Ampicillin (Monograph)

Drug class: Aminopenicillins

Chemical name: [2S-[2α,5α,6β(S*)]]-6-[(Aminophenylacetyl)amino]-3,3-dimethyl-7-oxo-4-thia-1-azabicyclo[3.2.0]heptane-2-carboxylic acid

Molecular formula: C16H19N3O4SC16H19N3O4S•NaC16H19N3O4S•3H2O

CAS number: 69-53-4

Introduction

Antibacterial; β-lactam antibiotic; aminopenicillin.1 2 8 9

Uses for Ampicillin

Endocarditis

Treatment of enterococcal endocarditis;2 4 6 7 used in conjunction with an aminoglycoside.4 6 7

Treatment of endocarditis caused by susceptible staphylococci, streptococci, E. coli, P. mirabilis, or Salmonella.2

For treatment of endocarditis caused by Enterococcus faecalis, E. faecium, or other enterococci susceptible to penicillin and gentamicin, AHA states IV penicillin G (or IV ampicillin) in conjunction with gentamicin is a regimen of choice;6 7 streptomycin can be substituted for gentamicin if enterococci are susceptible to penicillin and streptomycin, but resistant to gentamicin.6

For treatment of endocarditis caused by viridans group streptococci† [off-label] or nonenterococcal group D streptococci† [off-label], including Streptococcus gallolyticus† [off-label] (formerly S. bovis), AHA states that IV ampicillin is a reasonable alternative to IV penicillin G.6 May be used alone if caused by highly penicillin-susceptible strains (penicillin MIC ≤0.12 mcg/mL);6 use in conjunction with gentamicin if strains are relatively resistant (penicillin MIC >0.12 mcg/mL but <0.5 mcg/mL).6

Because fastidious gram-negative bacilli of the HACEK group† [off-label] (i.e., Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella) resistant to penicillins are being reported with increasing frequency, AHA states that IV ampicillin (with or without an aminoglycoside) should be used for the treatment of endocarditis caused by these organisms only if in vitro susceptibility is confirmed.6 7

Consult current guidelines from AHA for information on management of endocarditis.6 7

Prevention of α-hemolytic (viridans group) streptococcal bacterial endocarditis† [off-label] in patients undergoing certain dental procedures (i.e., procedures that involve manipulation of gingival tissue or periapical region of teeth or perforation of oral mucosa) or certain invasive respiratory tract procedures (i.e., procedures involving incision or biopsy of respiratory mucosa) who have certain cardiac conditions that put them at highest risk of adverse outcomes from endocarditis.451 AHA recommends oral amoxicillin as drug of choice; ampicillin is an alternative in those unable to take oral medication.451

Consult most recent AHA recommendations for information on which cardiac conditions are associated with highest risk of adverse outcomes from endocarditis and specific recommendations regarding use of prophylaxis to prevent endocarditis in these patients.451

Meningitis and Other CNS Infections

Treatment of meningitis caused by susceptible Neisseria meningitidis,2 5 418 Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococci; GBS),2 5 418 Listeria monocytogenes,2 4 5 418 E. coli,2 5 or H. influenzae†.5 416

A drug of choice for empiric treatment of neonatal S. agalactiae meningitis;5 418 consider concomitant use of an aminoglycoside.418

A drug of choice for L. monocytogenes meningitis;4 5 9 418 used alone or in conjunction with an aminoglycoside (e.g., gentamicin).4 5 9 418

Respiratory Tract Infections

Treatment of respiratory tract infections caused by susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (including penicillinase-producing strains), Streptococcus (including S. pneumoniae), S. pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic streptococci), or H. influenzae (nonpenicillinase-producing strains only).1 2 9

Generally should not be used for the treatment of streptococcal or staphylococcal infections when a natural penicillin would be effective.4 5 8 9 Should not be used alone for empiric treatment of respiratory tract infections when ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae may be involved.5 9

Septicemia

Treatment of septicemia caused by susceptible staphylococci, streptococci, enterococci, E. coli, P. mirabilis, or Salmonella.2 9

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Treatment of UTIs caused by susceptible enterococci, E. coli, or Proteus mirabilis.1 2 9

A drug of choice for enterococcal UTIs.4 9 Because of high urinary concentrations, may be effective when used alone,9 but consider that enterococci resistant to ampicillin have been reported.4

Eikenella Infections

Treatment of infections caused by Eikenella corrodens†; drug of choice.4

Listeria Infections

Treatment of infections caused by Listeria monocytogenes; used alone or in conjunction with an aminoglycoside.5 9

A drug of choice for Listeria infections occurring during pregnancy, granulomatosis infantiseptica, sepsis, endocarditis, meningitis, and foodborne infections.4 5 9 9 (See Meningitis and Other CNS Infections under Uses.)

Pertussis

Has been used to treat and prevent secondary pulmonary infections in patients with pertussis†.9 Erythromycin generally considered drug of choice for treatment of catarrhal stage of pertussis and to shorten the period of communicability of the disease.5 9 Ampicillin, like most other anti-infectives, does not shorten clinical course of pertussis.9

Typhoid Fever and Other Salmonella Infections

Alternative for treatment of typhoid fever (enteric fever) caused by susceptible Salmonella typhi.2 4 5 9 Drugs of choice are third generation cephalosporins (e.g., ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) or fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin);4 consider that multidrug-resistant strains of S. typhi (strains resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, and/or co-trimoxazole) reported with increasing frequency.5

Treatment of chronic carriers of S. typhi†; drugs of choice are fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin), ampicillin, or amoxicillin (with probenecid).5 8 9

Treatment of gastroenteritis caused by susceptible Salmonella.2 4 5

Shigella Infections

Treatment of GI infections caused by susceptible Shigella.1 2 5 9

Anti-infectives generally indicated in addition to fluid and electrolyte replacement for severe shigellosis.5 9 Previously considered a drug of choice for shigellosis (especially in children),9 but strains of S. flexneri and S. sonnei resistant to ampicillin reported with increasing frequency.9 Fluoroquinolones, ceftriaxone, or co-trimoxazole now considered drugs of choice for empiric treatment,4 5 9 especially in areas where ampicillin-resistant strains of Shigella have been reported.5 9

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease

Prevention of early-onset neonatal group B streptococcal (GBS) disease†.292 359

ACOG, AAP, and others recommend routine universal prenatal screening for GBS colonization (e.g., vaginal and rectal cultures) in all pregnant women at 36 through 37 weeks of gestation (i.e., performed within the time period of 36 weeks 0 days to 37 weeks 6 days of gestation), unless intrapartum anti-infective prophylaxis already planned because the woman had known GBS bacteriuria during any trimester of current pregnancy or has history of a previous infant with GBS disease.292 359 Anti-infective prophylaxis for prevention of early-onset perinatal GBS indicated in all women identified as having positive GBS cultures during routine prenatal GBS screening during current pregnancy, unless a cesarean delivery is performed before onset of labor in the setting of intact membranes.292 359 Also indicated in women with unknown GBS status at time of onset of labor (cultures not performed or results unknown) who have risk factors for perinatal GBS infection (e.g., preterm birth at <37 weeks’ gestation, duration of membrane rupture ≥18 hours, intrapartum fever ≥38°C).292 359

IV penicillin G is drug of choice and IV ampicillin is preferred alternative for intrapartum GBS anti-infective prophylaxis.292 359 Penicillin G has a narrower spectrum of activity and is less likely to select for antibiotic-resistant organisms.292 359

Regardless of whether the mother received anti-infective prophylaxis, initiate appropriate diagnostic evaluations and anti-infective therapy in the neonate if signs or symptoms of active infection develop.292 359

Consult current ACOG guidelines available at [Web] for additional information regarding prevention of neonatal early-onset GBS disease.359

Ampicillin Dosage and Administration

Administration

Administer orally,1 by slow IV injection or infusion,2 or by IM injection.2

Oral Administration

Administer orally with a full glass of water 1 hour before or 2 hours after meals.1

IV Administration

For solution and drug compatibility information, see Compatibility under Stability.

Reconstitution

Reconstitute vials containing 125, 250, or 500 mg with 5 mL of sterile or bacteriostatic water for injection.2 Alternatively, reconstitute vials containing 1 or 2 g with 7.4 or 14.8 mL, respectively, of sterile or bacteriostatic water for injection.2

Rate of Administration

Solutions reconstituted from 125-, 250-, or 500-mg vials may be given by IV injection over a period of 3–5 minutes.2 Solutions reconstituted from 1- or 2-g vials should be given IV over a period of ≥10–15 minutes.2

For IV infusion, concentration and rate of administration should be adjusted so that the total dose is administered before the drug is inactivated in the IV solution.2

IM Administration

Reconstitution

Reconstitute with sterile or bacteriostatic water for injection according to manufacturer’s directions to provide solutions containing 125 or 250 mg/mL.2

Dosage

Available as ampicillin trihydrate1 and ampicillin sodium2 ; dosage expressed in terms of ampicillin.1 2

Duration of therapy depends on type and severity of infection and should be determined by clinical and bacteriologic response of the patient.1 2 For most infections, therapy should be continued for ≥48–72 hours after patient becomes asymptomatic or evidence of eradication of the infection has been obtained.1 2 More prolonged therapy may be necessary for some infections.1 2

Pediatric Patients

General Pediatric Dosage

Oral

Children beyond neonatal age with mild to moderate infections: AAP recommends 50–100 mg/kg daily given in 4 divided doses.292

Children beyond neonatal age with severe infections: AAP states oral route inappropriate.292

IV or IM

Neonates <7 days of age: AAP recommends 50 mg/kg every 12 hours in those weighing ≤2 kg or 50 mg/kg every 8 hours in those weighing >2 kg.292 Higher dosage may be needed for treatment of meningitis.292

Neonates 8–28 days of age: AAP recommends 50 mg/kg every 8 hours in those weighing ≤2 kg or 50 mg/kg every 6 hours in those weighing >2 kg.292 Higher dosage may be needed for treatment of meningitis.292

Children beyond neonatal age: AAP recommends 100–150 mg/kg daily given in 4 divided doses for mild to moderate infections or 200–400 mg/kg daily given in 4 divided doses for severe infections.292 Use highest dosage for treatment of CNS infections.292

Endocarditis

Treatment of Endocarditis Caused by Viridans Streptococci or S. bovis

IV200–300 mg/kg daily (up to 12 g daily) given in 4–6 divided doses for 4 weeks.7 Used in conjunction with IM or IV gentamicin.7

Treatment of Enterococcal Endocarditis

IV200–300 mg/kg daily (up to 12 g daily) given in 4–6 divided doses for 4–6 weeks.7 Used in conjunction with IM or IV gentamicin.7

Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis in Patients Undergoing Certain Dental or Respiratory Tract Procedures†

IV or IM50 mg/kg as a single dose given 30–60 minutes prior to the procedure.451

GI Infections

Oral

Children weighing ≤20 kg: 100 mg/kg daily in 4 divided doses.1

Children weighing >20 kg: 500 mg 4 times daily.1 Severe or chronic infections may require higher dosage.1

IV or IM

Children weighing <40 kg: 50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 500 mg every 6 hours.2 Severe or chronic infections may require higher dosage.1

Meningitis and Other CNS Infections

Empiric Treatment of Meningitis

IVNeonates and children <2 months of age: 100–300 mg/kg daily given in divided doses; with or without gentamicin.986 1414 1647

Children 2 months to 12 years of age: 200–400 mg/kg daily given in divided doses every 4–6 hours; used in conjunction with IV chloramphenicol.986 1414 1647

Treatment of Meningitis Caused by S. agalactiae (GBS)

IVNeonates: AAP recommends 200–300 mg/kg daily given in 3 divided doses in those ≤7 days of age or 300 mg/kg daily given in 4 divided doses in those >7 days of age.292

Neonates ≤28 days of age: Some experts recommend 75 mg/kg every 6 hours, regardless of weight.292

Respiratory Tract Infections

Oral

Children weighing ≤20 kg: 50 mg/kg daily in 3 or 4 divided doses.1

Children weighing >20 kg: 250 mg 4 times daily.1

IV or IM

Children weighing <40 kg: 25–50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 250–500 mg every 6 hours.2

Septicemia

IV or IM

150–200 mg/kg daily.2

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

IV or IM

Children weighing <40 kg: 25–50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 250–500 mg every 6 hours.2

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Oral

Children weighing ≤20 kg: 100 mg/kg daily in 4 divided doses.1

Children weighing >20 kg: 500 mg 4 times daily.1 Severe or chronic infections may require higher dosage.1

IV or IM

Children weighing <40 kg: 50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Children weighing ≥40 kg: 500 mg every 6 hours.2 Severe or chronic infections may require higher dosage.1

Adults

Endocarditis

Treatment of Enterococcal Endocarditis

IV2 g every 4 hours in conjunction with IM or IV gentamicin.6 Treatment with both drugs generally should be continued for 4–6 weeks, but patients who had symptoms of infection for >3 months before treatment was initiated and patients with prosthetic heart valves require ≥6 weeks of therapy with both drugs.6

Treatment of Endocarditis Caused by HACEK group (i.e., Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium hominis, Eikenella corrodens, Kingella)†

IV2 g every 12 hours.6

Prevention of Bacterial Endocarditis in Patients Undergoing Certain Dental or Respiratory Tract Procedures†

IV or IM2 g as a single dose given 30–60 minutes prior to the procedure.451

GI Infections

Oral

500 mg 4 times daily.1

IV or IM

Adults weighing <40 kg: 50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Adults weighing ≥40 kg: 500 mg every 6 hours.2

Meningitis and Other CNS Infections

IV, then IM

150–200 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 3–4 hours.2 Use IV initially, may switch to IM after 3 days.2

Respiratory Tract Infections

Oral

250 mg 4 times daily.1

IV or IM

Adults weighing <40 kg: 25–50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Adults weighing ≥40 kg: 250–500 mg every 6 hours.2

Septicemia

IV or IM

150–200 mg/kg daily.2

Skin and Skin Structure Infections

IV or IM

Adults weighing <40 kg: 25–50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Adults weighing ≥40 kg: 250–500 mg every 6 hours.2

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs)

Oral

500 mg 4 times daily.1

IV or IM

Adults weighing <40 kg: 50 mg/kg daily in divided doses every 6–8 hours.2

Adults weighing ≥40 kg: 500 mg every 6 hours.2

Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal (GBS) Disease†

IV

An initial 2-g dose (at time of labor or rupture of membranes) followed by 1 g every 4 hours until delivery.292 359

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Pediatric dosage should not exceed adult dosage.1

Special Populations

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustments necessary in patients with renal impairment.9 1373

Some clinicians suggest that adults with GFR 10–50 mL/minute receive the usual dose every 6–12 hours and that adults with GFR <10 mL/minute receive the usual dose every 12–16 hours.1373 Alternatively, some clinicians suggest that modification of usual dosage is unnecessary in adults with Clcr ≥ 30 mL/minute, but that adults with Clcr ≤10 mL/minute should receive the usual dose every 8 hours.1373

Patients undergoing hemodialysis should receive a supplemental dose after each dialysis period.1373

Geriatric Patients

No dosage adjustments except those related to renal impairment. (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Cautions for Ampicillin

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Superinfection/Clostridioides difficile-associated Colitis

Possible emergence and overgrowth of nonsusceptible bacteria or fungi.1 2 Discontinue and institute appropriate therapy if superinfection occurs.1 2

Treatment with anti-infectives alters normal colon flora and may permit overgrowth of C. difficile.1 302 C. difficile infection (CDI) and C. difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis (CDAD; also known as antibiotic-associated diarrhea and colitis or pseudomembranous colitis) reported with nearly all anti-infectives and may range in severity from mild diarrhea to fatal colitis.302 Consider CDAD if diarrhea develops during or after therapy and manage accordingly.1 302

If CDAD suspected or confirmed, discontinue anti-infectives not directed against C. difficile as soon as possible.302 Initiate appropriate anti-infective therapy directed against C. difficile (e.g., fidaxomicin, vancomycin, metronidazole), appropriate supportive therapy (e.g., fluid and electrolyte management, protein supplementation), and surgical evaluation as clinically indicated.1 302

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Serious and occasionally fatal hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, reported with penicillins.1 2 9

Prior to initiation of therapy, make careful inquiry regarding previous hypersensitivity reactions to penicillins, cephalosporins, or other drugs.1 2 Partial cross-allergenicity occurs among penicillins and other β-lactam antibiotics including cephalosporins and cephamycins.1 2

If a severe hypersensitivity reaction occurs, discontinue immediately and institute appropriate therapy as indicated (e.g., epinephrine, corticosteroids, maintenance of an adequate airway and oxygen).1 2

General Precautions

Selection and Use of Anti-infectives

To reduce development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain effectiveness of ampicillin and other antibacterials, use only for treatment or prevention of infections proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria.

When selecting or modifying anti-infective therapy, use results of culture and in vitro susceptibility testing.1 2 In the absence of such data, consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns when selecting anti-infectives for empiric therapy.1 2

Mononucleosis

Possible increased risk of rash in patients with mononucleosis; use in these patients not recommended.9

Ampicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae

Because of increasing prevalence of ampicillin-resistant H. influenzae,5 the drug should not be used alone for empiric treatment of serious infections (e.g., meningitis, pneumonia) when H. influenzae may be involved.5 9

Laboratory Monitoring

Periodically assess organ system functions, including renal, hepatic, and hematopoietic, during prolonged therapy.1 2

Sodium Content

Powder for injection contains 2.9 mEq of sodium per g of ampicillin.2

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 2 9 Use with caution.1 2

Pediatric Use

Renal clearance of ampicillin may be delayed in neonates and young infants because of incompletely developed renal function.1 9 Use lowest effective dosage.1

Renal Impairment

Dosage adjustments necessary in renal impairment.9 1373 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.)

Common Adverse Effects

GI effects (diarrhea, nausea),9 rash.9

Drug Interactions

Specific Drugs and Laboratory Tests

|

Drug or Test |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Allopurinol |

Clinical importance has not been determined;1153 some clinicians suggest that concomitant use of the drugs should be avoided if possible712 |

|

|

Aminoglycosides |

In vitro evidence of synergistic antibacterial effects against enterococci;80 116 282 used to therapeutic advantage in treatment of endocarditis and other severe enterococcal infections6 7 Potential in vitro and in vivo inactivation of aminoglycosidesHID |

|

|

Chloramphenicol |

Clinical importance unclear |

|

|

Hormonal contraceptives |

Possible decreased efficacy of estrogen-containing oral contraceptives and increased incidence of breakthrough bleeding771 772 1043 1153 |

Some clinicians suggest that a supplemental method of contraception be used in patients receiving oral contraceptives and ampicillin concomitantly, other clinicians state that most women taking oral contraceptives probably do not need to use alternative contraceptive precautions while receiving ampicillin771 772 1043 1044 |

|

Methotrexate |

Possible decreased renal clearance of methotrexate with penicillins; possible increased methotrexate concentrations and hematologic and GI toxicity1408 |

Monitor closely if used concomitantly1408 |

|

Probenecid |

Decreased renal tubular secretion of ampicillin; increased and prolonged ampicillin concentrations may occur9 |

|

|

Sulbactam |

Synergistic bactericidal effect against many strains of β-lactamase-producing bacteria1903 1954 1955 |

|

|

Sulfonamides |

In vitro evidence of antagonism1 |

Clinical importance unclear1 |

|

Tests for glucose |

Possible false-positive reactions in urine glucose tests using Clinitest, Benedict’s solution, or Fehling’s solution1 2 |

Use glucose tests based on enzymatic glucose oxidase reactions (e.g., Clinistix, Tes-Tape)1 2 |

|

Tests for uric acid |

Possible falsely increased serum uric acid concentrations when copper-chelate method is used;800 phosphotungstate and uricase methods appear to be unaffected by the ampicillin800 |

Ampicillin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

30–55% of an oral dose absorbed from the GI tract in fasting adults;320 366 494 peak serum concentrations attained within 1–2 hours.9 443 512

Following IM administration, peak serum concentrations generally attained more quickly and are higher than following equivalent oral doses.9 338 404 453

Food

Food generally decreases rate and extent of absorption.9 342 457 466

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into ascitic,339 synovial,323 326 335 and pleural435 fluids. Also distributed into liver,495 511 lungs,495 gallbladder,483 495 prostate,332 muscle,492 middle ear effusions,333 431 511 1171 bronchial secretions,333 432 1171 maxillary sinus secretions.599 and tonsils.333 431 511 1171

Distributed into CSF in concentrations 11–65% of simultaneous serum concentrations;1423 highest CSF concentrations occur 3–7 hours after an IV dose.1423

Readily crosses the placenta.9 320 467 Distributed into milk in low concentrations.355 1568

Plasma Protein Binding

Protein binding is lower in neonates than in children or adults;340 ampicillin reportedly 8–12% bound to serum proteins in neonates.340

Elimination

Metabolism

Partially metabolized by hydrolysis of the β-lactam ring to penicilloic acid which is microbiologically inactive.9

Elimination Route

Eliminated in urine by renal tubular secretion and to a lesser extent by glomerular filtration.9 Small amounts also excreted in feces and bile.9

In adults with normal renal function, approximately 20–64% of a single oral dose9 336 351 443 479 493 excreted unchanged in urine within 6–8 hours. Approximately 60–70% of a single IM dose336 337 or 73–90% of a single IV dose490 excreted unchanged in urine.

Half-life

0.7–1.5 hours in adults with normal renal function.9 320 348

Half-life is 4 hours in neonates 2–7 days of age, 2.8 hours in neonates 8–14 days of age, and 1.7 hours in neonates 15–30 days of age.9

Special Populations

Serum concentrations higher and more prolonged in premature or full-term neonates <6 days of age than in full-term neonates ≥6 days of age.340 358 444 470 484

Renal clearance decreased in geriatric patients because of diminished tubular secretory ability; serum concentrations may be higher and half-life prolonged.482 In those 67–76 years of age, half-life ranges from 1.4–6.2 hours.482

Serum concentrations are higher and half-life prolonged in patients with impaired renal function.320 328 348 Half-life may range from 7.4–21 hours in patients with Clcr <10 mL/minute.9 320 348

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

Tight container at 15–30°C; avoid excessive heat.1

For Suspension

Tight container at 15–30°C.1 After reconstitution, discard after 7 days if stored at room temperature or after 14 days if refrigerated.1

Parenteral

Powder for Injection or Infusion

Solutions for IM injection or IV injection or infusion should be used within 1 hour after reconstitution and should not be frozen.2

Compatibility

Parenteral

Solution CompatibilityHID

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Isolyte M or P with dextrose 5% |

|

Incompatible |

|

Amino acids 4.25%, dextrose 25% |

|

Dextran 40 10% in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Dextran 40 10% in dextrose 5% in water |

|

Dextrose 5% in sodium chloride 0.45 or 0.9% |

|

Dextrose 5 or 10% in water |

|

Fat emulsion 10%, IV |

|

Fructose 5.25% |

|

Hetastarch 6% in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Ringer’s injection, lactated |

|

Sodium bicarbonate 1.4% |

|

Sodium lactate (1/6) M |

|

Variable |

|

Ringer’s injection |

|

Sodium chloride 0.9% |

Drug Compatibility

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Clindamycin phosphate |

|

Erythromycin lactobionate |

|

Furosemide |

|

Lincomycin HCl |

|

Metronidazole |

|

Incompatible |

|

Amikacin sulfate |

|

Chlorpromazine HCl |

|

Dopamine HCl |

|

Gentamicin sulfate |

|

Hetastarch in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Hydralazine HCl |

|

Prochlorperazine mesylate |

|

Variable |

|

Aztreonam |

|

Cefepime HCl |

|

Heparin sodium |

|

Hydrocortisone sodium succinate |

|

Ranitidine HCl |

|

Verapamil HCl |

|

Compatible |

|---|

|

Acyclovir sodium |

|

Alprostadil |

|

Amifostine |

|

Anidulafungin |

|

Aztreonam |

|

Bivalirudin |

|

Cyclophosphamide |

|

Dexmedetomidine HCl |

|

Docetaxel |

|

Doxapram HCl |

|

Doxorubicin HCl liposome injection |

|

Enalaprilat |

|

Esmolol HCl |

|

Etoposide phosphate |

|

Famotidine |

|

Filgrastim |

|

Fludarabine phosphate |

|

Foscarnet sodium |

|

Gemcitabine HCl |

|

Granisetron HCl |

|

Heparin sodium |

|

Heparin sodium with hydrocortisone sodium succinate |

|

Hetastarch in lactated electrolyte injection (Hextend) |

|

Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Insulin, regular |

|

Labetalol HCl |

|

Levofloxacin |

|

Linezolid |

|

Magnesium sulfate |

|

Melphalan HCl |

|

Meperidine HCl |

|

Milrinone lactate |

|

Morphine sulfate |

|

Multivitamins |

|

Pantoprazole sodium |

|

Pemetrexed disodium |

|

Phytonadione |

|

Potassium chloride |

|

Propofol |

|

Remifentanil HCl |

|

Tacrolimus |

|

Teniposide |

|

Theophylline |

|

Thiotepa |

|

Incompatible |

|

Amphotericin B cholesteryl sulfate complex |

|

Caspofungin acetate |

|

Epinephrine HCl |

|

Fenoldopam mesylate |

|

Fluconazole |

|

Hydralazine HCl |

|

Midazolam HCl |

|

Nicardipine HCl |

|

Ondansetron HCl |

|

Sargramostim |

|

Verapamil HCl |

|

Vinorelbine tartrate |

|

Variable |

|

Calcium gluconate |

|

Cisatracurium besylate |

|

Diltiazem HCl |

|

Hetastarch in sodium chloride 0.9% |

|

Hydromorphone HCl |

|

Vancomycin HCl |

Actions and Spectrum

-

Based on spectrum of activity, classified as an aminopenicillin.8 9 Aminopenicillins have enhanced activity against gram-negative bacteria compared with natural and penicillinase-resistant penicillins.8 9

-

Like other β-lactam antibiotics, antibacterial activity results from inhibition of bacterial cell wall synthesis.1 2

-

Spectrum of activity includes many gram-positive and -negative aerobes and some anaerobes.1 9 12

-

Gram-positive aerobes: active in vitro and in clinical infections against Staphylococcus (β-lactamase-negative strains only), Streptococcus pneumoniae, other Streptococcus (α- and β-hemolytic strains only), and Enterococcus faecalis.1 9 12 Also active against Corynebacteriun and Listeria monocytogenes.1 9 12

-

Gram-negative aerobes: active in vitro and in clinical infections against H. influenzae, N. gonorrhoeae, E. coli, Proteus mirabilis, Salmonella, and Shigella.1 9 12 Also active in vitro against Bordetella pertussis, Eikenella corrodens, and Neisseria meningitidis.9 Inactive against Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Providencia, and Serratia.9 12

-

Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria that produce β-lactamases, including β-lactamase-producing S. aureus and E. faecalis, are resistant.9 12

-

Complete cross-resistance generally occurs between ampicillin and amoxicillin.9

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients that antibacterials (including ampicillin) should only be used to treat bacterial infections and not used to treat viral infections (e.g., the common cold).

-

Importance of completing the entire prescribed course of treatment, even if feeling better after a few days.

-

Advise patients that skipping doses or not completing the full course of therapy may decrease effectiveness and increase the likelihood that bacteria will develop resistance and will not be treatable with ampicillin or other antibacterials in the future.

-

Importance of taking oral ampicillin with a full glass of water 1 hour before or 2 hours after a meal.1

-

Importance of discontinuing therapy and informing clinician if an allergic reaction occurs.1

-

Importance of informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs.1

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

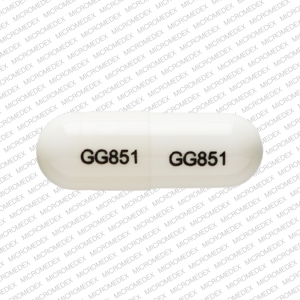

Oral |

Capsules |

250 mg (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Capsules |

|

|

500 mg (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Capsules |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Parenteral |

For injection |

125 mg (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|

|

250 mg (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|||

|

500 mg (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|||

|

1 g (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|||

|

2 g (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|||

|

10 g (of ampicillin) pharmacy bulk package* |

Ampicillin Sodium for Injection |

|||

|

For injection, for IV infusion |

1 g (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium ADD-Vantage |

||

|

Ampicillin Sodium Piggyback |

||||

|

2 g (of ampicillin)* |

Ampicillin Sodium ADD-Vantage |

|||

|

Ampicillin Sodium Piggyback |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions February 2, 2022. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Apothecon. Principen (ampicillin) capsules and powder for oral suspension prescribing information. Princeton, NJ; 1997 Mar.

2. Apothecon. Sterile ampicillin sodium, USP for intramuscular or intravenous injection prescribing information. Princeton, NJ; 1996 May.

4. Anon. The choice of antibacterial drugs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2001; 43:69-78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11518876

5. Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Red book: 2000 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000.

6. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015; 132:1435-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26373316

7. Baltimore RS, Gewitz M, Baddour LM et al. Infective Endocarditis in Childhood: 2015 Update: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015; 132:1487-515. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26373317

8. Chambers HF. Penicillins. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 5th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000: 261-74.

9. Kucers A, Crowe S, Grayson ML et al, eds. The use of antibiotics. A clinical review of antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral drugs. 5th ed. Jordan Hill, Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997: 108-33,209-19.

11. Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015; 64(RR-03):1-137. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26042815

12. AHFS Drug Information 2004. McEvoy GK, ed. Aminopenicillins General Statement. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2004:293-308.

80. Barza M. Antimicrobial spectrum, pharmacology and therapeutic use of antibiotics. Part 2: penicillins. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1977; 34:57-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/318800

116. Lorian V, ed. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1980:298-341, 418-73, 607-722.

282. Serra P, Brandimarte C, Martino P et al. Synergistic treatment of enterococcal endocarditis: in vitro and in vivo studies. Arch Intern Med. 1977; 137:1562-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/921443

292. American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015.

302. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018; 66:987-994. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29562266

305. Feldman WE, Zweighaft T. Effect of ampicillin and chloramphenicol againstStreptococcus pneumoniaeandNeisseria meningitidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979; 15:240-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352639/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34360

306. Rocco V, Overturf G. Chloramphenicol inhibition of the bactericidal effect of ampicillin againstHaemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982; 21:349-51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC181888/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6978674

320. Barza M, Weinstein L. Pharmacokinetics of the penicillins in man. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1976; 1:297-308. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/797501

323. Nelson JD, Howard JB, Shelton S. Oral antibiotic therapy for skeletal infections of children. J Pediatr. 1978; 92:131-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/619055

326. Nelson JD. Antibiotic concentrations in septic joint effusions. N Engl J Med. 1971; 284:349-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5539915

328. Ruedy J. The effects of peritoneal dialysis on the physiological disposition of oxacillin, ampicillin and tetracycline in patients with renal disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1966; 94:257-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1935278/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5903164

332. Madsen PO, Kjaer TB, Baumueller A et al. Antimicrobial agents in prostatic fluid and tissue. Infection. 1976; 4(Suppl 2):S154-8.

333. Bergogne-Berezin E, Morel C, Benard Y et al. Pharmacokinetic study of β-lactam antibiotics in bronchial secretions. Scand J Infect Dis. 1978; 14(Suppl):267-72.

335. Howall A, Sutherland R, Rolinson GN. Effect of protein binding on levels of ampicillin and cloxacillin in synovial fluid. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1972; 13:724-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5053814

336. Kunin CM. Clinical pharmacology of the new penicillins: the importance of serum protein binding in determining antimicrobial activity and concentrations in serum. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1966; 7:166-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4956690

337. Kunin CM. Clinical significance of protein binding of the penicillins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1967; 145:282-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4998178

338. Bergan T, Oydvin B. Cross-over study of penicillin pharmacokinetics after intravenous infusions. Chemotherapy. 1974; 20:263-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4412673

339. Gerding DN, Hall WH, Schierl EA. Antibiotic concentrations in ascitic fluid of patients with ascites and bacterial peritonitis. Ann Intern Med. 1977; 86:708-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/869351

340. Morselli PL, Franco-Morselli R, Bossi L. Clinical pharmacokinetics in newborns and infants: age-related differences and therapeutic implications. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1980; 5:485-527. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7002417

342. Melander A. Influence of food on the bioavailability of drugs.Clin Pharmacokinet. 1978:3:337-51.

348. Giusti DL. A review of the clinical use of antimicrobial agents in patients with renal and hepatic insufficiency: the penicillins. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1973; 7:62-74.

351. Rozencweig M, Staquet M, Klastersky J. Antibacterial activity and pharmacokinetics of bacampicillin and ampicillin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1976; 19:592-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6181

355. Anderson PO. Drugs and breast feeding—a review. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1977; 11:208-23.

358. Cohen MD, Raeburn JA, Devine J et al. Pharmacology of some oral penicillins in the newborn infant. Arch Dis Child. 1975; 50:230-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1544517/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1147656

359. . Prevention of Group B Streptococcal Early-Onset Disease in Newborns: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 797. Obstet Gynecol. 2020; 135:e51-e72. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/02/prevention-of-group-b-streptococcal-early-onset-disease-in-newborns https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31977795

366. Cole M, Kening MD, Hewitt VA. Metabolism of penicillins to penicilloic acids and 6-aminopenicillanic acid in man and its significance in assessing penicillin absorption. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1973; 3:463-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC444435/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4364176

404. Doluisio JT, LaPiana JC, Dittert LW. Pharmacokinetics of ampicillin trihydrate, sodium ampicillin, and sodium dicloxacillin following intramuscular injection. J Pharm Sci. 1971; 60:715-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5125769

416. Tunkel AR, Hasbun R, Bhimraj A et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America's Clinical Practice Guidelines for Healthcare-Associated Ventriculitis and Meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017; 64:e34-e65. Updates may be available at IDSA website at www.idsociety.org. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28203777

418. Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL et al. Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004; 39:1267-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15494903

431. Davies B, Maesen F. Serum and sputum antibiotic levels after ampicillin, amoxycillin and bacampicillin in chronic bronchitis patients. Infection. 1979; 7(Suppl 5):S465-8.

432. Bergogne-Berezin E, Berthelot G, Kafe H et al. Penetration of ampicillin into human bronchial secretions. Infection. 1979; 7(Suppl 5):S463-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/511358

435. Daschner FD, Gier E, Lentzen H et al. Penetration into the pleural fluid after bacampicillin and amoxycillin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981; 7:585-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7263554

443. Tan JS, Salstrom SJ. Bacampicillin, ampicillin, cephalothin, and cephapirin levels in human blood and interstitial fluid. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979; 15:510-2. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352701/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/464583

444. Rudoy RC, Goto N, Pettit D et al. Pharmacokinetics of intravenous amoxicillin in pediatric patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979; 15:628-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352722/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/464594

451. Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007; 116:1736-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17446442

453. Bergan T. Pharmacokinetic comparison of oral bacampicillin and parenteral ampicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978; 13:971-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352373/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/677863

457. Eshelman FN, Spyker DA. Pharmacokinetics of amoxicillin and ampicillin: crossover study of the effect of food. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978; 14:539-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC352504/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/363052

466. Welling PG, Huang H, Kock PA et al. Bioavailability of ampicillin and amoxicillin in fasted and nonfasted subject. J Pharm Sci. 1977; 66:549-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/323461

467. Kraybill EN, Chaney NE, McCarthy LR. Transplacental ampicillin: inhibitory concentrations in neonatal serum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1980; 138:793-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7446612

470. Driessen OM, Sorgedrager N, Michel MF et al. Pharmacokinetic aspects of therapy with ampicillin and kanamycin in new-born infants. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1978; 13:449-57.

479. Gordon RC, Regamey C, Kirby WM. Comparative clinical pharmacology of amoxicillin and ampicillin administered orally. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1972; 1:504-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC444250/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4680813

482. Triggs EJ, Johnson JM, Learoyd B. Absorption and disposition of ampicillin in the elderly. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1980; 18:195-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7428803

483. Ingold A. Sputum and serum levels of amoxycillin in chronic bronchial infections. Br J Dis Chest. 1975; 69:211-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1201187

484. Driessen OM, Sorgedrager N, Michel MF et al. Variability and predictability of the plasma concentration of ampicillin and kanamycin in new-born infants. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1979; 15:133-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/436921

490. Jusko WJ, Lewis GP. Comparison of ampicillin and hetacillin pharmacokinetics in man. J Pharm Sci. 1973; 62:69-76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4630199

492. Vitti TG, Gurwith MJ, Ronald AR. Pharmacologic studies of amoxicillin in nonfasting adults. J Infect Dis. 1974; 129(Suppl):S149-53.

493. Kirby WM, Gordon RC, Regamey C. The pharmacology of orally administered amoxicillin and ampicillin. J Infect Dis. 1974; 129(Suppl):S154-5.

494. Lode H, Janisch P, Kupper G et al. Comparative clinical pharmacology of three ampicillins and amoxicillin administered orally. J Infect Dis. 1974; 129(Suppl):S156-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4834960

495. Kiss IJ, Farago E, Schnitzler J et al. Amoxycillin levels in human serum, bile, gallbladder, lung, and liver tissue. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1981; 19:69-74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7216553

511. Klimek JJ, Nightingale C, Lehmann WB et al. Comparison of concentrations of amoxicillin and ampicillin in serum and middle ear fluid of children with chronic otitis media. J Infect Dis. 1977; 135:999-1002. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/864293

512. Ridley M. Hetacillin and ampicillin. Br Med J. 1967; 2:305. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1841869/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20791237

599. Ekedahl C, Holm SE, Bergholm AM. Penetration of antibiotics into the normal and diseased maxillary sinus mucosa. Scand J Infect Dis. 1978; 14(Suppl):279-84.

712. Murphy TF. Ampicillin rash and hyperuricemia. Ann Intern Med. 1979; 91:324. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/157097

771. Friedman DI, Huneke AL, Kim MH et al. The effect of ampicillin on oral contraceptive effectiveness. Obstet Gynecol. 1980; 55:33-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7188714

772. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, MacIver M et al. The interaction between ampicillin and oral contraceptive steroids in women.Proc Br Pharmacol Soc. 1981; 280-1.

774. Jick H, Porter JB. Potentiation of ampicillin skin reactions by allopurinol or hyperuricemia. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981; 21:456-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6458626

800. Lum G, Gambino SR. Comparison of four methods for measuring uric acid: copper-chelate, phosphotungstate, manual uricase, and automated kinetic uricase. Clin Chem. 1973; 19:1184-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4741958

829. Jick H, Slone D, Shapiro S et al. Excess of ampicillin rashes associated with allopurinol or hyperuricemia. N Engl J Med. 1972; 286:505-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4258181

986. Bell WE. Treatment of bacterial infections of the central nervous system. Ann Neurol. 1981; 9:313-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7013653

1043. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, Crawford FE et al. Interindividual variation and drug interactions with hormonal steroid contraceptives. Drugs. 1981; 21:46-61. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7009137

1044. Back DJ, Breckenridge AM, MacIver M et al. The effects of ampicillin on oral contraceptive steroids in women. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 14:43-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1427567/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6809025

1153. Hansten PD. Drug interactions. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1979:130, 133, 141, 143, 155, 156.

1171. Wong GA, Pierce TH, Goldstein E et al. Penetration of antimicrobial agents into bronchial secretions. Am J Med. 1975; 59:219-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1155479

1373. Bennett WM, Aronoff GR, Morrison G et al. Drug prescribing in renal failure: dosing guidelines for adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 1983; 3:155-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6356890

1408. Lederle Laboratories. Methotrexate sodium tablets, methotrexate sodium and methotrexate LPF(R)sodium parenteral prescribing information. Pearl River, NY; 1996 Feb.

1414. Behrman RE, Vaughn VC III, eds. Nelson textbook of pediatrics. 12th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company: 1983:403-5,619-25,1823.

1423. Kaplan JM, McCracken GH, Horton LJ et al. Pharmacologic studies in neonates given large doses of ampicillin. J Pediatr. 1974; 84:571-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4600568

1568. Matsuda S. Transfer of antibiotics into maternal milk. Biol Res Pregnancy. 1984; 5:57-60.

1647. American Academy of Pediatrics. Report of the task force of diagnosis and management of meningitis. Pediatrics. 1986; 78(Suppl):959-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3763317

1903. Campoli-Richards DM, Brogden RN. Sulbactam/ampicillin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1987; 33:577-609. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3038500

1954. Itokazu GS, Danziger LH. Ampicillin-sulbactam and ticarcillin-clavulanic acid: a comparison of their in vitro activity and review of their clinical efficacy. Pharmacotherapy. 1991; 11:382-414. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1745624

1955. Noguchi JK, Gill MA. Sulbactam: a β-lactamase inhibitor. Clin Pharm. 1988; 7:37-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3278833

HID. Trissel LA. Handbook on injectable drugs. 17th ed. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2013:101-13.

Related/similar drugs

Frequently asked questions

More about ampicillin

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (5)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: aminopenicillins

- Breastfeeding