then OralAn initial IV loading dose of 15 mg/kg followed by IV maintenance doses of 7.5 mg/kg every 6 hours.156 495 After clinical improvement occurs, switch to oral metronidazole (7.5 mg/kg every 6 hours).156 495

Total duration of treatment usually is 7–10 days, but infections of bone and joints, lower respiratory tract, or endocardium may require longer treatment.156 495

Gynecologic Infections

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Oral500 mg twice daily given for 14 days; used in conjunction with a single IM dose of ceftriaxone (250 mg), cefoxitin (2 g with oral probenecid 1 g), or another parenteral cephalosporin (e.g., cefotaxime) and 14-day regimen of oral doxycycline (100 mg twice daily).341 496

Alternatively, 500 mg twice daily given for 14 days; used in conjunction with a 14-day regimen of oral ofloxacin (400 mg twice daily) or levofloxacin (500 mg once daily).199 341 496 Regimens containing a fluoroquinolone should only be considered when a parenteral cephalosporin is not feasible and the community prevalence and individual risk of gonorrhea is low.496

Amebiasis

Entamoeba histolytica Infections

Oral750 mg 3 times daily given for 5–10 (usually 10) days for intestinal amebiasis152 153 197 364 368 370 or 500–750 mg 3 times daily given for 5–10 (usually 10) days for amebic liver abscess.152 197 364 368 370 Alternatively, amebic liver abscess has been treated with 2.4 g once daily given for 1 or 2 days.364

Follow-up with a luminal amebicide (e.g., iodoquinol, paromomycin) after metronidazole.153 364 368 370

IV500 mg every 6 hours for 10 days.364

Bacterial Vaginosis

Nonpregnant Women

OralConventional tablets: 500 mg twice daily given for 7 days.100 199 286 297 298 300 301 302 341 366 A single 2-g dose has been used (e.g., for patients who may be noncompliant with the multiple-dose regimen),120 122 199 292 297 but appears to be less effective than other regimens and is no longer recommended by CDC.341

Extended-release tablets: 750 mg once daily given for 7 days.199 341 416 417 430

Pregnant Women

OralConventional tablets: 500 mg twice daily or 250 mg 3 times daily given for 7 days.341 416 417

Contraindicated during first trimester of pregnancy.152 197 430 In addition, single-dose regimens not recommended in pregnant women because of the slightly higher serum concentrations attained, which may reach fetal circulation.152

Balantidiasis†

Oral

750 mg 3 times daily given for 5 days.153

Blastocystis hominis Infections†

Oral

750 mg 3 times daily given for 10 days may improve symptoms in some patients.100 153

Crohn’s Disease†

Oral

400 mg twice daily101 103 105 or 1 g daily has been effective for treatment of active Crohn’s disease†.467 472 473 475 476 482 For treatment of refractory perineal disease, 20 mg/kg (1–1.5 g) given in 3–5 divided doses daily has been employed.102 103 104 105 478 486

Clostridium difficile-associated Diarrhea and Colitis†

Oral

750 mg to 2 g daily in 3 or 4 divided doses given for 7–14 days.125 126 129 131 132 133 313 314

Dose-ranging studies to determine comparative efficacy have not been performed; most commonly employed regimens are 250 mg 4 times daily or 500 mg 3 times daily given for 10 days.443 444 445 446

IV

500–750 mg every 6–8 hours; use when oral therapy is not feasible.134 161 162 313 342 343 445

Dientamoeba fragilis Infections†

Oral

500–750 mg 3 times daily given for 10 days.153

Dracunculiasis†

Oral

250 mg 3 times daily given for 10 days.153 Is not curative, but may decrease inflammation and facilitate worm removal.153

Giardiasis†

Oral

250 mg 3 times daily given for 5–7 days.153 367 452

Helicobacter pylori Infection and Duodenal Ulcer Disease

Oral

250 mg in conjunction with tetracycline (500 mg) and bismuth subsalicylate (525 mg) 4 times daily (at meals and at bedtime) for 14 days; these drugs should be given concomitantly with an H2-receptor antagonist in recommended dosage.455

Nongonococcal Urethritis†

Oral

Recurrent or persistent urethritis: A single 2-g dose given in conjunction with a single 1-g dose of oral azithromycin (if azithromycin not used in the initial regimen).341

Tetanus†

IV

500 mg every 6 hours given for 7–10 days.489

Trichomoniasis

Initial Treatment

Oral2 g as a single dose152 153 199 341 or in 2 divided doses.152 Alternatively, 500 mg twice daily given for 7 days153 199 341 or 375 mg twice daily given for 7 days.199 197 Manufacturer also recommends 250 mg 3 times daily given for 7 days.152

Retreatment

Oral500 mg twice daily given for 7 days.297 341 If repeated failure occurs, CDC recommends 2 g once daily given for 5 days.297 341 Others recommend retreatment with 2–4 g daily for 7–14 days if metronidazole-resistant strains are involved.153 199

Do not administer repeat courses of treatment unless presence of T. vaginalis is confirmed by wet smear and/or culture and an interval of 4–6 weeks has passed since the initial course.152 197

If treatment of resistant infection is guided by in vitro susceptibility testing under aerobic conditions, some clinicians recommend that T. vaginalis strains exhibiting low-level resistance (minimum lethal concentration [MLC] <100 mcg/mL) be treated with 2 g daily for 3–5 days, those with moderate (intermediate) resistance (MLC 100–200 mcg/mL) be treated with 2–2.5 g daily for 7–10 days, and those with high-level resistance (MLC >200 mcg/mL) be treated with 3–3.5 g daily for 14–21 days.124 302 338 340 Because strains with high-level resistance are difficult to treat,124 297 302 338 340 CDC recommends that patients with culture-documented infection who do not respond to repeat regimens at dosages up to 2 g daily for 3–5 days and in whom the possibility of reinfection has been excluded should be managed in consultation with an expert (available through CDC).297 341

Perioperative Prophylaxis

Colorectal Surgery

IV0.5 g given at induction of anesthesia (within 0.5–1 hour prior to incision); used in conjunction with IV cefazolin (1–2 g).110

Manufacturer recommends 15 mg/kg by IV infusion over 30–60 minutes 1 hour prior to the procedure and, if necessary, 7.5 mg/kg by IV infusion over 30–60 minutes at 6 and 12 hours after the initial dose.156 495 The initial preoperative dose must be completely infused approximately 1 hour prior to surgery to ensure adequate serum and tissue concentrations of metronidazole at the time of incision.156 495 Prophylactic use of metronidazole should be limited to the day of surgery and should not be continued for more than 12 hours after surgery.156 495

Oral2 g with oral neomycin sulfate (2 g) given at 7 p.m. and 11 p.m. on day before surgery; used in conjunction with appropriate diet and catharsis.110

Prophylaxis in Sexual Assault Victims†

Oral

A single 2-g dose given in conjunction with IM ceftriaxone and either oral azithromycin or oral doxycycline.100 341

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Decrease dosage in patients with severe hepatic impairment and monitor plasma concentrations of the drug.152 156 160 197 430 495

Geriatric Patients

Select dosage with caution because of age-related decreases in hepatic function.152 197 430

Cautions for Metronidazole

Contraindications

-

Hypersensitivity to metronidazole or other nitroimidazole derivatives.152 156 197 430 495 Cautious desensitization has been used in some situations when use of metronidazole was considered necessary.341 436 (See Hypersensitivity Reactions and Desensitization under Cautions.)

-

Helidac Therapy (kit containing tetracycline, metronidazole, bismuth subsalicylate) contraindicated in pregnant or nursing women, pediatric patients, patients with hepatic or renal impairment, patients with known allergy to aspirin or salicylates, and those with known hypersensitivity to any component of the kit.455

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Seizures and Peripheral Neuropathy

Seizures and peripheral neuropathy (characterized by numbness or paresthesia of an extremity) reported with metronidazole.152 156 197 430 495

Persistent peripheral neuropathy reported in some patients receiving prolonged therapy.430 If abnormal neurologic signs develop, promptly discontinue drug..152 156 197 430

Use with caution in those with CNS diseases.152 197 430

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions and Desensitization

Hypersensitivity reactions, including urticaria, pruritus, erythematous rash, flushing, nasal congestion, fever, and fleeting joint pains sometimes resembling serum sickness, have been reported with metronidazole.152 156 197 430 495

Because there are no effective alternatives to metronidazole in the US for treatment of trichomoniasis, CDC states that desensitization can be attempted in patients with metronidazole hypersensitivity.341 The possibility that desensitization may be hazardous should be considered435 and adequate procedures (e.g., established IV access, BP monitoring) and therapies (e.g., epinephrine, corticosteroids, antihistamines, oxygen) for management of an acute hypersensitivity reaction should be readily available.435 Pretreatment (e.g., with an antihistamine and/or corticosteroid) also should be considered.435

Desensitization has been performed by administering increasing doses of IV metronidazole incrementally until a therapeutic dose was achieved, at which time oral dosing was initiated.435 In this regimen, an initial 5-mcg dose of IV metronidazole was given and the dose increased at 15- to 20-minute intervals to 15, 50, 150, and 500 mcg and then to 1.5, 5, 15, 30, 60, and 125 mg.435 After the 125-mg IV dose, dosing was switched to oral metronidazole and doses of 250, 500, and 2 g were given at 1-hour intervals.435 For trichomoniasis, desensitization dosing can be stopped after the 2-g dose.435 Patient should be monitored for ≥4 hours after the last dose (24 hours if there was any evidence of a reaction).435

General Precautions

Selection and Use of Anti-infectives

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of metronidazole and other antibacterials, use only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.152 197 430 495

When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, use results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing.152 197 430 495 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.152 197 430 495

Surgical procedures should be performed in conjunction with metronidazole therapy when indicated.152 156 197 430 495

In mixed aerobic and anaerobic infections, anti-infectives appropriate for treatment of aerobic bacteria should be used in conjunction with metronidazole.152 156 197 430 495

History of Blood Dyscrasia

Use with caution in patients with evidence or history of blood dyscrasias.152 156 197 430 495

Mild leukopenia has been reported, but persistent hematologic abnormalities do not occur.152 156 197 430 495

Perform total and differential leukocyte counts before and after metronidazole treatment, especially when repeated courses are necessary.152 156 197 430 495

Sodium Content

Metronidazole injection contains approximately 28 mEq of sodium per g of metronidazole.156 495 Use with caution in patients receiving corticosteroids and in those predisposed to edema.156 495

Candidiasis

Known or previously unrecognized candidiasis may present more prominent symptoms during metronidazole therapy; treatment with an appropriate antifungal is required.152 156 197 430 495

Helidac Therapy

When the kit containing tetracycline, metronidazole, and bismuth subsalicylate (Helidac Therapy) is used for the treatment of H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer disease, the cautions, precautions, and contraindications associated with tetracycline and bismuth subsalicylate must be considered in addition to those associated with metronidazole.455

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category B.152 156 197 430 495 Contraindicated during the first trimester of pregnancy.100 152 197 341 430 442

Lactation

Distributed into milk;152 156 197 430 495 discontinue nursing or the drug.152 156 197 430 495

If a single 2-g dose of metronidazole is indicated in the mother, AAP states that breast-feeding should be interrupted for 12–24 hours following the dose.100

Pediatric Use

Except for oral treatment of amebiasis, safety and efficacy not established in pediatric patients.152 156 197 430 495

Metronidazole has been used and is recommended for use in pediatric patients for various indications other than amebiasis (e.g., trichomoniasis, giardiasis).100 153 Unusual adverse effects have not been reported in pediatric patients.100

Safety and efficacy of the kit containing metronidazole, tetracycline, and bismuth subsalicylate (Helidac Therapy) for treatment of H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer disease have not been established in pediatric patients.455

Geriatric Use

Because of age-related decreases in hepatic function, monitor serum metronidazole concentrations and adjust dosage accordingly.152 197 430

Insufficient experience in those ≥65 years of age to determine whether they respond differently than younger adults to concomitant use of metronidazole, tetracycline, and bismuth subsalicylate (Helidac Therapy) for treatment of H. pylori infection and duodenal ulcer disease.455 Age-related decreases in hepatic, renal, and/or cardiac function and concomitant disease and drug therapy should be considered.455

Hepatic Impairment

Patients with severe hepatic impairment metabolize metronidazole more slowly, and increased concentrations of the drug and metabolites may occur.152 156 197 430 495

Use with caution, monitor plasma metronidazole concentrations, and reduce dosage in patients with severe hepatic impairment.152 156 197 430 495

Common Adverse Effects

Nausea, headache, anorexia, dry mouth, unpleasant metallic taste.152 156 197 430 495

Drug Interactions

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol |

Mild disulfiram-like reactions (flushing, headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, sweating) may occur if alcohol is ingested while receiving metronidazole139 152 156 157 187 196 197 430 495 |

Alcohol should not be consumed during or for at least 1 day following completion of metronidazole therapy (at least 3 days after oral capsules or extended-release tablets)152 156 197 430 495 |

|

Anticoagulants, oral (warfarin) |

Monitor PT and adjust anticoagulant dosage as needed191 192 193 194 195 |

|

|

Cimetidine |

Possible prolonged half-life and decreased clearance of metronidazole106 152 156 197 430 495 |

If used concomitantly, consider possibility of increased metronidazole adverse effects106 |

|

Disulfiram |

Acute psychoses and confusion with concomitant use152 156 197 430 495 |

Avoid concomitant use; do not initiate metronidazole therapy until 2 weeks after discontinuance of disulfiram152 156 197 430 495 |

|

Lithium |

Increased lithium concentrations resulting in lithium toxicity;151 152 155 197 430 495 renal toxicity (elevated serum creatinine, hypernatremia, abnormally dilute urine) reported151 |

Use concomitantly with caution; monitor serum lithium and creatinine concentrations during concomitant use151 152 155 197 430 495 |

|

Phenobarbital |

Decreased serum half-life and increased metabolism of metronidazole116 117 152 197 430 495 |

|

|

Phenytoin |

Decrased serum concentration and increased metabolism of metronidazole; decreased clearance of phenytoin152 156 197 430 495 |

Metronidazole Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

≥80% of an oral dose is absorbed from the GI tract.g Following oral administration of conventional tablets or capsules, peak plasma concentrations of unchanged drug and active metabolites attained within 1–3 hours.g

Following oral administration of metronidazole extended-release tablets for 7 consecutive days under fasting conditions, steady-state peak plasma concentrations attained an average of 6.8 hours after the dose.430

Food

Conventional tablets or capsules: Food decreases the rate of absorption and peak plasma concentrations; total amount of drug not affected.g

Extended-release tablets: Food increases rate of absorption and peak plasma concentrations.430

Distribution

Extent

Widely distributed into most body tissues and fluids, including bone, bile, saliva, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, vaginal secretions, seminal fluid, and cerebral and hepatic abscesses.g

Distributed into CSF; CSF concentrations are 43% of concurrent plasma concentrations in patients with uninflamed meninges and equal to or greater than concurrent plasma concentrations in patients with inflamed meninges.g

Readily crosses the placenta and is distributed into milk.g

Plasma Protein Binding

<20%.g

Elimination

Metabolism

Approximately 30–60% of an oral or IV dose is metabolized in the liver by hydroxylation, side-chain oxidation, and glucuronide conjugation.g The major metabolite, 2-hydroxy metronidazole, has some antibacterial and antiprotozoal activity.g

Elimination Route

Metronidazole and its metabolites are excreted principally in urine (60–80%) and to a lesser extent in feces (6–15%).152 197 430 g

Half-life

Adults with normal renal and hepatic function: 6–8 hours.430 g

Special Populations

Half-life may be prolonged in patients with impaired hepatic function.g In adults with alcoholic liver disease and impaired hepatic function, half-life averages 18.3 hours.160

Pharmacokinetics not affected by renal impairment.430 g

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

15–25°C.197 Dispense in well-closed container with child-resistant closure.197

Tablets

Conventional tablets: <25°C.152

Extended-release tablets: 25°C (may be exposed to 15–30°C).430 Dispense in well-closed container with child-resistant closure.430

Metronidazole Combinations

Kit containing tetracycline, metronidazole, and bismuth subsalicylate: 20–25°C.455

Parenteral

Injection for IV infusion

15–30°C; protect from light.156 495 Do not refrigerate.156

Powder for IV infusion

<25°C; protect from light.156 After reconstitution, dilution, and neutralization, use within 24 hours; do not refrigerate.156

Actions and Spectrum

-

Bactericidal, amebicidal, and trichomonacidal in action.g

-

Un-ionized at physiologic pH and readily taken up by anaerobic organisms or cells.g In susceptible organisms or cells, metronidazole is reduced by low-redox-potential electron transport proteins (e.g., nitroreductases such as ferredoxin); the reduction product(s) apparently are responsible for the cytotoxic and antimicrobial effects of the drug (e.g., disruption of DNA, inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis).g

-

Has direct anti-inflammatory effects137 139 148 166 167 and effects on neutrophil motility, lymphocyte transformation, and some aspects of cell-mediated immunity.148 168 169 170 171 172

-

Spectrum of activity includes most obligately anaerobic bacteria and many protozoa.g Inactive against fungi and viruses and most aerobic or facultatively anaerobic bacteria.g

-

Gram-positive anaerobes: Clostridium,148 152 156 164 174 176 C. difficile,175 176 C. perfringens,164 176 Eubacterium,148 152 156 164 174 175 Peptococcus,148 152 156 164 174 175 176 and Peptostreptococcus.148 152 156 164 174 176 177 275 278

-

Gram-negative anaerobes: Active against Bacteroides fragilis,148 152 156 164 173 174 175 176 275 277 280 B. distasonis,152 156 175 176 275 B. ovatus,152 156 176 275 B. thetaiotaomicron,152 156 175 176 275 B. vulgatus,152 156 175 176 275 B. ureolyticus,275 277 Fusobacterium,148 152 156 164 174 176 177 Prevotella bivia,174 275 277 278 279 P. buccae,494 P. disiens,175 278 P. intermedia,177 275 P. melaninogenica,164 175 275 277 278 279 P. oralis,175 275 277 279 Porphyromonas,177 275 494 and Veillonella.175 176 177

-

Active against Helicobacter pylori,164 Entamoeba histolytica, Trichomonas vaginalis, Giardia lamblia, and Balantidium coli.g Acts principally against the trophozoite forms of E. histolytica and has limited activity against the encysted form.g

-

Resistance has been reported in some Bacteroides and T. vaginalis.g

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including metronidazole) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).152 197 430

-

Importance of completing full course of therapy, even if feeling better after a few days.152 197 430

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with metronidazole or other antibacterials in the future.152 197 430

-

Metronidazole extended-release tablets should be taken at least 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals; optimum absorption occurs under fasting conditions.430

-

Advise patients to avoid alcohol during and for at least 1 day after conventional tablets152 or at least 3 days after receiving metronidazole capsules or extended-release tablets.197 430

-

Advise patients to promptly discontinue metronidazole and contact clinician if abnormal neurologic signs occur.152 197 430

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.152 197 430

-

Importance of women informing clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.152 197 430

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.152 197 430 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

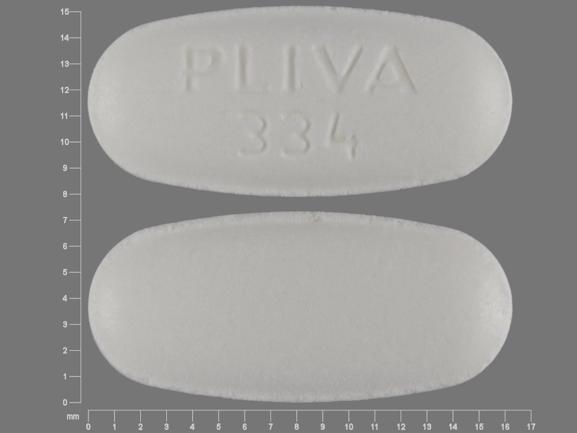

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Capsules |

375 mg |

Flagyl 375 |

Pfizer |

|

Tablets |

250 mg* |

metroNIDAZOLE Tablets |

Mutual |

|

|

500 mg* |

metroNIDAZOLE Tablets |

Mutual |

||

|

Tablets, extended-release, film-coated |

750 mg |

Flagyl ER |

Pfizer |

|

|

Tablets, film-coated |

250 mg* |

Flagyl |

Pfizer |

|

|

500 mg* |

Flagyl |

Pfizer |

||

|

Parenteral |

Injection, for IV infusion only |

5 mg/mL* |

Flagyl I.V. RTU (Viaflex [Baxter]) |

SCS Pharmaceuticals |

|

metroNIDAZOLE Injection (PAB [Braun]) |

Various Manufacturers |

|||

|

metroNIDAZOLE Injection (available in LifeCare and glass containers) |

Abbott |

|||

|

metroNIDAZOLE Injection RTU (Viaflex [Baxter]) |

Various Manufacturers |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Kit |

4 Capsules, Tetracycline Hydrochloride 500 mg 4 Tablets, Metronidazole 250 mg (with povidone) 8 Tablets, chewable, Bismuth Subsalicylate 262.4 mg (with povidone) |

Helidac Therapy (available as 14 blister cards) |

Prometheus |

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

For injection, for IV infusion only |

500 mg (of metronidazole) |

Flagyl I.V. (with mannitol 415 mg) |

SCS Pharmaceuticals |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

Only references cited for selected revisions after 1984 are available electronically.

98. Allen LV Jr, Erickson MA 3rd. Stability of ketoconazole, metolazone, metronidazole, procainamide hydrochloride, and spironolactone in extemporaneously compounded oral liquids. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1996 Sep 1;53(17):2073-8. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/53.17.2073. PMID: 8870895.

99. ASHP. Standardize 4 Safety: compounded oral liquid standards. Updated 2024 Mar. From ASHP website. Updates may be available at ASHP website. https://www.ashp.org/standardize4safety

100. American Academy of Pediatrics. 2006 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 27th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2006.

101. Ursing B, Alm T, Barany F et al. A comparative study of metronidazole and sulfasalazine for active Crohn’s disease: The Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study in Sweden. Gastroenterology. 1982; 83:550-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6124474

102. Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ et al. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn’s disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982; 83:383-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7084615

103. Gilat T. Metronidazole in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1982; 83:702-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6124478

104. Bernstein LH, Frank MS, Brandt LJ et al. Healing of perineal Crohn’s disease with metronidazole, Gastroenterology. 1980; 79:357-65. (IDIS 119497)

105. Sack DM, Peppercorn MA. Drug therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3:158-76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6136027

106. Gugler R, Jensen JC. Interaction between cimetidine and metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1983; 309:1518-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6646177

107. Hansten PD. Metronidazole and cimetidine. Drug Interact Newsl. 1984; 4:7.

108. Lawford R, Sorrell TC. Amebic abscess of the spleen complicated by metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity: a case report. Clin Infect Dis. 1994; 19:346-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7986915

109. Guglielmo BJ, Hohn DC, Koo PJ et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in surgical procedures: a critical analysis of the literature. Arch Surg. 1983; 118:943-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6347124

110. Anon. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2004; 2:27-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15529111

111. Burnakis TG. Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis: principles and guidelines. Pharmacotherapy. 1984; 4:248-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6438611

112. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 1999; 56:1839-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10511234

113. McLean A, Somogyi A, Ioannides-Demos L et al. Successful substitution of rectal metronidazole administration for intravenous use. Lancet. 1983; 1:41-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6129377

114. Giamarellou HJ, Daikos GK. Rectal administration of metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1982; 307:121-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7088042

115. Barker EM, Aitchison JM, Cridland JS et al. Rectal administration of metronidazole in severely ill patients. BMJ. 1983; 287:311-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6409287

116. Mead PB, Gibson M, Schentag JJ et al. Possible alteration of metronidazole metabolism by phenobarbital. N Engl J Med. 1982; 306:1490. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7078600

117. Gupte S. Phenobarbital and metabolism of metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1983; 308:529. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6823276

118. Blackwell AL, Phillips I, Fox AR et al. Anaerobic vaginosis (non-specific vaginitis): clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic findings. Lancet. 1983; 2:1379-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6140492

119. Swedberg J, Steiner JF, Deiss F et al. Comparison of single-dose vs one-week course of metronidazole for symptomatic bacterial vaginosis. JAMA. 1985; 254:1046-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3894707

120. Purdon A, Hanna JH, Morse PL et al. An evaluation of single-dose metronidazole treatment for Gardnerella vaginalis vaginitis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 64:271-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6377153

121. Mindowski WL, Baker CJ, Alleyne D et al. Single oral dose metronidazole therapy for Gardnerella vaginalis vaginitis in adolescent females. J Adolesc Health Care. 1983; 4:113-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6345494

122. Alawattegama AB, Jones BM, Kinghorn GR et al. Single dose versus seven day metronidazole in Gardnerella vaginalis associated non-specific vaginitis. Lancet. 1984; 1:1355. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6145055

124. Lossick JG, Müller M, Gorrell TE. In vitro susceptibility and doses of metronidazole required for cure in cases of refractory vaginal trichomoniasis. J Infect Dis. 1986; 153:948-55. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3486237

125. Cherry RD, Portnoy D, Jabbari M et al. Metronidazole: an alternate therapy for antibiotic-associated colitis. Gastroenterology. 1982; 82:849-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7060906

126. Teasley DG, Gerding DN, Olson MM et al. Prospective randomised trial of metronidazole versus vancomycin for Clostridium-difficile-associated diarrhoea and colitis. Lancet. 1983; 2:1043-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6138597

127. Talbot RW, Walker RC, Beart RW Jr. Changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of Clostridium difficile toxin-associated colitis. Br J Surg. 1986; 73:457-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3719271

128. Bartlett JG. Treatment of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Rev Infect Dis. 1984; 6(Suppl 1):S235-41.

129. Fekety R, Silva J, Buggy B et al. Treatment of antibiotic-associated colitis with vancomycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984; 14(Suppl D):97-102. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6520070

131. Alldredge BK, Barriere SL. Medical treatment for antibiotic colitis. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1985; 19:28.

132. Bartlett JG. Treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis. Gastroenterology. 1985; 89:1192-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3899842

133. Burnakis TG. Metronidazole versus vancomycin for antimicrobial-associated pseudomembranous colitis: the question of cost-effectiveness. Hosp Pharm. 1985; 20:742-4,747.

134. Gross MH. Management of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Clin Pharm. 1985; 4:304-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3891202

135. Travenol Laboratories, Inc. Descriptive information on premixed Mini-Bag container frozen products. Travenol Laboratories, Inc: Deerfield, IL; 1987 Jun.

136. Turner P, Edwards R, Weston V et al. Simultaneous resistance to metronidazole, co-amoxiclav, and imipenem in clinical isolate of Bacteroides fragilis . Lancet. 1995; 345:1275-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7746059

137. Bleicher PA, Charles JH, Sober AJ. Topical metronidazole therapy for rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1987; 123:609-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2953312

138. Eriksson G, Nord CE. Impact of topical metronidazole on the skin and colon microflora in patients with rosacea. Infection. 1987; 15:8-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952597

139. Aronson IK, Rumsfield JA, West DP et al. Evaluation of topical metronidazole gel in acne rosacea. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1987; 21:346-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2952478

140. Veien NK, Christiansen JV, Hjorth N et al. Topical metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis. 1986; 38:209-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2945705

141. Nielsen PG. A double-blind study of I% metronidazole cream versus systemic oxytetracycline therapy for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1983; 109:63-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6222756

142. Dupont C. Metronidazole suspension applied topically for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1984; 111:499. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6237665

143. Nielsen PG. The relapse rate for rosacea after treatment with either oral tetracycline or metronidazole cream. Br J Dermatol. 1983; 109:122. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6222753

144. Nielsen PG. Treatment of rosacea with I% metronidazole cream: a double-blind study. Br J Dermatol. 1983; 108:327-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6219689

145. Saihan EM, Burton JL. A double-blind trial of metronidazole versus oxytetracycline therapy for rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1980; 102:443-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6446314

146. Pye RJ, Burton JL. Treatment of rosacea by metronidazole. Lancet. 1976; 1:1211-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/58258

147. Galderma Laboratories. Metrogel (metronidazole) 0.75% topical gel for topical use only (not for ophthalmic use) prescribing information. In: Physician’s desk reference. 49th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1995:1055.

148. Curatek Pharmaceuticals. MetroGel (metronidazole) 0.75% topical gel product monograph. Elk Grove Village, IL; 1988 Nov.

149. Plotnick BH, Cohen I, Tsang T et al. Metronidazole-induced pancreatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1985; 103:891-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2415031

150. Sanford KA, Mayle JE, Dean HA et al. Metronidazole-associated pancreatitis. Ann Intern Med. 1988; 109:756-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3263823

151. Teicher MH, Altesman RI, Cole JO et al. Possible nephrotoxic interaction of lithium and metronidazole. JAMA. 1987; 257:3365-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3586264

152. Pharmacia. Flagyl (metronidazole tablets) prescribing information. Chicago, IL; 2004 Jan.

153. Anon. Drugs for parasitic infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. Aug 2004. From the Medical Letter web site. http://www.medletter.com

154. Ludwig E, Csiba A, Magyar T et al. Age-associated pharmacokinetic changes of metronidazole. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1983; 21:87-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6840930

155. Ayd FA Jr. Metronidazole-induced lithium intoxication. Int Drug Ther Newsl. 1982; 17:15-6.

156. SCS Pharmaceuticals. Flagyl IV and Flagyl I.V. RTU (metronidazole hydrochloride) prescribing information (dated 1997 Apr 16). In: Physicians’ desk reference. 48th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1998:2563-5.

157. Plosker GL. Possible interaction between ethanol and vaginally administered metronidazole. Clin Pharm. 1987; 6:189-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3665375

158. Almodovar ER. Local application of metronidazole in vaginal ovules for treatment of trichomoniasis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 149:807.

159. de Dios Garcia Diaz J, Moreno Sanchez D, Campos Canter R et al. Metronidazole: pseudomembranous colitis following intravaginal administration. J Medicina Clinica. 1987; 88:652.

160. Lau AH, Evans R, Chang CW et al. Pharmacokinetics of metronidazole in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:1662-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3435113

161. Kleinfeld DI, Sharpe RJ, Donta ST. Parenteral therapy for antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Infect Dis. 1988; 157:389. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3335816

162. Price EH, Wright VM, Walker-Smith JA et al. Clostridium difficile and acute enterocolitis. Arch Dis Child. 1988; 63:543-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3389873

163. Carver PL, Colburn P. Treatment of metronidazole-resistant cases of vaginal trichomoniasis. Clin Pharm. 1988; 7:718-9.

164. Lorian V, ed. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1986:285-93,1016-33,1094.

165. Herman J. Metronidazole for a malodorous pressure sore. Practitioner. 1983; 227:1595-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6634628

166. Tanga MR, Antani JA, Kabade SS. Clinical evaluation of metronidazole as an anti-inflammatory agent. Int Surg. 1975; 60:75-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1090554

167. Miyachi Y, Imamura S, Niwa Y. Anti-oxidant action of metronidazole: a possible mechanism of action in rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 1986; 114:231-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2936372

168. Gamborg Nielsen P. Metronidazole treatment of rosacea. Int J Dermatol. 1988; 27:1-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2964423

169. Bahr V, Ullmann U. The influence of metronidazole and its two main metabolites on murine in vitro lymphocyte transformation. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1983; 2:568-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6667682

170. Gnarpe H, Persson S, Belsheim J. Influence of metronidazole and tinidazole on leukocyte chemotaxis in Crohn’s disease. Infection. 1978; 6(Suppl 1):S107-9.

171. Gnarpe H, Belsheim J, Persson S. Influence of nitroimidazole derivatives on leukocyte migration. Scand J Infect Dis. 1981; 26:68-71.

172. Grove DI, Mahmoud AA, Warren KS. Suppression of cell-mediated immunity by metronidazole. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1977; 54:422-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/328408

173. Gamborg Nielsen P. In vitro antifungal effect of metronidazole on Pityrosporum ovale . Mykosen. 1984; 27:475-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6504071

174. Heard ML, Bawdon RE, Hemsell DL et al. Susceptibility profiles of potential aerobic and anaerobic pathogens isolated from hysterectomy patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1984; 149:133-43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6562855

175. Rolfe RD, Finegold SM. Comparative in vitro activity of new beta-lactam antibiotics against anaerobic bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981; 20:600-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7325628

176. Kesado T, Watanabe K, Asahi Y et al. Susceptibilities of anaerobic bacteria to N-formimidoyl thienamycin (MK0787) and to other antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982; 21:1016-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6956247

177. Wade WG, Addy M. Comparison of in vitro activity of niridazole, metronidazole and tetracycline against subgingival bacteria in chronic periodontitis. J Appl Bacteriol. 1987; 63:455-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3440767

178. Denys GA, Jerris RC, Swenson JM et al. Susceptibility of Propionibacterium acnes clinical isolates to 22 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983; 23:335-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6838191

179. Hoffler U, Niederau W, Pulverer G. Susceptibility of cutaneous Propionibacteria to newer antibiotics. Chemotherapy. 1980; 26:7-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7353441

180. Kurkcuoglu N, Atakan N. Metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1984; 120:837. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6233939

181. Anon. Topical metronidazole for rosacea. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1989; 31:75-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2526918

182. Baker PG, Haig G. Metronidazole in the treatment of chronic pressure sores and ulcers: a comparison with standard treatments in general practice. Practitioner. 1981; 225:569-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7024971

183. Ashford RFU, Plant GT, Maher J et al. Metronidazole in smelly tumours. Lancet. 1980; 1:874-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6103225

184. Doll DC, Doll KJ. Malodorous tumors and metronidazole. Ann Intern Med. 1981; 94:139-40.

185. Sparrow G, Monton M, Rubens RD et al. Metronidazole in smelly tumours. Lancet. 1980; 1:1185. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6103999

186. Koch RL, Beaulieu BB, Chrystal EJT et al. A metronidazole metabolite in human urine and its risk. Science. 1981; 211:398-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7221546

187. Ethanol/metronidazole. In: Tatro DS, Olin BR, eds. Drug interaction facts. St. Louis: JB Lippincott Co; 1988:335.

188. Shank WA Jr, Amerson AB. Metronidazole: an update of its expanding role in clinical medicine. Hosp Formul. 1981; 16:283-97.

189. Beard CM, Kenneth MP, Noller L et al. Lack of evidence for cancer due to use of metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1979; 301:519-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/460304

190. Friedman GD. Cancer after metronidazole. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:519-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7351980

191. Hansten PD. Drug interactions. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1985:96.

192. Anticoagulants, oral/metronidazole. In: Tatro DS, Olin BR, eds. Drug interaction facts. St. Louis: JB Lippincott Co; 1988:82.

193. O’Reilly RA. The stereoselective interaction of warfarin and metronidazole in man. N Engl J Med. 1976; 295:354. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/934223

194. Kazmier FJ. A significant interaction between metronidazole and warfarin. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976; 51:782. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/994556

195. Dean RP, Talbert RL. Bleeding associated with concurrent warfarin and metronidazole therapy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1980; 14:864-6.

196. Hansten PD. Drug interactions. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1985:234.

197. Pharmacia. Flagyl 375 (metronidazole capsules) prescribing information. Chicago, IL; 2005 Apr.

198. Alper MM, Barwin BN, McLean WM et al. Systemic absorption of metronidazole by the vaginal route. Obstet Gynecol. 1985; 65:781-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4000568

199. Anon. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. Med Lett Treat Guid. 2004; 2:67-74.

200. The United States Pharmacopeia, 22nd rev, and The national formulary, 17th ed. Rockville, MD; The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 1990:890-2.

201. Baxter Healthcare Corporation. Descriptive information on premixed liquid products. Baxter Healthcare Corporation; Deerfield, IL: 1994 Feb.

202. Abbott Laboratories. Metronidazole injection, USP (single-dose, flexible container) prescribing information. North Chicago, IL; 1990 Feb.

203. McGaw. Metro IV (sterile metronidazole injection USP). Irvine, CA; 1993 Jan.

204. 3M Pharmaceuticals. MetroGel-Vaginal (metronidazole 0.75% vaginal gel) prescribing information. Northridge, CA; 1997 May.

205. Loo VG, Sherman P, Matlow AG. Helicobacter pylori infection in a pediatric population: in vitro susceptibilities to omeprazole and eight antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:1133-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1510406

206. Knapp CC, Ludwig MD, Washington JA. In vitro activity of metronidazole against Helicobacter pylori as determined by agar dilution and agar diffusion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991; 35:1230-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1929268

207. Ateshkadi A, Lam NP, Johnson CA. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Pharm. 1993; 12:34-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8428432

208. Marshall BJ. Treatment strategies for Helicobacter pylori infection. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:183-98. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449566

209. Murray DM, DuPont HL, Cooperstock M et al. Evaluation of new anti-infective drugs for the treatment of gastritis and peptic ulcer disease associated with infection by Helicobacter pylori . Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15(Suppl 1):S268-73.

210. Becx MCJM, Janssen AJHM, Clasener HAL et al. Metronidazole-resistant Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1990; 335:539-40.

211. Pavicic MJ, Namavar F, Verboom T et al. In vitro susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to several antimicrobial combinations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993; 37:1184-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8517712

212. Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori: its role in disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1992; 15:386-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1520782

213. Israel DM, Hassall E. Treatment and long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori-associated duodenal ulcer disease in children. J Pediatr. 1993; 123:53-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8320625

214. Chiba N, Rao BV, Rademaker JW et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of antibiotic therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori . Am J Gastroenterol. 1992; 87:1716-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1449132

215. Glassman MS. Helicobacter pylori infection in children. A clinical overview. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1992; 31:481-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1643767

216. Peterson WL. Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1991; 324:1043-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2005942

217. Logan RP, Gummett PA, Misiewicz JJ et al. One week eradication regimen for Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1991; 338:1249-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1682653

218. Burette A, Glupczynski Y. On: The who’s and when’s of therapy for Helicobacter pylori . Am J Gastroenterol. 1991; 86:924-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2058644

219. Malfertheiner P. Compliance, adverse events and antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori treatment. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:34-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341989

220. Bell GD, Powell U. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori and its effect in peptic ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:7-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341990

221. Graham DY, Go MF. Evaluation of new antiinfective drugs for Helicobacter pylori infection: revisited and updated. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:293-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8399892

222. Murray DM, DuPont HL. Reply. (Evaluation of new antiinfective drugs for Helicobacter pylori infection: revisited and updated.) Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 17:294- 5.

223. George LL, Borody TJ, Andrews P et al. Cure of duodenal ulcer after eradication of H. pylori . Med J Aust. 1990; 153:145-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1974027

224. Farrell MK. Dr. Apley meets Helicobacter pylori . J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993; 16:118-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8450375

225. Fiocca R, Solcia E, Santoro B. Duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1991; 337:1614. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1675746

226. Marshall BJ. Campylobacter pylori: Its link to gastritis and peptic ulcer disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 1):S87-93.

227. Nomura A, Stemmermann GN, Chyou PH et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma among Japanese Americans in Hawaii. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1132-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1891021

228. Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1127-31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1891020

229. The EUROGAST Study Group.. An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Lancet. 1993; 341:1359-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8098787

230. Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Weaver A et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and Helicobacter pylori infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991; 83:1734-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1770552

231. Forman D, Newell DG, Fullerton F et al. Association between infection with Helicobacter pylori and risk of gastric cancer: evidence from a prospective investigation. BMJ. 1991; 302:1302-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2059685

232. Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection: a novel risk factor in the etiology of gastric cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991; 83:1702-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1770545

233. Parsonnet J. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:89-104. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449573

234. Correa P. Is gastric carcinoma an infectious disease? N Engl J Med. 1991; 325:1170-1.

235. Isaacson PG, Spencer J. Is gastric lymphoma an infectious disease? Hum Pathol. 1993; 24:569-70.

236. Oderda G, Forni M, Dell’Olio D et al. Cure of peptic ulcer associated with eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1990; 335:1599.

237. Bianchi Porro G, Parente F, Lazzaroni M. Short and long term outcome of Helicobacter pylori positive resistant duodenal ulcers treated with colloidal bismuth subcitrate plus antibiotics or sucralfate alone. Gut. 1993; 34:466-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8491391

238. Borody T, Andrews P, Mancuso N et al. Helicobacter pylori reinfection 4 years post-eradication. Lancet. 1992;339:1295. Letter.

239. Hixson LJ, Kelley CL, Jones WN et al. Current trends in the pharmacotherapy for peptic ulcer disease. Arch Intern Med. 1992; 152:726-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1558429

240. Rauws EAJ, Tytgat GNJ. Cure of duodenal ulcer with eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1990; 335:1233-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1971318

241. Hentschel E, Brandst:atter G, Dragosics B et al. Effect of ranitidine and amoxicillin plus metronidazole on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence of duodenal ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:308-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8419816

242. Bayerdorffer E, Mannes GA, Sommer A et al. Long-term follow-up after eradication of Helicobacter pylori with a combination of omeprazole and amoxycillin. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:19-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341987

243. Unge P, Ekstrom P. Effects of combination therapy with omeprazole and an antibiotic on H. pylori and duodenal ulcer disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:17-8.

244. Hunt RH. Hp and pH: implications for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori . Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:12-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8341986

245. Hunt RH. pH and Hp—gastric acid secretion and Helicobacter pylori: implications for ulcer healing and eradication of the organism. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:481-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8470623

246. Goodwin CS. Duodenal ulcer, Campylobacter pylori, and the “leaking roof” concept. Lancet. 1988; 2:1467-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2904580

247. Blaser MJ. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Campylobacter pylori infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 1):S99-106.

248. Barthel JS, Everett ED. Diagnosis of Campylobacter pylori infections: The “gold standard” and the alternatives. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 1):S107-4.

249. Plebani M, Di Mario F, Stanghellini V et al. Serological tests to monitor treatment of Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1992; 340:51-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1351624

250. Bell GD. Anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: clearance, elimination, or eradication? Lancet. 1991; 337:310-1. Letter.

251. Logan RP, Polson RJ, Baron JH et al. Follow-up after anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment. Lancet. 1991; 337:562-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1671932

252. Graham DY, Borsch GM. The who’s and when’s of therapy for Helicobacter pylori . Am J Gastroenterol. 1990; 85:1552-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2252013

253. Yeung CK, Fu KH, Yuen KY et al. Helicobacter pylori and associated duodenal ulcer. Arch Dis Child. 1990; 65:1212-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2248531

254. Oderda G, Dell’Olio D, Morra I et al. Campylobacter pylori gastritis: long term results of treatment with amoxycillin. Arch Dis Child. 1989; 64:326-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2495776

255. Graham DY, Lew GM, Klein PD et al. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on the long-term recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcer. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1992; 116:705-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1558340

256. Axon AT. Helicobacter pylori therapy: effect on peptic ulcer disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991; 6:131-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1912418

257. Cutler AF, Schubert TT. Patient factors affecting Helicobacter pylori eradication with triple therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:505-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8470629

258. Rautelin H, Sepp:al:a K, Renkonen OV et al. Role of metronidazole resistance in therapy of Helicobacter pylori infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992; 36:163-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1590683

259. Weil J, Bell GD, Powell K et al. Helicobacter pylori and metronidazole resistance. Lancet. 1990; 336:1445. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1978897

260. Logan RP, Gummett PA, Hegarty BT et al. Clarithromycin and omeprazole for Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1992; 25:340:239.

261. Graham DY. Treatment of peptic ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori . N Engl J Med. 1993; 328:349-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8419823

262. Hosking SW, Ling TK, Yung MY et al. Randomised controlled trial of short term treatment to eradicate Helicobacter pylori in patients with duodenal ulcer. BMJ. 1992; 305:502-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1392995

263. Bell GD, Powell K, Burridge SM et al. Experience with ”triple’ anti-Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: side effects and the importance of testing the pre-treatment bacterial isolate for metronidazole resistance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1992; 6:427-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1420735

264. Sloane R, Cohen H. Common-sense management of Helicobacter pylori-associated gastroduodenal disease. Personal views. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22:199-206. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449567

265. Katelaris P. Eradicating Helicobacter pylori . Lancet. 1992; 339:54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1345965

266. O’Morain C, Gilvarry J. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1993; 196:30- 3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8102009

267. Patchett S, Beattie S, Leen E et al. Eradicating Helicobacter pylori and symptoms of non-ulcer dyspepsia. BMJ. 1991; 303:1238-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1747644

268. Talley NJ. The role of Helicobacter pylori in nonulcer dyspepsia. A debate—against. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1993; 22(1):153-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8449564

269. Eberhardt R, Kasper G. Effect of oral bismuth subsalicylate on Campylobacter pylori and on healing and relapse rate of peptic ulcer. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 1):S115-9.

270. Adamek RJ, Wegener M, Opferkuch W et al. Successful Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systemic effect of antibiotics? Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:792-3. Letter.

271. Drumm B. Helicobacter pylori. Arch Dis Child. 1990; 65:1278-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2248546

272. Rosioru C, Glassman MS, Halata MS et al. Esophagitis and Helicobacter pylori in children: incidence and therapeutic implications. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993; 88:510-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8470630

273. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations).

274. Graham DY, Lew GM, Evans DG et al. Effect of triple therapy (antibiotics plus bismuth) on duodenal ulcer healing. A randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 115:266-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1854110

275. Goldstein EJC, Citron DM, Cherubin CE et al. Comparative susceptibility of the Bacteroides fragilis group species and other anaerobic bacteria to meropenem, imipenem, piperacillin, cefoxitin, ampicillin/sulbactam, clindamycin, and metronidazole. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993; 31:363-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8486570

276. Spiegel CA. Susceptibility of Mobiluncus species to 23 antimicrobial agents and 15 other compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:249-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3566250

277. Jones BM, Geary I, Lee ME et al. Comparison of the in vitro activities of fenticonazole, other imidazoles, metronidazole, and tetracycline against organisms associated with bacterial vaginosis and skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989; 33:970-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2764547

278. Ohm-Smith MJ, Sweet RL, Hadley WK. In vitro activity of cefbuperazone and other antimicrobial agents against isolates from the female genital tract. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985; 27:958-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4026268

279. Jones BM, Geary I, Alawattegama AB et al. In-vitro and in-vivo activity of metronidazole against Gardnerella vaginalis, Bacteroides spp. and Mobiluncus spp. in bacterial vaginosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985; 16:189-97. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3905748

280. Ralph ED, Amatnieks YE. Relative susceptibilities of Gardnerella vaginalis (Haemophilus vaginalis), Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Bacteroides fragilis to metronidazole and its two major metabolites. Sex Transm Dis. 1980; 7:157-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6779387

281. Spiegel CA, Eschenbach DA, Amsel R et al. Curved anaerobic bacteria in bacterial (nonspecific) vaginosis and their response to antimicrobial therapy. J Infect Dis. 1983; 148:817-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6631073

282. Ralph ED, Amatnieks YE. Metronidazole in treatment against Haemophilus vaginalis (Corynebacterium vaginale). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980; 18:101-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6968175

283. Ralph ED, Austin TW, Pattison FL et al. Inhibition of Haemophilus vaginalis (Corynebacterium vaginale) by metronidazole, tetracycline, and ampicillin. Sex Transm Dis. 1979; 6:199-202. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/388682

284. Ralph ED. Comparative antimicrobial activity of metronidazole and the hydroxy metabolite against Gardnerella vaginalis . Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1983; 40:115-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6607518

285. Greaves WL, Chungafung J, Morris B et al. Clindamycin versus metronidazole in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1988; 72:799-802. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3050654

286. Sobel JD. Bacterial vaginosis. Br J Clin Pract Symp Suppl. 1990; 71:65-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2091736

287. Hillier S, Holmes KK. Bacterial vaginosis. In: Holmes KK, Mardh PA, Sparling PF et al, eds. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990:547-59.

288. Hillier SL, Lipinski C, Briselden AM et al. Efficacy of intravaginal 0.75% metronidazole gel for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 81:963-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8497364

289. Livengood CH 3rd, McGregor JA, Soper DE et al. Bacterial vaginosis: efficacy and safety of intravaginal metronidazole treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994; 170:759-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8141197

290. Hillier SL. Diagnostic microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 169:455-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8357044

291. Anon. Topical treatment for bacterial vaginosis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1992 Nov 27; 34:109.

292. Lugo-Miro VI, Green M, Mazur L. Comparison of different metronidazole therapeutic regimens for bacterial vaginosis: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 1992; 268:92-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1535108

293. Mardh PA. The vaginal ecosystem. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 165:1163-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1951571

294. Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Anderson RJ et al. Statistical evaluation of diagnostic criteria for bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990; 162:155-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1689107

295. Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Scaglione NJ. Bacterial vaginosis: current review with indications for asymptomatic therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991; 165:1210-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1951577

296. Larsson PG, Platz-Christensen JJ, Thejls H et al. Incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease after first-trimester legal abortion in women with bacterial vaginosis after treatment with metronidazole: a double-blind, randomized study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992; 166:100-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1733176

297. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA: Personal communication.

298. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Bulletin: Vaginitis. Number 72. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2006 May.

299. Hill GB. The microbiology of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 169:450-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8357043

300. Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Broekhuizen FF. Advances in the understanding of bacterial vaginosis. J Reprod Med. 1989; 34(Suppl):581-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2677362

301. Sweet RL. New approaches for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993; 169:479-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8357050

302. Lossick JG. Treatment of sexually transmitted vaginosis/vaginitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1990; 12(Suppl 6):S665-81.

303. Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA et al. Nonspecific vaginitis. Diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983; 74:14-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6600371