Diflunisal (Monograph)

Drug class: Reversible COX-1/COX-2 Inhibitors

Warning

- Cardiovascular Risk

-

Increased risk of serious (sometimes fatal) cardiovascular thrombotic events (e.g., MI, stroke).1 500 502 508 Risk may occur early in treatment and may increase with duration of use.500 502 505 506 508 (See Cardiovascular Thrombotic Effects under Cautions.)

-

Contraindicated in the setting of CABG surgery.508

- GI Risk

-

Increased risk of serious (sometimes fatal) GI events (e.g., bleeding, ulceration, perforation of the stomach or intestine).1 Serious GI events can occur at any time and may not be preceded by warning signs and symptoms.1 Geriatric individuals are at greater risk for serious GI events.1 (See GI Effects under Cautions.)

Introduction

Prototypical NSAIA; a difluorophenyl derivative of salicylic acid.1 2 3

Uses for Diflunisal

Consider potential benefits and risks of diflunisal therapy as well as alternative therapies before initiating therapy with the drug.1 Use lowest effective dosage and shortest duration of therapy consistent with the patient’s treatment goals.1

Pain

Relief of mild to moderate pain.1 2

Symptomatic relief of postoperative,2 9 10 postpartum, and orthopedic pain (e.g., musculoskeletal sprains or strains) and visceral pain associated with cancer.2

Inflammatory Disease

Symptomatic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis1 17 18 32 36 and osteoarthritis.1 12

Hereditary Transthyretin-mediated Amyloidosis

Has been used in the treatment of polyneuropathy in patients with hereditary transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis† [off-label].101 102 103 104

Binds to and stabilizes the disease-causing protein (transthyretin), reducing progression of neurologic impairment; however, safety of prolonged use (>2 years) not known.101 102 103 104 105

Diflunisal Dosage and Administration

General

-

Consider potential benefits and risks of diflunisal therapy as well as alternative therapies before initiating therapy with the drug.1

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally.1 75 If GI disturbances occur, administer with meals or milk.1 75

Do not break, crush, or chew diflunisal tablets.1 75 Swallow intact.1 75

Dosage

To minimize the potential risk of adverse cardiovascular and/or GI events, use lowest effective dosage and shortest duration of therapy consistent with the patient’s treatment goals.1 Adjust dosage based on individual requirements and response; attempt to titrate to the lowest effective dosage.1

Exhibits concentration-dependent pharmacokinetics.1 75 Plasma diflunisal concentrations increase more than proportionally with increasing and/or multiple doses; use caution when adjusting doses.1 75

Adults

Pain

Oral

Mild to moderate pain: Initially, 1 g, followed by 500 mg every 12 hours.1 75 Some patients may require 500 mg every 8 hours.1 75

Patients with lower dosage requirements (less severe pain, heightened response, low body weight): Initially, 500 mg, followed by 250 mg every 8–12 hours.1

Inflammatory Diseases

Osteoarthritis or Rheumatoid Arthritis

Oral500 mg–1 g daily in 2 divided doses.1 75

Prescribing Limits

Adults

Oral

Special Populations

Geriatric Patients

Select dosage with caution because of age-related decreases in renal function.1

Initially, 500 mg, followed by 250 mg every 8–12 hours.1

Cautions for Diflunisal

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to diflunisal or any ingredient in the formulation.1

-

History of asthma, urticaria, or other sensitivity reaction precipitated by aspirin or other NSAIAs.1 48 49 50 51 52

-

In the setting of CABG surgery.508

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Cardiovascular Thrombotic Effects

NSAIAs (selective COX-2 inhibitors, prototypical NSAIAs) increase the risk of serious adverse cardiovascular thrombotic events (e.g., MI, stroke) in patients with or without cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease.500 502 508

Findings of FDA review of observational studies, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials, and other published information500 501 502 indicate that NSAIAs may increase the risk of such events by 10–50% or more, depending on the drugs and dosages studied.500

Relative increase in risk appears to be similar in patients with or without known underlying cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease, but the absolute incidence of serious NSAIA-associated cardiovascular thrombotic events is higher in those with cardiovascular disease or risk factors for cardiovascular disease because of their elevated baseline risk.500 502 506 508

Increased risk may occur early (within the first weeks) following initiation of therapy and may increase with higher dosages and longer durations of use.500 502 505 506 508

In controlled studies, increased risk of MI and stroke observed in patients receiving a selective COX-2 inhibitor for analgesia in first 10–14 days following CABG surgery.508

In patients receiving NSAIAs following MI, increased risk of reinfarction and death observed beginning in the first week of treatment.505 508

Increased 1-year mortality rate observed in patients receiving NSAIAs following MI;500 508 511 absolute mortality rate declined somewhat after the first post-MI year, but the increased relative risk of death persisted over at least the next 4 years.508 511

Some systematic reviews of controlled observational studies and meta-analyses of randomized studies suggest naproxen may be associated with lower risk of cardiovascular thrombotic events compared with other NSAIAs.97 98 99 100 500 501 502 503 506 FDA states that limitations of these studies and indirect comparisons preclude definitive conclusions regarding relative risks of NSAIAs.500

Use NSAIAs with caution and careful monitoring (e.g., monitor for development of cardiovascular events throughout therapy, even in those without prior cardiovascular symptoms) and at the lowest effective dosage for the shortest duration necessary.1 500 508

Some clinicians suggest that it may be prudent to avoid NSAIA use, whenever possible, in patients with cardiovascular disease.505 511 512 516 Avoid use in patients with recent MI unless benefits of therapy are expected to outweigh risk of recurrent cardiovascular thrombotic events; if used, monitor for cardiac ischemia.508 Contraindicated in the setting of CABG surgery.508

No consistent evidence that concomitant use of low-dose aspirin mitigates the increased risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with NSAIAs.1 94 502 508 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

GI Effects

Serious GI toxicity (e.g., bleeding, ulceration, perforation) can occur with or without warning symptoms; increased risk in those with a history of GI bleeding or ulceration, geriatric patients, smokers, those with alcohol dependence, and those in poor general health.1 82 84 91

For patients at high risk for complications from NSAIA-induced GI ulceration (e.g., bleeding, perforation), consider concomitant use of misoprostol;29 64 82 83 alternatively, consider concomitant use of a proton-pump inhibitor (e.g., lansoprazole, omeprazole) or use of an NSAIA that is a selective inhibitor of COX-2 (e.g., celecoxib).29 64 82

Hypertension

Hypertension and worsening of preexisting hypertension reported; either event may contribute to the increased incidence of cardiovascular events.1 Use with caution in patients with hypertension; monitor BP.1

Impaired response to ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, β-blockers, and certain diuretics may occur.1 508 509 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Heart Failure and Edema

Fluid retention and edema reported.1 508

NSAIAs (selective COX-2 inhibitors, prototypical NSAIAs) may increase morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure.500 501 504 507 508

NSAIAs may diminish cardiovascular effects of diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or angiotensin II receptor antagonists used to treat heart failure or edema.508 (See Specific Drugs under Interactions.)

Manufacturer recommends avoiding use in patients with severe heart failure unless benefits of therapy are expected to outweigh risk of worsening heart failure; if used, monitor for worsening heart failure.508

Some experts recommend avoiding use, whenever possible, in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction and current or prior symptoms of heart failure.507

Renal Effects

Direct renal injury, including renal papillary necrosis, reported in patients receiving long-term NSAIA therapy.1

Potential for overt renal decompensation.1 38 40 41 42 43 44 45 Increased risk of renal toxicity in patients with renal or hepatic impairment or heart failure, in patients with volume depletion, in geriatric patients, and in those receiving a diuretic, ACE inhibitor, or angiotensin II receptor antagonist.1 39 41 (See Renal Impairment under Cautions.)

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Anaphylactoid reactions reported.1 Immediate medical intervention and discontinuance for anaphylaxis.1

Avoid in patients with aspirin triad (aspirin sensitivity, asthma, nasal polyps); caution in patients with asthma.1

Potentially fatal or life-threatening syndrome of multi-organ hypersensitivity (i.e., drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS]) reported in patients receiving NSAIAs.1201 Clinical presentation is variable, but typically includes eosinophilia, fever, rash, lymphadenopathy, and/or facial swelling, possibly associated with other organ system involvement (e.g., hepatitis, nephritis, hematologic abnormalities, myocarditis, myositis).1201 Symptoms may resemble those of acute viral infection.1201 Early manifestations of hypersensitivity (e.g., fever, lymphadenopathy) may be present in the absence of rash.1201 If signs or symptoms of DRESS develop, discontinue diflunisal and immediately evaluate the patient.1201

Dermatologic Reactions

Serious skin reactions (e.g., exfoliative dermatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis) can occur without warning.1 Discontinue at first appearance of rash or any other sign of hypersensitivity (e.g., blisters, fever, pruritus).1

General Precautions

Hepatic Effects

Severe reactions including jaundice, fatal fulminant hepatitis, liver necrosis, and hepatic failure (sometimes fatal) reported rarely with NSAIAs.1

Elevations of serum ALT or AST reported.1

Monitor for symptoms and/or signs suggesting liver dysfunction; monitor abnormal liver function test results.1 Discontinue if signs or symptoms of liver disease or systemic manifestations (e.g., eosinophilia, rash) occur or if liver function test abnormalities persist or worsen.1

Hematologic Effects

Anemia reported rarely.1 Determine hemoglobin concentration or hematocrit in patients receiving long-term therapy if signs or symptoms of anemia occur.1

May inhibit platelet aggregation and prolong bleeding time.1

Ocular Effects

Visual disturbances reported; ophthalmic evaluation recommended if visual changes occur.1

Other Precautions

Not a substitute for corticosteroid therapy; not effective in the management of adrenal insufficiency.1

May mask certain signs of infection.1

Obtain CBC and chemistry profile periodically during long-term use.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Use of NSAIAs during pregnancy at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation can cause premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; use at about ≥20 weeks’ gestation associated with fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment.1200 1201

Effects of NSAIAs on the human fetus during third trimester of pregnancy include prenatal constriction of the ductus arteriosus, tricuspid incompetence, and pulmonary hypertension; nonclosure of the ductus arteriosus during the postnatal period (which may be resistant to medical management); and myocardial degenerative changes, platelet dysfunction with resultant bleeding, intracranial bleeding, renal dysfunction or renal failure, renal injury or dysgenesis potentially resulting in prolonged or permanent renal failure, oligohydramnios, GI bleeding or perforation, and increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis.1202

Avoid use of NSAIAs in pregnant women at about ≥30 weeks’ gestation; if use required between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation, use lowest effective dosage and shortest possible duration of treatment, and consider monitoring amniotic fluid volume via ultrasound examination if treatment duration >48 hours; if oligohydramnios occurs, discontinue drug and follow up according to clinical practice.1200 1201 (See Advice to Patients.)

Fetal renal dysfunction resulting in oligohydramnios and, in some cases, neonatal renal impairment observed, on average, following days to weeks of maternal NSAIA use; infrequently, oligohydramnios observed as early as 48 hours after initiation of NSAIAs.1200 1201 Oligohydramnios is often, but not always, reversible (generally within 3–6 days) following NSAIA discontinuance.1200 1201 Complications of prolonged oligohydramnios may include limb contracture and delayed lung maturation.1200 1201 In limited number of cases, neonatal renal dysfunction (sometimes irreversible) occurred without oligohydramnios.1200 1201 Some neonates have required invasive procedures (e.g., exchange transfusion, dialysis).1200 1201 Deaths associated with neonatal renal failure also reported.1200 Limitations of available data (lack of control group; limited information regarding dosage, duration, and timing of drug exposure; concomitant use of other drugs) preclude a reliable estimate of the risk of adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes with maternal NSAIA use.1201 Available data on neonatal outcomes generally involved preterm infants; extent to which risks can be generalized to full-term infants is uncertain.1201

Animal data indicate important roles for prostaglandins in kidney development and endometrial vascular permeability, blastocyst implantation, and decidualization.1201 In animal studies, inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis increased pre- and post-implantation losses; also impaired kidney development at clinically relevant doses.1201

Diflunisal was maternotoxic, embryotoxic, and teratogenic in animal studies.1201

Effects of diflunisal on labor and delivery not known.1201 In animal studies, NSAIAs increased incidence of dystocia, delayed parturition, and decreased pup survival.1201

Lactation

Distributed into milk; discontinue nursing or the drug.1

Fertility

NSAIAs may be associated with reversible infertility in some women.1203 Reversible delays in ovulation observed in limited studies in women receiving NSAIAs; animal studies indicate that inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis can disrupt prostaglandin-mediated follicular rupture required for ovulation.1203

Consider withdrawal of NSAIAs in women experiencing difficulty conceiving or undergoing evaluation of infertility.1203

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <12 years of age.1

Use in children with varicella infections or influenza-type illnesses may be associated with an increased risk of developing Reye’s syndrome.1

Geriatric Use

Geriatric patients appear to tolerate GI ulceration and bleeding less well than other individuals.1 Fatal adverse GI effects reported more frequently in geriatric patients than younger adults.1

Select dosage with caution because of age-related decreases in renal function.1 May be useful to monitor renal function.1

Renal Impairment

Use with caution in patients with renal impairment.1 Use not recommended in patients with severe renal impairment; close monitoring of renal function if used.1

Drug and its metabolites eliminated principally via the kidney.1

Common Adverse Effects

Nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, GI pain, diarrhea, constipation, flatulence, somnolence, insomnia, dizziness, tinnitus, rash, headache, fatigue/tiredness.1

Drug Interactions

Protein-bound Drugs

Potential for diflunisal to be displaced from binding sites by, or to displace from binding sites, other protein-bound drugs.1 2 5 Observe for adverse effects if used with other protein-bound drugs.b

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

ACE inhibitors |

Reduced BP response to ACE inhibitor1 Possible deterioration of renal function in individuals with renal impairment1 |

Monitor BP1 |

|

Acetaminophen |

Increased plasma acetaminophen concentrations1 Possible increased GI toxicity1 |

Use concomitantly with caution; closely monitor hepatic function1 |

|

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists |

Reduced BP response to angiotensin II receptor antagonist1 Possible deterioration of renal function in individuals with renal impairment1 |

Monitor BP1 |

|

Antacids |

Possible decreased plasma diflunisal concentrations1 |

|

|

Anticoagulants (warfarin) |

Possible bleeding complications and increases in PT1 |

Monitor PT during and for several days following concomitant therapy1 Adjust anticoagulant dosage as needed1 |

|

Aspirin |

Possible decreased plasma diflunisal concentrations1 5 Increased risk of GI ulceration and other complications1 No consistent evidence that low-dose aspirin mitigates the increased risk of serious cardiovascular events associated with NSAIAs94 502 508 |

Manufacturers state that concomitant use not recommended1 |

|

Corticosteroids |

||

|

Cyclosporine |

Increased nephrotoxic effects of cyclosporine1 |

Caution advised; closely monitor renal function1 |

|

Diuretics (furosemide, thiazides) |

Increased risk of developing renal failure1 Possible reduced natriuretic effects1 Increased plasma hydrochlorothiazide concentrations 1 Potential for decreased hyperuricemic effects of hydrochlorothiazide1 |

Monitor for diuretic efficacy and renal failure1 |

|

Lithium |

Increased plasma lithium concentrations1 |

Monitor for lithium toxicity1 |

|

Methotrexate |

Possible toxicity associated with increased plasma methotrexate concentrations56 57 58 59 60 61 62 |

Use concomitantly with caution1 |

|

NSAIAs |

Possible additive adverse GI effects1 |

|

|

Pemetrexed |

Possible increased risk of pemetrexed-associated myelosuppression, renal toxicity, and GI toxicity1203 |

Short half-life NSAIAs (e. g., diclofenac, indomethacin): Avoid administration beginning 2 days before and continuing through 2 days after pemetrexed administration1203 Longer half-life NSAIAs (e.g., meloxicam, nabumetone): In the absence of data, avoid administration beginning at least 5 days before and continuing through 2 days after pemetrexed administration1203 Patients with Clcr 45–79 mL/minute: Monitor for myelosuppression, renal toxicity, and GI toxicity1203 |

|

Thrombolytic agents (streptokinase) |

Possible increased risk of bleeding complications28 |

Use concomitantly with caution 28 |

|

Tolbutamide |

Concomitant use does not appear to affect the hypoglycemic response or plasma tolbutamide concentrations1 |

Diflunisal Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Well absorbed following oral administration; peak plasma concentrations usually attained within 2–3 hours.1 2 5

Onset

Analgesic effect occurs within 1 hour; maximum analgesic effect occurs within 2–3 hours.1

Food

Food slightly decreases the rate but not the extent of absorption.5

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into CSF and crosses the placenta in small amounts in animals.1 Distributed into human milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized in the liver to glucuronide conjugates.1 2 8

Elimination Route

Excreted in urine (90%) mainly as glucuronide conjugates and in feces (<5%).1 2 5 8

Half-life

Special Populations

In patients with severe renal impairment (i.e., Clcr <2 mL/minute), terminal half-life is approximately 68–138 hours.7

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets, film-coated

<40°C; preferably 15–30°C.34

Actions

-

Inhibits cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) and COX-2.76 77 78 79 80 81

-

Pharmacologic actions similar to those of other prototypical NSAIAs;2 5 exhibits anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic activity.1 2

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of reading the medication guide for NSAIAs that is provided each time the drug is dispensed.1

-

Risk of serious cardiovascular events (e.g., MI, stroke).1 500 508

-

Risk of GI bleeding and ulceration.1

-

Risk of serious skin reactions, DRESS, and anaphylactoid and other sensitivity reactions.1 1201

-

Risk of hepatotoxicity.1

-

Importance of seeking immediate medical attention if signs and symptoms of a cardiovascular event (chest pain, dyspnea, weakness, slurred speech) occur.1 500 508

-

Importance of notifying clinician if signs and symptoms of GI ulceration or bleeding, unexplained weight gain, or edema develops.1

-

Advise patients to stop taking diflunisal immediately if they develop any type of rash or fever and to promptly contact their clinician.1201 Importance of seeking immediate medical attention if an anaphylactic reaction occurs.1

-

Importance of discontinuing therapy and contacting clinician immediately if signs and symptoms of hepatotoxicity (nausea, fatigue, lethargy, pruritus, jaundice, upper right quadrant tenderness, flu-like symptoms) occur.1

-

Risk of heart failure or edema; importance of reporting dyspnea, unexplained weight gain, or edema.508

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of avoiding NSAIA use beginning at 20 weeks’ gestation unless otherwise advised by a clinician; importance of avoiding NSAIAs beginning at 30 weeks’ gestation because of risk of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus; monitoring for oligohydramnios may be necessary if NSAIA therapy required for >48 hours’ duration between about 20 and 30 weeks’ gestation.1200 1201

-

Advise women who are trying to conceive that NSAIAs may be associated with a reversible delay in ovulation.1203

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

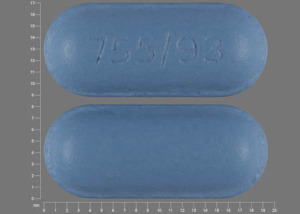

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

500 mg* |

Diflunisal Tablets |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Merck & Co. Dolobid (diflunisal) tablets prescribing information. Whitehouse Station, NJ; 2006 Feb.

2. Brogden RN, Heel RC, Pakes GE et al. Diflunisal: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use in pain and musculoskeletal strains and sprains and pain in osteoarthritis. Drugs. 1980; 19:84-106. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6988202

3. Hannah J, Ruyle WV, Jones H et al. Discovery of diflunisal. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 4(Suppl):7S-13S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/328036 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1428845/

4. Stone CA, Van Arman CG, Lotti VJ et al. Pharmacology and toxicology of diflunisal. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 4(Suppl):19S-29S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/301744 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1428841/

5. Davies RO. Review of the animal and clinical pharmacology of diflunisal. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3(Suppl):9S-22S.

6. Green D, Davies RO, Holmes GI et al. Effects of diflunisal on platelet function and fecal blood loss. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3(Suppl):65S-9S.

7. Verbeeck R, Tjandramaga TB, Mullie A et al. Biotransformation of diflunisal and renal excretion of its glucuronides in renal insufficiency. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979; 7:273-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/427004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1429486/

8. Tempero KF, Cirillo VJ, Steelman SL. Diflunisal: a review of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, drug interactions, and special tolerability studies in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 4(Suppl):31S-6S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/328032 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1428837/

9. Forbes JA, Calderazzo JP, Bowser MW et al. A 12-hour evaluation of the analgesic efficacy of diflunisal, aspirin, and placebo in postoperative dental pain. J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 22:89-96. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7068938

10. Van Winzum C, Rodda B. Diflunisal: efficacy in post-operative pain. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1977; 4(Suppl):39S-43S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/328033 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1428846/

11. Forbes JA, Beaver WT, White EH et al. Diflunisal: a new oral analgesic with an unusually long duration of action. JAMA. 1982; 248:2139-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6750171

12. Umbenhauer ER. Diflunisal in the treatment of the pain of osteoarthritis. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3(Suppl):55S-60S.

13. Rider JA. Comparison of fecal blood loss after use of aspirin and diflunisal. Pharmacotherapy. 1983; 3(Suppl):61S-4S.

14. Dieppe PA, Doyle DV, Burry HC. Renal damage during treatment with antirheumatic drugs. Br Med J. 1978; 2:664. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/308826 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1607408/

15. Upadhyay HP, Gupta SK. Diflunisal (Dolobid) overdose. Br Med J. 1978; 2:640. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/698637 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1607479/

16. Flower RJ, Moncada S, Vane JR. Drug therapy of inflammation: analgesic-antipyretics and anti-inflammatory agents; drugs employed in the treatment of gout. In: Gilman AG, Goodman L, Gilman A, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 6th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1980:682-93.

17. DeSilva M, Hazleman BL, Dippy JE. Diflunisal and aspirin: a comparative study in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1980; 19:126-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6996072

18. Palmer DG, Ferry DG, Gibbins BL et al. Ibuprofen and diflunisal in rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind comparative trial. N Z Med J. 1981; 94:45-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7024866

19. The United States pharmacopeia, 25th rev, and The national formulary, 20th ed. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 2002: 567.

20. Simon LS, Mills JA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1980; 302:1179-85. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6988717

21. Ferreira SH, Lorenzetti BB, Correa FMA. Central and peripheral antianalgesic action of aspirin-like drugs. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978; 53:39-48. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/310771

22. Atkinson DC, Collier HOJ. Salicylates: molecular mechanism of therapeutic action. Adv Pharmacol Chemother. 1980; 17:233-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7004141

23. Bernheim HA, Block LH, Atkins E. Fever: pathogenesis, pathophysiology, and purpose. Ann Intern Med. 1979; 91:261-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/223485

24. Dresse A, Fischer P, Gerard MA et al. Uricosuric properties of diflunisal in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1979; 7:267-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/427003 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1429497/

25. Miller TA, Jacobson ED. Gastrointestinal cytoprotection by prostaglandins. Gut. 1979; 20:875-87. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/391656 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1412707/

26. Robert A. Cytoprotection by prostaglandins. Gastroenterology. 1979; 77:761-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38173

27. Willkens RF. The use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. JAMA. 1978; 240:1632-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/691156

28. Hoechst-Roussel. Streptase prescribing information. Somerville, NJ; 1980 Aug.

29. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Rheumatoid Arthritis Guidelines. Guidelines for the management of rheumatoid arthritis: 2002 update. Arthritis Rheum. 2002; 46:328-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11840435

30. Hart FD. Rheumatic disorders. In: Avery GS, ed. Drug treatment: principles and practice of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2nd ed. New York: ADIS Press; 1980:861-2.

31. De Vroey P. A double-blind comparison of diflunisal and aspirin in the treatment of post-operative pain after episiotomy. Curr Med Res Opin. 1978; 5:544-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/359247

32. Merck, Sharp & Dohme. Dolobid (diflunisal)—an anti-inflammatory analgesic. West Point, PA. 1983 Aug.

33. Dal Pino E (Merck, Sharp & Dohme, West Point, PA): Personal communication; 1984 Feb 24.

34. USP DI. Vol. 1: 1984 Drug information for the health care provider. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 2002: 430-1.

35. Gosselin RE, Hodge HC, Smith RP et al. Clinical toxicology of commercial products: acute poisoning. 5th ed. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Co; 1984:I-10.

36. Turner RA, Whipple JP, Shackleford RW. Diflunisal 500–700 mg versus aspirin 2600–3900 mg in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Pharmacotherapy. 1984; 4:151-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6377249

38. Wolf RE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1984; 144:1658-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6235791

39. Robinson DR. Prostaglandins and the mechanism of action of anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1983; 10:26-31.

40. O’Brien WM. Pharmacology of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: practical review for clinicians. Am J Med. 1983; 10:32-9.

41. Clive DM, Stoff JS. Renal syndromes associated with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1984; 310:563-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6363936

42. Adams DH, Michael J, Bacon PA et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and renal failure. Lancet. 1986; 1:57-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2867313

43. Henrich WL. Nephrotoxicity of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983; 2:478-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6823966

44. Kimberly RP, Bowden RE, Keiser HR et al. Reduction of renal function by newer nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Am J Med. 1978; 64:804-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/645744

45. Corwin HL, Bonventre JV. Renal insufficiency associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Am J Kidney Dis. 1984; 4:147-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6475945

46. Settipane GA. Adverse reactions to aspirin and other drugs. Arch Intern Med. 1981; 141:328-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7008734

47. Weinberger M. Analgesic sensitivity in children with asthma. Pediatrics. 1978; 62(Suppl):910-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/103067

48. Settipane GA. Aspirin and allergic diseases: a review. Am J Med. 1983; 74(Suppl):102-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6344621

49. VanArsdel PP Jr. Aspirin idiosyncracy and tolerance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 73:431-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6423718

50. Stevenson DD. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of adverse reactions to aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984; 74(4 Part 2):617-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6436354

51. Stevenson DD, Mathison DA. Aspirin sensitivity in asthmatics: when may this drug be safe? Postgrad Med. 1985; 78:111-3,116-9. (IDIS 205854)

52. Pleskow WW, Stevenson DD, Mathison DA et al. Aspirin desensitization in aspirin-sensitive asthmatic patients: clinical manifestations and characterization of the refractory period. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982; 69(1 Part 1):11-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7054250

53. Cook DJ, Achong MR, Murphy FR. Three cases of diflunisal hypersensitivity. CMAJ. 1988; 138:1029-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2967101 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1267889/

54. Food and Drug Administration. Labeling revisions for NSAIDs. FDA Drug Bull. 1989; 19:3-4.

55. Palmer JF. Letter sent to Berger ET of Merck Sharp & Dohme regarding labeling revisions about gastrointestinal adverse reactions to Dolobid (diflunisal). Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration, Division of Oncology and Radiopharmaceutical Drug Products; 1988 Sep.

56. Thyss A, Milano G, Kubar J et al. Clinical and pharmacokinetic evidence of a life-threatening interaction between methotrexate and ketoprofen. Lancet. 1986; 1:256-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2868265

57. Ellison NM, Servi RJ. Acute renal failure and death following sequential intermediate-dose methotrexate and 5-FU: a possible adverse effect due to concomitant indomethacin administration. Cancer Treat Rep. 1985; 69:342-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3978662

58. Singh RR, Malaviya AN, Pandey JN et al. Fatal interaction between methotrexate and naproxen. Lancet. 1986; 1:1390. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2872507

59. Day RO, Graham GG, Champion GD et al. Anti-rheumatic drug interactions. Clin Rheum Dis. 1984; 10:251-75. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6150784

60. Daly HM, Scott GL, Boyle J et al. Methotrexate toxicity precipitated by azapropazone. Br J Dermatol. 1986; 114:733-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3718865

61. Hansten PD, Horn JR. Methotrexate interactions: ketoprofen (Orudis). Drug Interact Newsl. 1986; 6(Updates):U5-6.

62. Maiche AG. Acute renal failure due to concomitant action of methotrexate and indomethacin. Lancet. 1986; 1:1390. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2872506

63. Searle. Cytotec (misoprostol) prescribing information. Skokie, IL; 1989 Jan.

64. Anon. Drugs for rheumatoid arthritis. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2000; 42:57-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10887424

65. Soll AH, Weinstein WM, Kurata J et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and peptic ulcer disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:307-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1987878

67. Ciba Geigy, Ardsley, NY: Personal communication on diclofenac 28:08.04.

68. Reviewers’ comments (personal observation) on diclofenac 28:08.04.

69. Corticosteroid interactions: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In: Hansten PD, Horn JR. Drug interactions and updates. Vancouver, WA: Applied Therapeutics, Inc; 1993:562.

70. Garcia Rodriguez LA, Jick H. Risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation associated with individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Lancet. 1994; 343:769-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7907735

71. Hollander D. Gastrointestinal complications of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: prophylactic and therapeutic strategies. Am J Med. 1994; 96:274-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8154516

72. Schubert TT, Bologna SD, Yawer N et al. Ulcer risk factors: interaction between Helicobacter pylori infection, nonsteroidal use, and age. Am J Med. 1993; 94:413-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8475935

73. Piper JM, Ray WA, Daugherty JR et al. Corticosteroid use and peptic ulcer disease: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ann Intern Med. 1991; 114:735-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2012355

74. Bateman DN, Kennedy JG. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and elderly patients: the medicine may be worse than the disease. BMJ. 1995; 310:817-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7711609 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2549212/

75. West Point Pharma. Diflunisal tablets, USP, prescribing information. West Point, PA; 1995 Oct.

76. Hawkey CJ. COX-2 inhibitors. Lancet. 1999; 353:307-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9929039

77. Kurumbail RG, Stevens AM, Gierse JK et al. Structural basis for selective inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 by anti-inflammatory agents. Nature. 1996; 384:644-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8967954

78. Riendeau D, Charleson S, Cromlish W et al. Comparison of the cyclooxygenase-1 inhibitory properties of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and selective COX-2 inhibitors, using sensitive microsomal and platelet assays. Can J Phsiol Pharmacol. 1997; 75:1088-95.

79. DeWitt DL, Bhattacharyya D, Lecomte M et al. The differential susceptibility of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthases-1 and -2 to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: aspirin derivatives as selective inhibitors. Med Chem Res. 1995; 5:325-43.

80. Cryer B, Dubois A. The advent of highly selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase— a review. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediators. 1998; 56:341-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9990677

81. Simon LS. Role and regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 during inflammation. Am J Med. 1999; 106(Suppl 5B):37-42S.

82. Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. N Engl J Med. 1999; 340:1888-99. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10369853

83. Lanza FL, and the members of the Ad Hoc Committee on Practice Parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. A guideline for the treatment and prevention of NSAID-induced ulcers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998; 93:2037-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9820370

84. Singh G, Triadafilopoulos G. Epidemiology of NSAID induced gastrointestinal complications. J Rheumatol. 1999; 26(suppl 56):18-24.

85. in’t Veld BA, Ruitenberg A, Hofman A et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1515-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11794217

86. Breitner JCS, Zandi PP. Do nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease? N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1567-8. Editorial.

87. McGeer PL, Schulzer M, McGeer EG. Arthritis and anti-inflammatory agents as possible protective factors for Alzheimer’s disease: a review of 17 epidemiologic studies. Neurology. 1996; 47:425-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8757015

88. Beard CM, Waring SC, O’sBrien PC et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and Alzheimer’s disease : a case-control study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1980 through 1984. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998; 73:951-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9787743

89. in’t Veld BA, Launer LJ, Hoes AW et al. NSAIDs and incident Alzheimer’s disease: the Rotterdam Study. Neurobiol Aging. 1998; 19:607-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10192221

90. Stewart WF, Kawas C, Corrada M et al. Risk of Alzheimer’s disease and duration of NSAID use. Neurology. 1997; 48:626-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9065537

91. Pharmacia. Daypro (oxaprozin) caplets prescribing information. Chicago, IL; 2002 May.

92. Chan FKL, Hung LCT, Suen BY et al. Celecoxib versus diclofenac and omeprazole in reducing the risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding in patients with arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:2104-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12501222

93. Graham DY. NSAIDs, Helicobacter pylori, and Pandora’s box. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347:2162-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12501230

94. Food and Drug Administration. Analysis and recommendations for agency action regarding non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cardiovascular risk. 2005 Apr 6.

95. Cush JJ. The safety of COX-2 inhibitors: deliberations from the February 16-18, 2005, FDA meeting. From the American College of Rheumatology website. Accessed 2005 Oct 12. http://www.rheumatology.org

96. Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Diovan (valsartan) capsules prescribing information (dated 1997 Apr). In: Physicians’ desk reference. 53rd ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1999:2013-5.

97. McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk and inhibition of cyclooxygenase: a systematic review of observational studies of selective and nonselective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase 2. JAMA. 2006; 296: 1633-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16968831

98. Kearney PM, Baigent C, Godwin J et al. Do selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors and traditional non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase the risk of atherothrombosis? Meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2006; 332: 1302-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16740558 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1473048/

99. Graham DJ. COX-2 inhibitors, other NSAIDs, and cardiovascular risk; the seduction of common sense. JAMA. 2006; 296:1653-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16968830

100. Chou R, Helfand M, Peterson K et al. Comparative effectiveness and safety of analgesics for osteoarthritis. Comparative effectiveness review no. 4. (Prepared by the Oregon evidence-based practice center under contract no. 290-02-0024.) . Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2006 Sep. http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/final.cfm

101. Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013; 8:31. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23425518

102. Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013; 310:2658-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24368466

103. Sekijima Y, Tojo K, Morita H et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term diflunisal administration in hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2015; 22:79-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26017328

104. Hawkins PN, Ando Y, Dispenzeri A et al. Evolving landscape in the management of transthyretin amyloidosis. Ann Med. 2015; 47:625-38. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26611723

105. Sekijima Y, Dendle MA, Kelly JW. Orally administered diflunisal stabilizes transthyretin against dissociation required for amyloidogenesis. Amyloid. 2006; 13:236-49. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17107884

500. Food and Drug Administration. Drug safety communication: FDA strengthens warning that non-aspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can cause heart attacks or strokes. Silver Spring, MD; 2015 Jul 9. From the FDA web site. Accessed 2016 Mar 22. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm451800.htm

501. Coxib and traditional NSAID Trialists' (CNT) Collaboration, Bhala N, Emberson J et al. Vascular and upper gastrointestinal effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: meta-analyses of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2013; 382:769-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23726390 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3778977/

502. Food and Drug Administration. FDA briefing document: Joint meeting of the arthritis advisory committee and the drug safety and risk management advisory committee, February 10-11, 2014. From FDA web site http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/ArthritisAdvisoryCommittee/UCM383180.pdf

503. Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S et al. Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011; 342:c7086. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21224324 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3019238/

504. Gislason GH, Rasmussen JN, Abildstrom SZ et al. Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity associated with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169:141-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19171810

505. Schjerning Olsen AM, Fosbøl EL, Lindhardsen J et al. Duration of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and impact on risk of death and recurrent myocardial infarction in patients with prior myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2011; 123:2226-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21555710

506. McGettigan P, Henry D. Cardiovascular risk with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: systematic review of population-based controlled observational studies. PLoS Med. 2011; 8:e1001098. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21980265 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181230/

507. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013; 62:e147-239. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23747642

508. Rising Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Diflunisal tablets prescribing information. Allendale, NJ; 2016 May.

509. Cumberland Pharmaceuticals Inc. Caldolor (ibuprofen) injection prescribing information. Nashville, TN; 2016 Apr.

b. AHFS drug information 2006. McEvoy GK, ed. Diflunisal. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2006:2022-2026.

511. Olsen AM, Fosbøl EL, Lindhardsen J et al. Long-term cardiovascular risk of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use according to time passed after first-time myocardial infarction: a nationwide cohort study. Circulation. 2012; 126:1955-63. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22965337

512. Olsen AM, Fosbøl EL, Lindhardsen J et al. Cause-specific cardiovascular risk associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among myocardial infarction patients--a nationwide study. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e54309.

516. Bavry AA, Khaliq A, Gong Y et al. Harmful effects of NSAIDs among patients with hypertension and coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2011; 124:614-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21596367 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4664475/

1200. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA drug safety communication: FDA recommends avoiding use of NSAIDs in pregnancy at 20 weeks or later because they can result in low amniotic fluid. 2020 Oct 15. From the FDA website. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-recommends-avoiding-use-nsaids-pregnancy-20-weeks-or-later-because-they-can-result-low-amniotic

1201. Avet Pharmaceuticals. Diflunisal tablets prescribing information. East Brunswick, NJ; 2020 Nov.

1202. Actavis Pharma. Sulindac tablets prescribing information. Parsippany, NJ; 2020 Oct.

1203. Jubilant Cadista Pharmaceuticals. Indomethacin extended-release capsules prescribing information. Salisbury, MD; 2020 Nov.

Related/similar drugs

More about diflunisal

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (8)

- Drug images

- Latest FDA alerts (4)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Breastfeeding

- En español