Rivaroxaban (Monograph)

Brand name: Xarelto

Drug class: Direct Factor Xa Inhibitors

Chemical name: 5-Chloro-N-[[(5S)-2-oxo-3-[4-(3-oxo-4-morpholinyl)phenyl]-5-oxazolidinyl]methyl]-2-thiophenecarboxamide

Molecular formula: C19H18ClN3O5S

CAS number: 366789-02-8

Warning

- Risk of Thrombosis Following Premature Discontinuance of Anticoagulation

-

Premature discontinuance of any oral anticoagulant, including rivaroxaban, increases risk of thrombotic events.1

If discontinuance is required for reasons other than pathologic bleeding or completion of a course of therapy, consider coverage with an alternative anticoagulant.1

- Spinal/Epidural Hematoma

-

Risk of epidural or spinal hematomas and neurologic injury, including long-term or permanent paralysis, in patients who are anticoagulated and also receiving neuraxial (spinal/epidural) anesthesia or spinal puncture.1

-

Risk increased by use of indwelling epidural catheters or by concomitant use of drugs affecting hemostasis (e.g., NSAIAs, platelet-aggregation inhibitors, other anticoagulants).1

-

Risk also increased by history of traumatic or repeated epidural or spinal puncture, spinal deformity, or spinal surgery.1

-

Optimal timing between administration of rivaroxaban and neuraxial procedures not known.1

-

Monitor frequently for signs and symptoms of neurologic impairment and treat urgently if neurologic compromise noted.1

-

Consider potential benefits versus risks of spinal or epidural anesthesia or spinal puncture in patients receiving or being considered for anticoagulant therapy.1

Introduction

Anticoagulant; an oral, direct, activated factor X (Xa) inhibitor.1 2 3 4 5 7 8 9 12 16 17 18 20 32 33

Uses for Rivaroxaban

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Reduction in the risk of stroke and systemic embolism in adults with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation.1 32 33 37

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs; apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, rivaroxaban) are noninferior or superior to warfarin in reducing thromboembolic risk in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (i.e., atrial fibrillation in the absence of moderate-to-severe mitral stenosis or a mechanical heart valve), and associated with reduced risk of serious bleeding.1 82 87

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), American Stroke Association (ASA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and other experts recommend antithrombotic therapy in all patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (i.e., atrial fibrillation in the absence of rheumatic mitral stenosis, a prosthetic heart valve, or mitral valve repair) who are considered to be at increased risk of stroke, unless contraindicated.80 81 82 989 990 999 1007 1017

Current guidelines recommend use of the CHA2DS2-VASc risk stratification tool to assess a patient’s risk of stroke and need for anticoagulant therapy.82 989 1007

Experts state that antithrombotic therapy generally is not necessary in low-risk patients (CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 in males or 1 in females), but should be considered or recommended in all higher-risk patients.87 989 1007 1017

In patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who are eligible for oral anticoagulant therapy, DOACs are recommended over warfarin based on improved safety and similar or improved efficacy.82 87 989 1007

Relative efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban and other DOACs (e.g., apixaban, dabigatran) have not been fully elucidated.37 40 49 50 68 989

When selecting an appropriate anticoagulant, consider factors such as the absolute and relative risks of stroke and bleeding; costs; patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities; and other clinical factors such as renal function and degree of international normalized ratio (INR) control (if the patient has been taking warfarin).80 81 82 83 84 989 1007

Experts state that antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial flutter generally should be managed in the same manner as in patients with atrial fibrillation.80 82 999 1007

DOACs including rivaroxaban have been used for pharmacologic cardioversion† [off-label] in patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter of >48 hours’ duration or of unknown duration; DOACs are recommended as an alternative to warfarin in this setting.87 1007

Use of rivaroxaban not recommended in patients with prosthetic heart valves.1 In patients with transcatheter aortic valve replacement, rivaroxaban was associated with higher rates of death and bleeding compared to antiplatelet therapy.1 Safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban not established in patients with other prosthetic heart valves or other valve procedures.1

Venous Thromboembolism – Treatment and Secondary Prevention

Initial treatment of DVT and/or PE in adults.1 59 60 1005 Also used for reduction in the risk of recurrent DVT and/or PE in adults at continued risk for recurrent DVT and/or PE after completion of initial treatment lasting at least 6 months.1 59

Treatment of VTE and reduction in the risk of recurrent VTE in pediatric patients (from birth to <18 years of age) after at least 5 days of initial parenteral anticoagulation therapy.1

Not recommended as initial therapy (as an alternative to unfractionated heparin) for treatment of PE in patients with hemodynamic instability or who may receive thrombolytic therapy or undergo pulmonary embolectomy.1

Recommended by ACCP, American Society of Hematology (ASH), and the Anticoagulation Forum as an acceptable option for initial and long-term anticoagulant therapy in patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg and/or PE.1005 1006 1008 1144

DOACs are among several anticoagulants that can be used for treatment of VTE.1144 DOACs have similar efficacy to warfarin, but reduced bleeding (particularly intracranial hemorrhage) and greater convenience for patients and healthcare providers.1144

DOACs generally should not be used in settings with high risk of bleeding (e.g., hemorrhagic lesion, renal/hepatic impairment, thrombocytopenia, GI or genitourinary malignancy, mucosal lesion, CNS malignancy or bleeding, recent surgery), or in patients with morbid obesity (body weight >120 kg or BMI ≥40 mg/m2), drug-drug interactions, or GI complications affecting oral therapy (e.g., poor absorption, nausea and vomiting) because of the lack of safety data.1102 1144

In patients with cancer and established VTE, low molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) or oral factor Xa inhibitors (e.g., apixaban, rivaroxaban, edoxaban) are generally recommended over warfarin for long-term anticoagulation.1102 1103 1144 ACCP and ASH recommend the use of an oral factor Xa inhibitor over LMWH for the initiation and treatment phases of therapy in patients with cancer-associated thrombosis.1103 1144

Thromboprophylaxis in Hip- or Knee-Replacement Surgery

Prevention of postoperative DVT, which may lead to PE, in adult patients undergoing hip- or knee-replacement surgery.1 2 3 4 5 6

More effective than enoxaparin in preventing DVT and associated PE in patients undergoing elective total hip- or knee-replacement surgery with similar bleeding rates.1 2 3 4 5 6 12 29 30 37

Routine thromboprophylaxis is recommended in all patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery, including total hip- or knee-replacement surgery, because of the high risk of postoperative VTE.1003

ACCP and other clinicians consider DOACs an acceptable option for pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing total hip- or knee-replacement surgery.12 29 37 1003

Drug selection and duration of therapy should be individualized based on type of surgery, patient risk factors for embolism and bleeding, costs, patient compliance, preference, tolerance, and comorbidities, and other clinical factors such as renal function.1003 1108

Thromboprophylaxis in Acutely Ill Medical Patients

Prevention of VTE and VTE-related death during hospitalization and after discharge in adults admitted for an acute medical illness who are at risk for thromboembolic complications due to moderate or severe restricted mobility and other risk factors for VTE and are not at high risk of bleeding.1

Do not use for primary VTE prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients with the following conditions due to increased risk of bleeding: history of bronchiectasis, pulmonary cavitation or pulmonary hemorrhage, active cancer (i.e., undergoing acute, in-hospital cancer treatment), active gastroduodenal ulcer in the 3 months prior to treatment, history of bleeding in the 3 months prior to treatment, or dual antiplatelet therapy.1

ASH issued a strong recommendation to use LMWHs instead of DOACs for VTE prophylaxis in acutely ill hospitalized medical patients, and also strongly recommends inpatient VTE prophylaxis with LMWH only rather than inpatient and extended-duration outpatient VTE prophylaxis with DOACs.1116

Thromboprophylaxis in Cancer Patients

American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline states that high-risk outpatients with cancer (Khorana score ≥2 prior to starting a new systemic chemotherapy regimen) may be offered thromboprophylaxis with rivaroxaban, apixaban, or a LMWH provided there are no significant risk factors for bleeding and no drug interactions.1102 1103

ASH guideline suggests thromboprophylaxis with a DOAC (rivaroxaban or apixaban) in ambulatory cancer patients at intermediate to high risk for thrombosis.1103

Consider patient's individual risk for thrombosis and risk of bleeding when deciding whether to administer thromboprophylaxis.1102 1103

Coronary Artery Disease

Used in conjunction with aspirin to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events (e.g., cardiovascular death, MI, stroke) in adults with coronary artery disease (CAD).1 200

Has been shown to reduce risk of thrombotic events when used in conjunction with low-dose aspirin, but associated with a higher risk of bleeding compared with aspirin alone.1 200 1119

May consider use in CAD patients after weighing patient’s risk of ischemic events against bleeding risk.1119 1121

Peripheral Artery Disease

Used in conjunction with aspirin to reduce the risk of major thrombotic vascular events (MI, ischemic stroke, acute limb ischemia, and major amputation of a vascular etiology) in adults with peripheral artery disease (PAD), including patients who have recently undergone a lower extremity revascularization procedure due to symptomatic PAD.1 200 1122 1123 1142

Congenital Heart Disease

Used for thromboprophylaxis following the Fontan procedure in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age with congenital heart disease.1 1135 1136

Rivaroxaban Dosage and Administration

General

Pretreatment Screening

-

Assess renal function in all patients prior to initiating rivaroxaban therapy.1

-

In adults, calculate creatinine clearance using actual body weight and the Cockcroft-Gault method.1

-

In children <1 year of age, determine renal function using serum creatinine (Scr) as follows based on the 97.5th percentile of creatinine: 0.52 mg/dL in children 2 weeks of age; 0.46 mg/dL in children 3 weeks of age; 0.42 mg/dL in children 4 weeks of age; 0.37 mg/dL in children 2 months of age; 0.34 mg/dL in children 3 to 9 months of age; 0.36 mg/dL in children 10 to 12 months of age. 1

-

In children ≥1 year of age, avoid use when eGFR <50 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.1 If Scr is measured by an enzymatic creatinine method that has been calibrated to be traceable to isotope dilution mass spectrometry (IDMS), eGFR can be calculated using the updated Schwartz formula as follows: eGFR (Schwartz) = (0.413 × height in cm)/Scr in mg/dL.1 If Scr is measured with routine methods not recalibrated to be traceable to IDMS, the eGFR should be obtained from the original Schwartz formula as follows: eGFR (mL/minute per 1.73 m2) = k × height in cm/Scr in mg/dL where k is the proportionality constant as follows (k=0.55 in children 1 to 13 years of age; k=0.55 in girls >13 and <18 years of age; k=0.70 in boys >13 and <18 years of age).1

Patient Monitoring

-

Periodically assess renal function as clinically indicated (i.e., more frequently in situations in which renal function may decline or improve, the elderly) and adjust therapy accordingly.1

-

When used in children for treatment of VTE or thromboprophylaxis after the Fontan procedure, monitor body weight as dosage is based on body weight.1

-

If rivaroxaban is administered in an epidural or spinal anesthesia/analgesia or lumbar puncture setting, frequently monitor for signs or symptoms of neurological impairment (e.g., numbness, tingling, weakness in lower limbs, bowel and/or bladder dysfunction).1

-

Monitor patients for any signs or symptoms of bleeding (e.g., unusual bruising) during therapy.1

-

Routine monitoring of coagulation status is not necessary during rivaroxaban therapy because of the drug's predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects.10 12 14 20 28 46 54 55 56 57 However, in certain situations, such as in the case of overdosage or in patients with hemorrhagic or thromboembolic complications, it may be useful to assess the degree of anticoagulation.7 28 55 It has been suggested that the prothrombin (PT) test may be used to assess rivaroxaban plasma concentrations since the drug prolongs PT in a concentration-dependent manner; however, PT test results may vary depending on the type of reagent and may not be a reliable indicator of the degree of anticoagulation with rivaroxaban.28 54 55 56 57 58 The international normalized ratio (INR) is calibrated specifically for vitamin K antagonists (e.g., warfarin) and should not be used to monitor the effects of rivaroxaban.28 54 58

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

Per the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), rivaroxaban is a high-alert medication that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error.1169

Oral Administration

Administer orally (as tablets or oral suspension).1

Administration in Pediatric Patients

In pediatric patients, 10, 15, or 20 mg tablets or the oral suspension may be administered.1 Splitting tablets or administration of the 2.5 mg tablets not recommended.1

In pediatric patients treated for VTE, administer all doses with feeding or food.1

In pediatric patients with congenital heart disease after the Fontan Procedure, administer rivaroxaban with or without food.1

Missed dose instructions in children are based on frequency of dosing.1 If administered once daily, take missed dose as soon as possible, but only on the same day.1 Skip the dose if this is not possible.1 If administered twice daily, take missed morning dose as soon as possible or take together with the evening dose.1 Take a missed evening dose as soon as possible, but only during that evening.1 If administered 3 times a day, skip missed dose and resume regular dosing schedule when next dose is due, without compensating for the missed dose.1 101

If the child vomits or spits up a dose within 30 minutes, administer a new dose.1 Beyond 30 minutes, do not repeat the dose and administer next dose at its scheduled time.1

Administration in Adults

In adult patients, administer 15- or 20-mg tablets with food; administer 2.5- or 10-mg tablets with or without food.1

Missed dose instructions in adults are based on dose and/or frequency of dosing.1 If a 2.5-mg dose of rivaroxaban is missed, take a single 2.5-mg dose as recommended at the next scheduled time.1 If a dose is missed in patients receiving a dosage of 10, 15, or 20 mg once daily, take the missed dose immediately.1 101 Do not double the dose within the same day to make up for a missed dose.1 101 If a dose is missed in patients receiving a dosage of 15 mg twice daily, take the dose immediately upon remembering; if necessary, take two 15-mg tablets at the same time to ensure full intake of the 30-mg daily dose.1 Resume the regular twice-daily dosing schedule the following day.1

In adults who are unable to swallow whole tablets, crush rivaroxaban tablets and mix with applesauce immediately before administration.1 When given orally as a crushed 15- or 20-mg tablet, immediately follow the dose of rivaroxaban with food.1 In patients requiring a nasogastric (NG) or gastric feeding tube (GT), administer rivaroxaban tablets by crushing and suspending the drug in 50 mL of water; enteral feeding via the tube should immediately follow administration of a 15- or 20-mg tablet.1

Preparation of Oral Suspension

Reconstitute granules for oral suspension at the time of dispensing to provide a suspension containing 1 mg rivaroxaban per 1 mL.1 Tap the bottle to loosen granules and add 150 mL purified water; shake for 60 seconds until suspension is uniform.1

May be administered via NG or GT; after administration, flush feeding tube with water.1

Immediately follow administration with an enteral feeding when the dose and/or indication (e.g., pediatric VTE treatment) requires administration with food.1

Dosage

Pediatric Patients

Treatment and Secondary Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism

Oral

Do not administer rivaroxaban until patient has completed at least 5 days of an initial parenteral anticoagulant (e.g., unfractionated heparin, LMWH).1

The recommended dosage and frequency of rivaroxaban for treatment of VTE and reduction in risk of recurrent VTE in pediatric patients (from birth to <18 years of age) is based on body weight (see Table 1).

|

Dosage form |

Body weight |

Dosage |

Total daily dose |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral suspension only |

2.6 to 2.9 kg |

0.8 mg 3 times a day |

2.4 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

3 to 3.9 kg |

0.9 mg 3 times a day |

2.7 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

4 to 4.9 kg |

1.4 mg 3 times a day |

4.2 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

5 to 6.9 kg |

1.6 mg 3 times a day |

4.8 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

7 to 7.9 kg |

1.8 mg 3 times a day |

5.4 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

8 to 8.9 kg |

2.4 mg 3 times a day |

7.2 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

9 to 9.9 kg |

2.8 mg 3 times a day |

8.4 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

10 to 11.9 kg |

3 mg 3 times a day |

9 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

12 to 29.9 kg |

5 mg twice daily |

10 mg |

|

Oral suspension OR tablets |

30 to 49.9 kg |

15 mg once daily |

15 mg |

|

Oral suspension OR tablets |

≥50 kg |

20 mg once daily |

20 mg |

Congenital Heart Disease

Oral

The recommended dosage and frequency of rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis following the Fontan procedure in pediatric patients ≥2 years of age with congenital heart disease is based on body weight (see Table 2).1

|

Dosage form |

Body weight |

Dosage |

Total daily dose |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral suspension only |

7 to 7.9 kg |

1.1 mg twice daily |

2.2 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

8 to 9.9 kg |

1.6 mg twice daily |

3.2 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

10 to 11.9 kg |

1.7 mg twice daily |

3.4 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

12 to 19.9 kg |

2 mg twice daily |

4 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

20 to 29.9 kg |

2.5 mg twice daily |

5 mg |

|

Oral suspension only |

30 to 49.9 kg |

7.5 mg once daily |

7.5 mg |

|

Oral suspension OR tablets |

≥50 kg |

10 mg once daily |

10 mg |

Adults

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Oral

Patients with normal renal function (Clcr >50 mL/minute): 20 mg once daily with the evening meal.1

Treatment and Secondary Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism

Oral

Initial treatment of acute DVT and/or PE: 15 mg twice daily for the first 21 days, followed by 20 mg once daily taken at approximately the same time every day with food.1 62 Initial twice-daily dosing may provide higher trough drug concentrations and improved thrombus regression.60 62 64 65

Continued prophylaxis (after initial 6 months of anticoagulant treatment) to reduce risk of recurrent DVT and/or PE (secondary prevention): 10 mg once daily.1

Determine optimum duration of anticoagulation based on individual clinical situation (e.g., location of thrombi, presence or absence of precipitating factors for thrombosis, presence of cancer, risk of bleeding).1005 In general, ACCP states that anticoagulant therapy should be continued beyond the acute treatment period for at least 3 months, and possibly longer in patients with a high risk of recurrence and low risk of bleeding.1005

Thromboprophylaxis in Hip- or Knee-Replacement Surgery

Oral

10 mg once daily.1

Administer first dose at least 6–10 hours after surgery, provided hemostasis has been established.1

Duration of therapy: Manufacturer recommends 35 days for patients undergoing hip-replacement surgery, 12 days for patients undergoing knee-replacement surgery.1

Thromboprophylaxis in Acutely Ill Medical Patients

Oral

10 mg once daily.1

Initiate in hospital and continue following discharge for a recommended duration of 31 to 39 days.1

Coronary Artery Disease

Oral

Risk reduction of major cardiovascular events: 2.5 mg twice daily, administered in conjunction with aspirin 75–100 mg once daily.1

Peripheral Artery Disease

Oral

Risk reduction of major cardiovascular events: 2.5 mg twice daily, administered in conjunction with aspirin 75–100 mg once daily.1

Transitioning from Other Anticoagulant Therapy

Transferring to Rivaroxaban from Warfarin

Discontinue warfarin and initiate rivaroxaban as soon as INR <3 in adults and <2.5 in pediatric patients.1

Transferring to Rivaroxaban from Other Anticoagulants

Administer initial dose of rivaroxaban within 2 hours of the next scheduled evening dose of the other anticoagulant (e.g., LMWH, non-warfarin oral anticoagulant) and discontinue other anticoagulant.1

When transferring to rivaroxaban from continuous IV heparin infusion, discontinue heparin infusion and initiate rivaroxaban at same time.1

Transitioning to Other Anticoagulant Therapy

Transferring from Rivaroxaban to Warfarin

Data not available to guide conversion from rivaroxaban to warfarin in adults.1 A suggested approach is to discontinue rivaroxaban and simultaneously initiate a parenteral anticoagulant and warfarin at the time of next scheduled dose of rivaroxaban.1 INR measurements may not be useful in determining appropriate dosage of warfarin during conversion.1

In pediatric patients, continue rivaroxaban for at least 2 days after the first dose of warfarin.1 After 2 days and prior to the next rivaroxaban dose, obtain an INR.1 Continue coadministration of rivaroxaban and warfarin until INR ≥2.1

Transferring from Rivaroxaban to Other Anticoagulants

When transferring from rivaroxaban to an anticoagulant (oral or parenteral) with a rapid onset of action, discontinue rivaroxaban and administer first dose of the other anticoagulant at the time of the next scheduled dose of rivaroxaban.1

Managing Anticoagulation in Patients Requiring Invasive Procedures

If temporary discontinuance of anticoagulation required prior to surgery or other invasive procedures, discontinue rivaroxaban ≥24 hours prior to procedure.1

In deciding whether a procedure should be delayed, weigh increased risk of bleeding against urgency of intervention.1

Resume therapy after procedure once adequate hemostasis established; if oral anticoagulation not possible, consider use of a parenteral anticoagulant.1

Special Populations

Dosage in Hepatic Impairment

Avoid use in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment or any hepatic disease associated with coagulopathy.1

Dosage in Renal Impairment

Embolism Associated with Atrial Fibrillation

Consider dosage adjustment or discontinuance of rivaroxaban in patients who develop acute renal failure.1

Patients with Clcr ≤50 mL/minute: Reduce dosage to 15 mg once daily with the evening meal.1

Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Pediatric Patients

Avoid use in patients ≥1 year of age with eGFR <50 mL/minute per 1.73 m2 and patients <1 year of age with Scr results above the 97.5th percentile.1

Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism in Adults

Avoid use in patients with Clcr <15 mL/minute.1 Close monitoring recommended in patients with Clcr 15–30 mL/minute.1

Discontinue in patients who develop acute renal failure.1

Thromboprophylaxis in Hip- or Knee-Replacement Surgery

Avoid use in patients with Clcr <15 mL/minute.1 Close monitoring recommended in patients with Clcr 15–30 mL/minute.1

Discontinue in patients who develop acute renal failure.1

Thromboprophylaxis in Acutely Ill Medical Patients

Avoid use in patients with Clcr <15 mL/minute.1 Close monitoring recommended in patients with Clcr 15–30 mL/minute.1

Discontinue in patients who develop acute renal failure.1

Coronary Artery Disease

Manufacturer states no dosage adjustment needed based on Clcr.1

Peripheral Artery Disease

Manufacturer states no dosage adjustment needed based on Clcr.1

Congenital Heart Disease

Avoid use in pediatric patients ≥1 year of age with eGFR <50 mL/minute per 1.73 m2 and in patients <1 year old with Scr results above the 97.5th percentile.1

Geriatric Patients

No specific dosage recommendations.1

Body Weight

Pediatric Patients: Monitor body weight; review the dose and frequency regularly to ensure an appropriate indication-based dose is maintained.1

Adults: Dosage adjustments not likely to be necessary in patients weighing ≤50 kg or >120 kg.1 9 21

Cautions for Rivaroxaban

Contraindications

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Risk of Thrombosis Following Premature Discontinuance of Anticoagulation

Premature discontinuance in the absence of adequate alternative anticoagulation may increase risk of thromboembolic events.1 (See Boxed Warning.) An increased risk of stroke was observed during transition from rivaroxaban to warfarin therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation.1 Such patients generally had been switched to warfarin without a period of concurrent warfarin and rivaroxaban therapy.1

If discontinuance of rivaroxaban required for reasons other than pathologic bleeding (e.g., prior to surgery or other invasive procedures) or completion of a course of therapy, consider coverage with an alternative anticoagulant.1 Ensure continuous anticoagulation during transition to alternative anticoagulant while minimizing risk of bleeding.83 Particular caution advised when switching from a factor Xa inhibitor to warfarin therapy because of warfarin's slow onset of action.83

Advise patients regarding importance of adhering to therapeutic regimen and on steps to take if doses are missed.1

Spinal/Epidural Hematoma

Epidural or spinal hematoma reported with concurrent use of anticoagulants and neuraxial (spinal/epidural) anesthesia or spinal puncture procedures.1 Such hematomas have resulted in neurologic injury, including long-term or permanent paralysis.1 (See Boxed Warning.)

To reduce risk of bleeding with concurrent use of rivaroxaban and neuraxial anesthesia or spinal puncture, carefully consider the pharmacokinetic profile of the anticoagulant in relation to the timing of such procedures.1

Do not remove indwelling epidural or intrathecal catheters before ≥2 half-lives have elapsed (i.e., 18 hours in patients 20–45 years of age; 26 hours in patients 60–76 years of age) after a dose of rivaroxaban, and administer next dose ≥6 hours after catheter removal; optimal timing between administration of rivaroxaban and neuraxial procedures to reach sufficiently low anticoagulant effect not known.1 If traumatic puncture occurs, delay rivaroxaban administration for 24 hours.1

Frequently monitor for signs of neurologic impairment (e.g., midline back pain; numbness, tingling, or weakness in lower limbs; bowel or bladder dysfunction).1 If spinal hematoma suspected, diagnose and treat immediately; consider spinal cord decompression even though such treatment may not prevent or reverse neurologic sequelae.1 Carefully consider potential benefits versus risks of neuraxial intervention in patients who are currently receiving or will receive anticoagulant prophylaxis.1

Other Warnings and Precautions

Bleeding

Rivaroxaban increases risk of hemorrhage and can cause serious, sometimes fatal bleeding.1 2 12 32 59 60 Weigh risk of bleeding against risk of thrombotic events in patients with increased risk of bleeding.1 Promptly evaluate any manifestations of blood loss during therapy.1 Discontinue if active pathologic hemorrhage occurs.1 However, should not readily discontinue anticoagulation for commonly occurring minor or “nuisance” bleeding.83

Renal impairment and concomitant use of drugs that affect hemostasis (e.g., aspirin or other NSAIAs, fibrinolytics, SNRIs, SSRIs, thienopyridines, other antithrombotic agents) or drugs that are combined P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and CYP3A4 inhibitors (e.g., ketoconazole, ritonavir) may increase risk of bleeding.1 5 6 8 30

Discontinue rivaroxaban and initiate appropriate treatment if bleeding associated with overdosage occurs.1 7 49 50 68 Not expected to be dialyzable because of high plasma protein binding.1

Factor Xa (recombinant), inactivated-zhzo (also known as andexanet alfa) is a specific reversal agent for the anticoagulant effects of rivaroxaban.90 91 92 Safety of factor Xa (recombinant), inactivated-zhzo not established in patients who have experienced a thromboembolic event or disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) within 2 weeks prior to the life-threatening bleeding event requiring treatment with the drug or in those who have received prothrombin complex concentrates (PCC), recombinant factor VIIa, or whole blood products ≤7 days prior to the bleeding event.90

May consider use of procoagulant reversal agents such as 4-factor PCC when factor Xa (recombinant), inactivated-zhzo is not available.1 43 68

Protamine sulfate and vitamin K not expected to affect anticoagulant activity of rivaroxaban, and no experience with antifibrinolytic agents (tranexamic acid, aminocaproic acid) or systemic hemostatics (desmopressin).1

Patients with Prosthetic Heart Valves

Efficacy and safety not established; use generally not recommended.1 The manufacturer states that rivaroxaban is not recommended in transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) patients.1

Patients with Pulmonary Embolism

Not recommended as initial therapy (as alternative to unfractionated heparin) in patients with PE who have hemodynamic instability or who may receive thrombolytic therapy or undergo pulmonary embolectomy.1

Thrombosis Risk in Triple Positive Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Risk of recurrent thrombotic events in patients with triple-positive antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) (i.e., positive for lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and anti-beta 2-glycoprotein I antibodies); use not recommended in these patients.1

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

No adequate data in pregnant women; pronounced maternal bleeding, post-implantation pregnancy loss, and fetotoxic effects observed in animals.1

Use with caution in pregnant women and only when potential benefits justify potential risks (e.g., hemorrhage, emergent delivery while receiving an anticoagulant that is not readily reversible).1 Closely monitor for bleeding manifestations (e.g., decline in hemoglobin and/or hematocrit, hypotension, fetal distress).1

ACCP recommends avoidance of rivaroxaban in pregnant women.1012 Women of childbearing potential should discuss pregnancy planning with their clinician prior to initiating therapy.1

Lactation

Distributed into human milk.1 Effects of rivaroxaban on the breastfed infant or on milk production unknown.1

Consider benefits of breast-feeding and clinical need for rivaroxaban in the woman along with any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed infant from the drug or underlying maternal condition.1

ACCP recommends alternative anticoagulants to rivaroxaban in nursing women.1012

Females and Males of Reproductive Potential

Assess for increased risk of bleeding potentially requiring surgical intervention in females of reproductive potential and those with abnormal uterine bleeding.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy for VTE treatment and secondary prevention established in children from birth to <18 years of age established.1 However not studied in children <6 months who were <37 weeks of gestation at birth, had <10 days of oral feeding, or had a body weight of <2.6 kg; not recommended in such patients because dosing cannot be reliably determined.1

Safety and efficacy for thromboprophylaxis following the Fontan procedure in children ≥2 years old with congenital heart disease established.1

The 10 mg, 15 mg, and 20 mg rivaroxaban tablets may be used in children; clinical studies have evaluated safety, efficacy, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic data in this patient population.1 No data with 2.5 mg tablets in children; therefore, not recommended.1

Consider the same warnings and precautions in children as recommended for adults.1

Geriatric Use

No substantial differences in efficacy relative to younger adults in clinical studies.1 Although older patients experienced a higher rate of thrombotic and bleeding events, risk-to-benefit profile was favorable in all age groups.1

Hepatic Impairment

Possible increased systemic exposure and pharmacodynamic effects (inhibition of factor Xa activity, PT prolongation) in patients with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B); clinically important effects in patients with mild hepatic impairment not observed.1 9 Pharmacokinetic profile not established in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C).1 9

Avoid use in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment or with any hepatic disease associated with coagulopathy.1

No clinical data are available in pediatric patients with hepatic impairment.1

Renal Impairment

Possible increased exposure and increased pharmacodynamic effects with decreasing renal function.1 9 12 18 27 Discontinue drug if acute renal failure develops.1

Patients receiving thromboprophylaxis for orthopedic surgery: Closely monitor those with moderate renal impairment (Clcr <15 to 30 mL/minute) and promptly evaluate if any manifestations of bleeding occur.1 Do not use in patients with Clcr <15 mL/minute.1 Close monitoring recommended for Clcr 15–30 mL/minute.1

Patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: Assess renal function periodically and adjust dosage accordingly.1 More frequent monitoring may be necessary in clinical situations in which renal function may decline.1

Patients with VTE: Do not use in patients with Clcr <30 mL/minute.1

Patients with CAD or PAD: Rivaroxaban dosage of 2.5 mg twice daily in patients with Clcr ≤30 mL/minute expected to result in rivaroxaban exposure similar to that observed in patients with moderate renal impairment, whose efficacy and safety outcomes were similar to those with preserved renal function.1

In patients with renal impairment, concomitant use of drugs that are combined P-gp and weak/moderate CYP3A4 inhibitors may substantially increase rivaroxaban exposure, which may increase risk of bleeding.1 Avoid use in patients with Clcr 15 to <80 mL/minute who are receiving a combined P-gp and moderate CYP3A inhibitor (e.g., erythromycin) concomitantly unless potential benefit justifies potential risk.1

Limited clinical data in pediatric patients ≥1 year of age with moderate or severe renal impairment (eGFR <50 mL/minute per 1.73 m2); avoid use.1

No clinical data in pediatric patients <1 year of age with Scr results above the 97.5th percentile; avoid use.1

Common Adverse Effects

Adults (>5%): Bleeding.1

Children (>10%): Bleeding, cough, vomiting, gastroenteritis.1

Drug Interactions

Metabolized by CYP 3A4/5 and 2J2.1 Does not inhibit CYP1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2J2, and 3A4 nor induce CYP1A2, 2B6, 2C19, and 3A4 in vitro; pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely with drugs metabolized by these enzymes.1 8 9

Substrate of the efflux transporters P-gp and ABCG2 (breast cancer resistance protein [BCRP]); does not appear to inhibit these transporters.1

Drugs Affecting Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Inhibitors of CYP3A4/5 or 2J2: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (increased rivaroxaban exposure).1

Inducers of CYP3A4/5 or 2J2: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (decreased rivaroxaban exposure).1

Drugs Affecting Efflux Transport Systems

Inhibitors of P-gp or ABCG2: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (increased rivaroxaban exposure).1

Inducers of P-gp or ABCG2: Potential pharmacokinetic interaction (decreased rivaroxaban exposure).1

Drugs Affecting Both P-gp and CYP3A4

Combined P-gp and CYP3A4 inhibitors: Possible increased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may increase risk of bleeding.1 Extent of interaction appears to be related to degree of P-gp or CYP3A4 inhibition.1 No special precautions necessary when clinical data suggest that increased exposure is unlikely to affect bleeding.1 Avoid concomitant use of combined P-gp and potent CYP3A4 inhibitors.1

Combined P-gp and potent CYP3A4 inducers: Possible decreased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may decrease efficacy.1 Avoid concomitant use.1

Results of pharmacokinetic trial suggest that exposure to rivaroxaban may be substantially increased in patients with renal impairment receiving full-dose (20 mg) rivaroxaban in conjunction with a combined P-gp inhibitor and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor.1 Increased bleeding risk not observed in a clinical study in patients with renal impairment (Clcr 30–49 mL/minute) who received such a combination.1 However, manufacturer advises against concomitant use of rivaroxaban and a combined P-gp and moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor in patients with Clcr 15–80 mL/minute unless potential benefits justify potential risks.1

Drugs Affecting Hemostasis

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage.1 8 Promptly evaluate any manifestations of bleeding.1

Protein-bound Drugs

Potential interaction with other highly protein-bound drugs.8

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Antacids (aluminum- or magnesium-containing) |

No effect on rivaroxaban bioavailability or systemic exposure1 |

|

|

Antiarrhythmic agents, class III (amiodarone, dronedarone) |

Amiodarone: No increased risk of bleeding observed in patients with Clcr 30–49 mL/minute Dronedarone: Substantial increases in rivaroxaban exposure may occur in patients with renal impairment1 203 |

|

|

Anticoagulants, other |

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage1 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Antidepressants (SNRIs, SSRIs) |

May impair hemostasis and may further increase bleeding risk1 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Antifungals, azole (fluconazole, itraconazole, ketoconazole) |

Fluconazole: Possible increased AUC and peak plasma concentrations of rivaroxaban1 Itraconazole, ketoconazole: Possible increased rivaroxaban exposure, which may increase risk of bleeding1 202 203 |

Itraconazole, ketoconazole: Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Antiretrovirals, HIV protease inhibitors |

Lopinavir/ritonavir, indinavir, ritonavir: Possible increased rivaroxaban exposure, which may increase risk of bleeding1 202 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Aspirin |

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage1 5 6 8 30 Increased bleeding time, but no effect on aspirin's inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation; no substantial change in pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban1 8 9 23 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Atorvastatin |

||

|

Calcium-channel blocking agents (diltiazem, verapamil) |

Concomitant use of verapamil or diltiazem not associated with increased risk of stroke or non-CNS embolism; increased risk of major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage observed in ROCKET AF204 In a case-cohort analysis, coadministration of rivaroxaban with diltiazem did not result in an increased rate of bleeding205 |

|

|

Carbamazepine |

Possible decreased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may decrease efficacy1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Clopidogrel |

Increased bleeding time; no change in pharmacokinetics of either drug1 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Conivaptan |

Possible increased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may increase risk of bleeding1 203 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Digoxin |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 |

|

|

Enoxaparin |

Additive effects on anti-factor Xa activity; pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban not affected1 9 39 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 Avoid concomitant use unless benefit outweighs risk1 |

|

Macrolides (clarithromycin, erythromycin) |

Clarithromycin, erythromycin: Increased rivaroxaban exposure; however, not expected to increase risk of bleeding1 Erythromycin: Substantial increases in rivaroxaban exposure may occur in patients with renal impairment1 |

No special precautions necessary in patients with normal renal function1 Erythromycin: Do not use concomitantly in patients with moderate renal impairment unless potential benefits justify potential risks1 |

|

Midazolam |

Pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 |

|

|

NSAIAs (e.g., naproxen) |

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage1 5 6 8 30 Naproxen: Bleeding time increased slightly, but no substantial pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interaction1 8 9 24 39 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Omeprazole |

||

|

Phenytoin |

Possible decreased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may decrease efficacy1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Platelet-aggregation inhibitors |

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage1 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 |

|

Ranitidine |

No effect on rivaroxaban bioavailability or systemic exposure1 |

|

|

Rifampin |

Decreased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects; possible decreased efficacy1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) |

Possible decreased rivaroxaban exposure and pharmacodynamic effects, which may decrease efficacy1 |

Avoid concomitant use1 |

|

Thrombolytic agents |

Potential increased risk of hemorrhage1 |

|

|

Warfarin |

Additive effects on factor Xa inhibition and PT prolongation; pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban not affected1 |

Promptly evaluate if bleeding manifestations occur1 Avoid concomitant use unless benefit outweighs risk1 |

Rivaroxaban Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly and well absorbed following oral administration; bioavailability approximately 80–100% (2.5- and 10-mg doses) and 66% (20-mg dose).1 8 9 12 15 16 20

Following oral administration, peak plasma concentrations occur within 2–4 hours.1 8 9 12 15 16 46

Absorption dependent on site of release in the GI tract; exposure reduced when drug released into the proximal small intestine and further reduced when released in distal small intestine or ascending colon.1 (See Administration under Dosage and Administration.)

Not adsorbed to PVC or silicone nasogastric tubing when drug administered as suspension in water.1 (See Administration under Dosage and Administration.)

Food

Food increases peak plasma concentrations and systemic exposure to 20-mg dose; effects of food on 2.5- or 10-mg dose not expected to be clinically important.1 22 39

When administered as crushed tablets (20 mg) in applesauce, mean AUC and peak plasma concentrations comparable to those with whole tablets.1 When administered as crushed tablets in water via nasogastric tube followed by liquid meal, mean AUC with crushed tablets was comparable to that with a whole tablet, but mean peak plasma concentration was 18% lower.1

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into human milk.1

Crosses the placenta in animals.1

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 92–95% (mainly to albumin).1 9

Elimination

Metabolism

Undergoes oxidative degradation (by CYP3A4/5 and 2J) and hydrolysis.1 26 No major circulating metabolites identified.1 8 26

Elimination Route

Approximately 66% of administered dose eliminated renally (36% unchanged drug) and 28% eliminated in feces (7% unchanged drug).1 8 26

No substantial accumulation with multiple dosing.8 9

Not expected to be removed by dialysis due to high plasma protein binding.1

Half-life

5–9 hours in healthy individuals 20–45 years of age.1 8

Special Populations

Exposure to rivaroxaban increased by 44, 52, or 64% in patients with mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment, respectively, compared with those with normal renal function.1 9 27

Substantial increased exposure in patients with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B).1 9

Systemic exposure in geriatric patients increased by approximately 50% compared with younger individuals, likely due to reduced total body and renal clearance; half-life 11–13 hours.1 9 12

The correlation between anti-factor Xa and plasma concentrations is linear with a slope close to 1 in children.1 The rate and extent of absorption were similar between the tablet and oral suspension; maximum serum concentration was observed at a median time of 1.5 to 2.2 hours.1 Mean half-life increased with increasing age.1 Plasma protein binding (in vitro) is approximately 90% in children 6 months to 9 years of age.1

Exposure to rivaroxaban on average 20–40% higher in patients of Japanese ancestry compared with other ethnicities (including Chinese); however, difference reduced after adjustment for body weight.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablet

25°C (excursions permitted to 15–30°C).1

Crushed tablets in water or applesauce: Stable for ≤4 hours.1

Oral Suspension

Unreconstituted granules and reconstituted suspension: 20–25°C (excursions permitted to 15–30°C).1

Use reconstituted oral suspension within 60 days.1

Actions

-

Selectively blocks active site of factor Xa; inhibits both free and prothrombinase-bound factor Xa.1 8 9 10 12 17

-

Inhibition of coagulation factor Xa prevents conversion of prothrombin to thrombin and subsequent thrombus formation.1 7 8 9 12 15 16 17 23

-

Unlike fondaparinux, unfractionated heparin, and LMWHs, rivaroxaban blocks factor Xa directly and does not require a cofactor (antithrombin III) to exert its anticoagulant activity.1 8 9 15 23

-

Inhibits factor Xa activity, PT, aPTT, and HepTest (an indirect measure of factor Xa activity) in a dose-dependent manner.1 8 12 15 18 20 43

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients to take rivaroxaban exactly as prescribed and to not discontinue therapy without first consulting a clinician.1

-

Advise patients to not split tablets to provide a fraction of a tablet dose.1

-

Advise patients to use the provided oral syringes when administering the reconstituted oral suspension.1

-

Advise patients regarding whether the dose needs to be taken with or without food.1

-

Inform patients who cannot swallow tablets whole to crush the tablets and combine with a small amount of applesauce followed by food.1 The oral suspension may be used for children unable to swallow whole tablets or for doses not available as a tablet.1

-

Advise patients with a nasogastric or gastric tube to crush rivaroxaban tablets, mix with a small amount of water, and administer immediately via the tube.1

-

Advise patients to administer a new dose if a child vomits or spits up the dose within 30 minutes after receiving the dose.1 However, if the child vomits more than 30 minutes after the dose is taken, do not re-administer the dose and take the next dose as scheduled.1 If a child vomits or spits up the dose repeatedly, contact the child’s doctor right away.1

-

Advise patients of the importance of having an adult caregiver administer the dose to pediatric patients.1

-

Advise patients that if a dose is missed, management is based upon the indication for use, dose, and dosage frequency.1

-

Inform patients that they may bruise and/or bleed more easily and that a longer than normal time may be required to stop bleeding when taking rivaroxaban.1 Advise patients to inform clinicians about any unusual bleeding or bruising during therapy.1

-

Advise patients undergoing neuraxial anesthesia or spinal puncture procedures to monitor for manifestations of spinal or epidural hematoma (e.g., tingling or numbness in lower limbs, muscle weakness, back pain, stool or urine incontinence); immediately contact a clinician if any of these symptoms occur.1

-

Advise patients to inform clinicians that they are receiving rivaroxaban therapy before scheduling any medical, surgical, or invasive procedure, including dental procedures.1

-

Advise females to inform their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary and herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illnesses.1

-

Advise patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

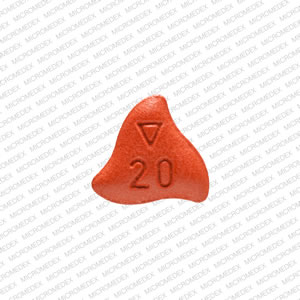

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

For Suspension |

1 mg/1 mL after reconstitution |

Xarelto |

Janssen |

|

Tablets |

2.5 mg |

Xarelto |

Janssen |

|

|

10 mg |

Xarelto |

Janssen |

||

|

15 mg |

Xarelto |

Janssen |

||

|

20 mg |

Xarelto |

Janssen |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions March 23, 2023. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Janssen. Xarelto (rivaroxaban) oral tablets prescribing information. Titusville, NJ: 2021 Dec.

2. Eriksson BI, Borris LC, Friedman RJ et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after hip arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:2765-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18579811?dopt=AbstractPlus

3. Kakkar AK, Brenner B, Dahl OE et al. Extended duration rivaroxaban versus short-term enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip arthroplasty: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2008; 372:31-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18582928?dopt=AbstractPlus

4. Lassen MR, Ageno W, Borris LC et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358:2776-86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18579812?dopt=AbstractPlus

5. Turpie AG, Lassen MR, Davidson BL et al. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for thromboprophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty (RECORD4): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2009; 373:1673-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19411100?dopt=AbstractPlus

6. Turpie AG, Lassen MR, Eriksson BI et al. Rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after hip or knee arthroplasty. Pooled analysis of four studies. Thromb Haemost. 2011; 105:444-53. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21136019?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. Van Thiel D, Kalodiki E, Wahi R et al. Interpretation of benefit-risk of enoxaparin as comparator in the RECORD program: rivaroxaban oral tablets (10 milligrams) for use in prophylaxis in deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients undergoing hip or knee replacement surgery. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009 Jul-Aug; 15:389-94.

8. Abrams PJ, Emerson CR. Rivaroxaban: a novel, oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Pharmacotherapy. 2009; 29:167-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19170587?dopt=AbstractPlus

9. Gulseth MP, Michaud J, Nutescu EA. Rivaroxaban: an oral direct inhibitor of factor Xa. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008; 65:1520-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18693206?dopt=AbstractPlus

10. Borris LC. Rivaroxaban, a new, oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor for thromboprophylaxis after major joint arthroplasty. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009; 10:1083-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19351271?dopt=AbstractPlus

12. Duggan ST, Scott LJ, Plosker GL. Rivaroxaban: a review of its use for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee replacement surgery. Drugs. 2009; 69:1829-51. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19719335?dopt=AbstractPlus

14. Fisher WD, Eriksson BI, Bauer KA et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis after orthopaedic surgery: pooled analysis of two studies. Thromb Haemost. 2007; 97:931-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17549294?dopt=AbstractPlus

15. Kubitza D, Becka M, Roth A et al. Dose-escalation study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban in healthy elderly subjects. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008; 24:2757-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18715524?dopt=AbstractPlus

16. Jiang J, Hu Y, Zhang J et al. Safety, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of single doses of rivaroxaban - an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor - in elderly Chinese subjects. Thromb Haemost. 2010; 103:234-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20062915?dopt=AbstractPlus

17. Graff J, von Hentig N, Misselwitz F et al. Effects of the oral, direct factor xa inhibitor rivaroxaban on platelet-induced thrombin generation and prothrombinase activity. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007; 47:1398-407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17873238?dopt=AbstractPlus

18. Mueck W, Borris LC, Dahl OE et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of once- and twice-daily rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing total hip replacement. Thromb Haemost. 2008; 100:453-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18766262?dopt=AbstractPlus

20. Mueck W, Becka M, Kubitza D et al. Population model of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor xa inhibitor--in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007; 45:335-44. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17595891?dopt=AbstractPlus

21. Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M et al. Body weight has limited influence on the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, or pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939) in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007; 47:218-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17244773?dopt=AbstractPlus

22. Kubitza D, Becka M, Zuehlsdorf M et al. Effect of food, an antacid, and the H2 antagonist ranitidine on the absorption of BAY 59-7939 (rivaroxaban), an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006; 46:549-58. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16638738?dopt=AbstractPlus

23. Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor--are not affected by aspirin. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006; 46:981-90. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16920892?dopt=AbstractPlus

24. Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W et al. Rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939)--an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor--has no clinically relevant interaction with naproxen. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007; 63:469-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17100983?dopt=AbstractPlus

25. Kubitza D, Mueck W, Becka M. Randomized, double-blind, crossover study to investigate the effect of rivaroxaban on QT-interval prolongation. Drug Saf. 2008; 31:67-77. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18095747?dopt=AbstractPlus

26. Weinz C, Schwarz T, Kubitza D et al. Metabolism and excretion of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor, in rats, dogs, and humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009; 37:1056-64. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19196845?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Kubitza D, Becka M, Mueck W et al. Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and safety of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010; 70:703-12. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2997310&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21039764?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. Lindhoff-Last E, Samama MM, Ortel TL et al. Assays for measuring rivaroxaban: their suitability and limitations. Ther Drug Monit. 2010; 32:673-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20844464?dopt=AbstractPlus

29. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, National Health Service. Rivaroxaban for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after total hip or total knee replacement in adults. London, UK. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009 Apr. Technology Appraisal Guidance, no 170.

30. Food and Drug Administration. FDA briefing document from the cardiovascular and renal drugs advisory committee meeting, March 19, 2009. From FDA website. http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/09/briefing/2009-4418b1-01-FDA.pdf

31. Sanofi-Aventis. Lovenox (enoxaparin sodium) injection prescribing information. Bridgewater, NJ: 2020 May.

32. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:883-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21830957?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. ROCKET AF Study Investigators. Rivaroxaban-once daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and Embolism Trial in Atrial Fibrillation: rationale and design of the ROCKET AF study. Am Heart J. 2010; 159:340-347.e1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20211293?dopt=AbstractPlus

36. Zuily S, Cohen H, Isenberg D et al. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome: Guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020; 18:2126-2137. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32881337?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Steffel J, Braunwald E. Novel oral anticoagulants: focus on stroke prevention and treatment of venous thrombo-embolism. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:1968-76, 1976a. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21421599?dopt=AbstractPlus

39. Walenga JM, Adiguzel C. Drug and dietary interactions of the new and emerging oral anticoagulants. Int J Clin Pract. 2010; 64:956-67. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20584229?dopt=AbstractPlus

40. Fleming TR, Emerson SS. Evaluating rivaroxaban for nonvalvular atrial fibrillation—regulatory considerations. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:1557-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21992495?dopt=AbstractPlus

41. Fox KA, Piccini JP, Wojdyla D et al. Prevention of stroke and systemic embolism with rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and moderate renal impairment. Eur Heart J. 2011; 32:2387-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21873708?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Jaeger M, Jeanneret B, Schaeren S. Spontaneous spinal epidural haematoma during Factor Xa inhibitor treatment (Rivaroxaban). Eur Spine J. 2011; :. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3369027&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21874549?dopt=AbstractPlus

43. Cuker A, Burnett A, Triller D et al. Reversal of direct oral anticoagulants: Guidance from the Anticoagulation Forum. Am J Hematol. 2019; 94:697-709. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30916798?dopt=AbstractPlus

44. Moore KT, Plotnikov AN, Thyssen A et al. Effect of Multiple Doses of Omeprazole on the Pharmacokinetics, Pharmacodynamics, and Safety of a Single Dose of Rivaroxaban. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2011; :. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21822144?dopt=AbstractPlus

46. Mueck W, Lensing AW, Agnelli G et al. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011; 50:675-86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21895039?dopt=AbstractPlus

47. Gnoth MJ, Buetehorn U, Muenster U et al. In vitro and in vivo P-glycoprotein transport characteristics of rivaroxaban. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011; 338:372-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21515813?dopt=AbstractPlus

49. Mega JL. A new era for anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:1052-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21870977?dopt=AbstractPlus

50. del Zoppo GJ, Eliasziw M. New options in anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365:952-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21830960?dopt=AbstractPlus

51. Bauer KA, Eriksson BI, Lassen MR et al. Fondaparinux compared with enoxaparin for the prevention of venous thromboembolism after elective major knee surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001; 345:1305-10. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11794149?dopt=AbstractPlus

54. Mueck W, Eriksson BI, Bauer KA et al. Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor--in patients undergoing major orthopaedic surgery. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008; 47:203-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18307374?dopt=AbstractPlus

55. Samama MM, Martinoli JL, LeFlem L et al. Assessment of laboratory assays to measure rivaroxaban--an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 2010; 103:815-25. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20135059?dopt=AbstractPlus

56. Kubitza D, Becka M, Wensing G et al. Safety, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacokinetics of BAY 59-7939--an oral, direct Factor Xa inhibitor--after multiple dosing in healthy male subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2005; 61:873-80. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16328318?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Hillarp A, Baghaei F, Fagerberg Blixter I et al. Effects of the oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban on commonly used coagulation assays. J Thromb Haemost. 2011; 9:133-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20946166?dopt=AbstractPlus

58. Samama MM, Guinet C. Laboratory assessment of new anticoagulants. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011; 49:761-72. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21288169?dopt=AbstractPlus

59. EINSTEIN Investigators, Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:2499-510. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21128814?dopt=AbstractPlus

60. EINSTEIN–PE Investigators, Büller HR, Prins MH et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:1287-97. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22449293?dopt=AbstractPlus

61. Cohen AT, Dobromirski M. The use of rivaroxaban for short- and long-term treatment of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2012; 107:1035-43. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22371186?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Buller HR, Lensing AW, Prins MH et al. A dose-ranging study evaluating once-daily oral administration of the factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban in the treatment of patients with acute symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: the Einstein-DVT Dose-Ranging Study. Blood. 2008; 112:2242-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18621928?dopt=AbstractPlus

63. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, National Health Service. Rivaroxaban for the treatment of deep vein thrombosis and prevention of recurrent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. London, UK. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2012 July. Technology Appraisal Guidance, no 261.

64. Agnelli G, Gallus A, Goldhaber SZ et al. Treatment of proximal deep-vein thrombosis with the oral direct factor Xa inhibitor rivaroxaban (BAY 59-7939): the ODIXa-DVT (Oral Direct Factor Xa Inhibitor BAY 59-7939 in Patients With Acute Symptomatic Deep-Vein Thrombosis) study. Circulation. 2007; 116:180-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17576867?dopt=AbstractPlus

65. Mueck W, Lensing AW, Agnelli G et al. Rivaroxaban: population pharmacokinetic analyses in patients treated for acute deep-vein thrombosis and exposure simulations in patients with atrial fibrillation treated for stroke prevention. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011; 50:675-86. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21895039?dopt=AbstractPlus

68. Miesbach W, Seifried E. New direct oral anticoagulants--current therapeutic options and treatment recommendations for bleeding complications. Thromb Haemost. 2012; 108:625-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22782297?dopt=AbstractPlus

80. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014; 64:e1-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24685669?dopt=AbstractPlus

81. Meschia JF, Bushnell C, Boden-Albala B et al. Guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:3754-832. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=5020564&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25355838?dopt=AbstractPlus

82. Kleindorfer DO, Towfighi A, Chaturvedi S et al. 2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2021; 52:e364-e467. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34024117?dopt=AbstractPlus

83. Heidbuchel H, Verhamme P, Alings M et al. EHRA practical guide on the use of new oral anticoagulants in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2013; 34:2094-106. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23625209?dopt=AbstractPlus

84. Senoo K, Lip GY. Comparative efficacy and safety of the non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants for patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015; 41:146-53. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25682085?dopt=AbstractPlus

85. Skjøth F, Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH et al. Efficacy and safety of edoxaban in comparison with dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. An indirect comparison analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2014; 111:981-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24577485?dopt=AbstractPlus

87. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society in Collaboration With the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2019; 140:e125-e151. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30686041?dopt=AbstractPlus

88. Sebaaly J, Kelley D. Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Obesity: An Updated Literature Review. Ann Pharmacother. 2020; 54:1144-1158. [PubMed]

89. Kido K, Lee JC, Hellwig T et al. Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Morbidly Obese Patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2020; 40:72-83.

90. Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Andexxa (iandexanet alfa injection) prescribing information. South San Francisco, CA; 2021 Feb.

91. Siegal DM, Curnutte JT, Connolly SJ et al. Andexanet alfa for the reversal of factor Xa inhibitor activity. N Engl J Med. 2015; 373:2413-24. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26559317?dopt=AbstractPlus

92. Connolly SJ, Milling TJ, Eikelboom JW et al. Andexanet alfa for acute major bleeding associated with factor Xa inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2016; 375:1131-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27573206?dopt=AbstractPlus

101. Janssen. Xarelto (rivaroxaban) oral tablets medication guide. Titusville, NJ: 2021 Dec.

200. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J et al. Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377:1319-1330. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28844192?dopt=AbstractPlus

201. Weitz JI, Lensing AWA, Prins MH et al. Rivaroxaban or Aspirin for Extended Treatment of Venous Thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:1211-1222. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28316279?dopt=AbstractPlus

202. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Clinical pharmacology and biopharmaceutics reviews(s): application number 022406Orig1s000. From FDA website. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2011/022406Orig1s000ClinPharmR.pdf

203. Food and Drug Administration. Drug development and drug interactions: table of substrates, inhibitors, and inducers. From FDA website. Accessed 2019 Feb 25. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/developmentapprovalprocess/developmentresources/druginteractionslabeling/ucm093664.htm

204. Washam JB, Hellkamp AS, Lokhnygina Y et al. Efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban versus warfarin in patients taking nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers for atrial fibrillation (from the ROCKET AF Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2017; 120:588-594. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28645473?dopt=AbstractPlus

205. Bartlett JW, Renner E, Mouland E et al. Clinical safety outcomes in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation on rivaroxaban and diltiazem. Ann Pharmacother. 2019; 53:21-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30099888?dopt=AbstractPlus

989. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Develop with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021; 42:373-498. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32860505?dopt=AbstractPlus

990. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke. 2011; 42:227-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20966421?dopt=AbstractPlus

999. Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2011; 123:e269-367.

1003. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012; 141(2 Suppl):e278S-325S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3278063&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315265?dopt=AbstractPlus

1005. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, Blaivas A, Jimenez D, Bounameaux H, Huisman M, King CS, Morris TA, Sood N, Stevens SM, Vintch JRE, Wells P, Woller SC, Moores L. Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2016 Feb;149(2):315-352. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. Epub 2016 Jan 7. Erratum in: Chest. 2016 Oct;150(4):988. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26867832?dopt=AbstractPlus

1006. Ortel TL, Neumann I, Ageno W, Beyth R, Clark NP, Cuker A, Hutten BA, Jaff MR, Manja V, Schulman S, Thurston C, Vedantham S, Verhamme P, Witt DM, D Florez I, Izcovich A, Nieuwlaat R, Ross S, J Schünemann H, Wiercioch W, Zhang Y, Zhang Y. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv. 2020 Oct 13;4(19):4693-4738. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC7556153&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33007077?dopt=AbstractPlus

1007. Lip GYH, Banerjee A, Boriani G et al. Antithrombotic Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018; 154:1121-1201. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30144419?dopt=AbstractPlus

1008. Burnett AE, Mahan CE, Vazquez SR, Oertel LB, Garcia DA, Ansell J. Guidance for the practical management of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) in VTE treatment. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016 Jan;41(1):206-32. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1310-7. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC4715848&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26780747?dopt=AbstractPlus

1012. Bates SM, Greer IA, Middeldorp S et al. VTE, thrombophilia, antithrombotic therapy, and pregnancy: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012; 141(2 Suppl):e691S-736S. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3278054&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22315276?dopt=AbstractPlus

1017. Bushnell C, McCullough LD, Awad IA et al; on behalf of the American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, and Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in women: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45:1545-88. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24503673?dopt=AbstractPlus

1102. Key NS, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM et al. Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis and Treatment in Patients With Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020; 38:496-520. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31381464?dopt=AbstractPlus

1103. Lyman GH, Carrier M, Ay C, Di Nisio M, Hicks LK, Khorana AA, Leavitt AD, Lee AYY, Macbeth F, Morgan RL, Noble S, Sexton EA, Stenehjem D, Wiercioch W, Kahale LA, Alonso-Coello P. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention and treatment in patients with cancer. Blood Adv. 2021 Feb 23;5(4):927-974. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003442. Erratum in: Blood Adv. 2021 Apr 13;5(7):1953. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC7903232&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/33570602?dopt=AbstractPlus

1105. Mulder FI, Bosch FTM, Young AM et al. Direct oral anticoagulants for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood. 2020; 136:1433-1441. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32396939?dopt=AbstractPlus

1106. Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J et al. Comparison of an Oral Factor Xa Inhibitor With Low Molecular Weight Heparin in Patients With Cancer With Venous Thromboembolism: Results of a Randomized Trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol. 2018; 36:2017-2023. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29746227?dopt=AbstractPlus

1107. Cohen AT, Hamilton M, Mitchell SA et al. Comparison of the Novel Oral Anticoagulants Apixaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban, and Rivaroxaban in the Initial and Long-Term Treatment and Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015; 10:e0144856. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC4696796&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26716830?dopt=AbstractPlus

1108. Mont MA, Jacobs JJ, Boggio LN et al. Preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011; 19:768-76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22134209?dopt=AbstractPlus

1109. Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv. 2019; 3:3898-3944. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=PMC6963238&blobtype=pdf http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31794602?dopt=AbstractPlus

1110. Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med. 2013; 368:513-23. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23388003?dopt=AbstractPlus