Vigabatrin (Monograph)

Brand name: Sabril

Drug class: GABA-mediated Anticonvulsants

Chemical name: (±) 4-amino-5-hexenoic acid

Molecular formula: C6H11NO2

CAS number: 60643-86-9

Warning

Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS):

FDA approved a REMS for vigabatrin to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks. The REMS may apply to one or more preparations of vigabatrin and consists of the following: elements to assure safe use and implementation system. See https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/. (See also Restricted Distribution Program under Dosage and Administration.)

Warning

- Permanent Vision Loss

-

Vigabatrin can cause permanent bilateral concentric visual field constriction, including tunnel vision that may result in disability.1 In some cases, vigabatrin also can damage the central retina and reduce visual acuity.1

-

Risk of vision loss increases with increasing dosage and cumulative exposure; however, no dosage or exposure is known to be without risk.1

-

Risk of new and worsening vision loss continues as long as vigabatrin is used and possibly after discontinuance.1

-

Baseline and periodic vision assessment recommended in patients receiving vigabatrin.1 However, such vision assessment cannot always prevent vision damage.1 3 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Cautions.)

-

Distribution of vigabatrin is restricted.1 71 (See Restricted Distribution Program under Dosage and Administration.)

Introduction

Anticonvulsant; irreversible inhibitor of GABA transaminase (GABA-T).1 6 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 24 25

Uses for Vigabatrin

Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Management (in combination with other anticonvulsants) of refractory complex partial seizures (CPS) in adults and pediatric patients ≥10 years of age who have not responded adequately to several alternative treatments.1 16 17 25 70

Use only in patients in whom potential benefits outweigh risk of vision loss.1 3 21 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

Do not use as first-line therapy.1 52

Infantile Spasms

Management (as monotherapy) of infantile spasms (IS; also known as West's syndrome) in pediatric patients 1 month–2 years of age for whom potential benefits outweigh risk of vision loss.1 3 5 6 7 21 24 25 52 55 58 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

Designated an orphan drug by FDA for this use.5

Duration of therapy was evaluated in a Canadian Pediatric Epilepsy Network (CPEN) study; 38 out of 68 infants with IS who responded to vigabatrin continued to receive the drug for a total of 6 months and were followed for an additional 18 months after drug discontinuance.1 69 Post hoc analysis indicated no observed IS recurrence in any of the infants.1

Many experts consider hormonal treatments (e.g., corticotropin [ACTH], prednisolone or prednisone, tetracosactide [not commercially available in the US]) and vigabatrin drugs of choice for treatment of IS.7 14 15 21 25 27 28 29 55 58 62 Vigabatrin is particularly effective in treating IS associated with tuberous sclerosis.6 8 14 15 25 27 29 58 62 Additional studies needed to determine optimal management of IS.8 58

Related/similar drugs

gabapentin, clonazepam, lamotrigine, lorazepam, pregabalin, topiramate, diazepam

Vigabatrin Dosage and Administration

General

-

Periodically assess patient's response to and continued need for therapy.1 38 Discontinue treatment if seizure control not apparent after an adequate trial of therapy.1 38 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

-

Avoid abrupt discontinuance; withdraw gradually to minimize potential for increased seizure frequency, unless concerns for patient safety require more rapid withdrawal.1 (See Dosage under Dosage and Administration and also see Discontinuance of Anticonvulsants under Cautions.)

-

Closely monitor for notable changes in behavior that could indicate emergence or worsening of suicidal thoughts or behavior or depression.1 3 10 11 12 (See Suicidality Risk under Cautions.)

Restricted Distribution Program

-

Distribution of vigabatrin is restricted in the US because of the risk of permanent vision loss (see REMS and also see Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions).1 3 71

-

Vigabatrin is only available in the US through the Sabril REMS program (formerly known as the SHARE [Support, Help, And Resources for Epilepsy] program).1 71 The previous REMS program for vigabatrin (SHARE) required periodic vision testing results to be documented through submission of ophthalmic assessment forms.71 In June 2016, FDA modified the REMS program in several areas, including removal of the requirement to complete and submit ophthalmic assessment forms.1 71 However, the periodic vision monitoring recommendations in the prescribing information for Sabril should still be followed.1 71

-

For further information, contact the Sabril REMS program at 888-457-4273 or visit [Web].1 71

Administration

Oral Administration

Administer orally (as oral solution for infantile spasms and as tablets or oral solution for refractory complex partial seizures) without regard to meals.1 25 Do not use tablets for treatment of infantile spasms because of difficulty administering them to infants or young children.1

Reconstitution of Oral Solution

Review and discuss the vigabatrin medication guide and instructions on proper reconstitution, administration, and dosing procedures with patients or caregivers and confirm their understanding.1

Use only water to dissolve the powder; mix thoroughly with a small spoon or other clean utensil until powder completely dissolves and solution is clear.1 4 Do not mix powder for oral solution with food or any other liquid.1 3 4

Empty entire contents of the appropriate number of packets (500 mg/packet) into a clean cup; dissolve with 10 mL of cold or room-temperature water per packet using the 10-mL oral syringe supplied by manufacturer to yield a final concentration of 50 mg/mL.1 4

For doses ≤500 mg, dissolve 1 packet with 10 mL of water; for doses of 501 mg–1 g, dissolve 2 packets with 20 mL of water; and for doses of 1–1.5 g, dissolve 3 packets with 30 mL of water.1 4 Discard resulting solution if not clear (or free of particles) and colorless.1

Use the 10-mL oral syringe supplied by manufacturer to withdraw volume of solution that will provide the appropriate dose; discard any remaining solution.1 4 Administer dose immediately following preparation.1 4

Dosage

Plasma vigabatrin concentrations not directly correlated with efficacy; therapeutic drug monitoring is not useful.1 16 19 21

Use the lowest dosage and shortest duration of therapy consistent with clinical objectives.1

Dosage regimen depends on the indication, age group, weight, and dosage form (tablets or oral solution).1

Pediatric Patients

Adjunctive Therapy of Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Oral

Pediatric patients 10–16 years of age weighing 25–60 kg: Initially, 500 mg daily (given as 250 mg twice daily).1 May increase total daily dosage in 500-mg increments at weekly intervals up to the recommended maintenance dosage of 2 g daily (given as 1 g twice daily).1

Pediatric patients ≥17 years of age or pediatric patients 10–16 years of age weighing >60 kg: May receive adult dosages.1 Initially, 1 g daily (given as 500 mg twice daily).1 25 May increase total daily dosage in 500-mg increments at weekly intervals up to the recommended dosage of 3 g daily (given as 1.5 g twice daily) depending on patient response.1 25

Dosage of 6 g daily was not more effective than 3 g daily and was associated with increased adverse effects.1 16

Periodically reassess patient response and continued need for therapy.1 38 If substantial clinical benefit not observed within 3 months of therapy initiation, withdraw therapy.1 38 If treatment failure is evident earlier, discontinue vigabatrin at that time.1 38

Reduce dosage gradually if discontinuing therapy.1 In clinical studies in adults, daily dosage was tapered by 1 g weekly.1 In a controlled study in pediatric patients with complex partial seizures, daily dosage was tapered by one-third every week for 3 weeks.1

Monotherapy of Infantile Spasms

Oral

Children 1 month–2 years of age: Initially, 50 mg/kg daily, administered in 2 divided doses (given as 25 mg/kg twice daily).1 25 May increase dosage in increments of 25–50 mg/kg daily every 3 days up to a maximum of 150 mg/kg daily (given as 75 mg/kg twice daily).1 25 (See Table 1.)

A spasm-free response often observed within the first 2–4 weeks of therapy; most responses observed within the first 2–3 months.6 7 21 24

|

Weight (kg) |

Starting Dosage (50 mg/kg daily) |

Maximum Dosage (150 mg/kg daily) |

|---|---|---|

|

3 |

1.5 mL twice daily |

4.5 mL twice daily |

|

4 |

2 mL twice daily |

6 mL twice daily |

|

5 |

2.5 mL twice daily |

7.5 mL twice daily |

|

6 |

3 mL twice daily |

9 mL twice daily |

|

7 |

3.5 mL twice daily |

10.5 mL twice daily |

|

8 |

4 mL twice daily |

12 mL twice daily |

|

9 |

4.5 mL twice daily |

13.5 mL twice daily |

|

10 |

5 mL twice daily |

15 mL twice daily |

|

11 |

5.5 mL twice daily |

16.5 mL twice daily |

|

12 |

6 mL twice daily |

18 mL twice daily |

|

13 |

6.5 mL twice daily |

19.5 mL twice daily |

|

14 |

7 mL twice daily |

21 mL twice daily |

|

15 |

7.5 mL twice daily |

22.5 mL twice daily |

|

16 |

8 mL twice daily |

24 mL twice daily |

Periodically reassess patient response and continued need for therapy.1 38 If substantial clinical benefit not observed within 2–4 weeks of therapy initiation, withdraw therapy.1 38 If treatment failure is evident earlier, discontinue vigabatrin at that time.1 38

Reduce dosage gradually if discontinuing therapy.1 In a controlled study in patients with infantile spasms, vigabatrin was tapered at a rate of 25–50 mg/kg daily every 3–4 days.1

Adults

Adjunctive Therapy of Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Oral

Initially, 1 g daily (given as 500 mg twice daily).1 25 May increase total daily dosage in 500-mg increments at weekly intervals up to the recommended dosage of 3 g daily (given as 1.5 g twice daily) depending on patient response.1 25

Dosage of 6 g daily was not more effective than 3 g daily and was associated with increased adverse effects.1 16

Periodically reassess patient response and continued need for therapy.1 38 If substantial clinical benefit not observed within 3 months of therapy initiation, withdraw therapy.1 38 If treatment failure is evident earlier, discontinue vigabatrin at that time.1 38

Reduce dosage gradually if discontinuing therapy.1 In clinical studies in adults, daily dosage was tapered by 1 g weekly.1

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Adjunctive Therapy of Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Oral

Pediatric patients 10–16 years of age weighing 25–60 kg: Manufacturer does not provide a specific maximum dosage.1 16

Pediatric patients ≥17 years of age or pediatric patients 10–16 years of age weighing >60 kg: Although manufacturer does not provide a specific maximum dosage, a dosage of 6 g daily was not more effective than 3 g daily in adults and was associated with increased adverse effects.1 16

Monotherapy of Infantile Spasms

Oral

Children 1 month–2 years of age: Maximum 150 mg/kg daily (given as 75 mg/kg twice daily).1

Adults

Adjunctive Therapy of Refractory Complex Partial Seizures

Oral

Although manufacturer does not provide a specific maximum dosage, a dosage of 6 g daily was not more effective than 3 g daily and was associated with increased adverse effects.1 16

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

No specific dosage recommendations at this time.1

Renal Impairment

Reduce dosage in adults and pediatric patients ≥10 years of age based on severity of renal impairment (see Table 2).1

|

Clcr (mL/min) |

Adjusted Dosage Regimen |

|---|---|

|

>50–80 (mild) |

Decrease dosage by 25% |

|

>30–50 (moderate) |

Decrease dosage by 50% |

|

>10–30 (severe) |

Decrease dosage by 75% |

In pediatric patients 10 to <12 years of age, use the following formula to estimate Clcr:1

Clcr = [K × height (in cm)] / serum creatinine (in mg/dL)

K for female child (<12 years) = 0.55

K for male child (<12 years) = 0.70

In pediatric patients ≥12 years of age and adults, use the following formula to estimate Clcr:1

Clcr male = [(140 - age) × weight (in kg)] / [72 × serum creatinine (in mg/dL)] Clcr female = 0.85 × Clcr male

Information about how to adjust the dosage of vigabatrin in infants with renal impairment is unavailable.1

Manufacturer does not provide specific dosage recommendations for patients undergoing hemodialysis.1 Some clinicians recommend administering vigabatrin following the hemodialysis session.53

Geriatric Patients

Carefully select dosage because of possible decreased renal function.1 Consider adjusting dosage or frequency of administration; may respond to a lower maintenance dosage than younger adults.1

Cautions for Vigabatrin

Contraindications

-

No known contraindications.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Permanent Vision Loss

Risk of visual field defects, including permanent vision loss; may occur at any time after beginning therapy and will not improve after discontinuance.1 3 21 22 24 25 34 35 37 52 62 64 65 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning.) In adults, manifestations include tunnel vision to within 10 degrees of visual fixation, which can lead to disability; in some cases, central retinal damage and decreased visual acuity may occur.1 23 25 64 Although visual field defects observed in pediatric patients,21 24 26 34 frequency and extent of vision loss are poorly characterized.1

Monitoring of vision by an ophthalmic professional recommended at baseline (≤4 weeks after start of therapy), at least every 3 months during treatment, and about 3–6 months following cessation of therapy.1 3 Because vision testing in infants is difficult, vision loss may not be detected until it is severe.1

If a patient cannot undergo vision testing, clinician may continue treatment according to clinical judgment after appropriate patient counseling.1 (See Restricted Distribution Program under Dosage and Administration.)

Unless benefits clearly outweigh risks, do not use in patients with, or at high risk of, other types of irreversible vision loss.1 Unless benefits clearly outweigh risks, avoid concurrent use with other drugs associated with serious adverse ophthalmic effects (e.g., retinopathy, glaucoma).1 (See Drugs associated with Serious Adverse Ophthalmic Effects under Interactions.)

Periodically reassess patient response to and continued need for therapy.1 Discontinue vigabatrin if substantial clinical benefit not evident within 2–4 weeks or within 3 months following therapy initiation in patients with infantile spasms or refractory complex partial seizures, respectively.1 If treatment failure becomes obvious earlier, discontinue drug at that time.1 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning.)

It is expected that, even with frequent vision monitoring, some vigabatrin-treated patients will develop severe vision loss.1 If vision loss is documented, consider drug discontinuance, balancing the benefit and risk of continued therapy.1

Other Warnings and Precautions

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Infants

Abnormal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) changes characterized by increased T2 signal and restricted diffusion in a symmetric pattern involving deep gray matter areas of the brain reported in some infants; these specific abnormalities not observed in older pediatric patients (≥3 years of age) and adults.1 3 21 22 23 25 30 31 32 51

MRI abnormalities generally are transient, resolve upon drug discontinuance, and may be dose-dependent.1 23 30 31 32 51 In a few patients, the abnormalities resolved despite continued therapy.1 31 51 Coincident motor abnormalities reported in some infants; however, causal relationship to drug not established.1 23 30 31

Routine MRI surveillance in pediatric patients with infantile spasms generally not recommended since long-term clinical sequelae of MRI changes are unknown.23 24 31 Manufacturer states that routine MRI surveillance is unnecessary in adults.1 If MRI abnormalities are observed, weigh benefits of continued therapy against potential risks of MRI surveillance and possible clinical consequences of the MRI changes.31

Neurotoxicity

Neuropathologic and neurobehavioral changes observed in animals receiving vigabatrin.1 22 31 32 33 Neurotoxicity (brain histopathology, neurobehavioral abnormalities) observed in animals exposed to vigabatrin during late gestation, neonatal, and/or juvenile periods of development; relationship of these findings with MRI abnormalities observed in vigabatrin-treated infants unknown.1 23 (See Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Infants under Cautions.)

Suicidality Risk

Increased risk of suicidality (suicidal ideation or behavior) observed in an analysis of studies using various anticonvulsants in patients with epilepsy, psychiatric disorders (e.g., bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety), and other conditions (e.g., migraine, neuropathic pain); risk in patients receiving anticonvulsants (0.43%) was approximately twice that in patients receiving placebo (0.24%).1 10 11 12 Increased suicidality risk was observed ≥1 week after initiation of anticonvulsant therapy and continued through 24 weeks.10 11 Risk was higher for patients with epilepsy compared with those receiving anticonvulsants for other conditions.1 10

Closely monitor all patients currently receiving or beginning anticonvulsant therapy for changes in behavior that may indicate emergence or worsening of suicidal thoughts or behavior or depression.1 10 11 12 Anxiety, agitation, hostility, insomnia, and mania may be precursors to emerging suicidality.10

Balance risk of suicidality with risk of untreated illness.1 10 Epilepsy and other illnesses treated with anticonvulsants are themselves associated with morbidity and mortality and an increased risk of suicidality.1 12 If suicidal thoughts or behavior emerge during anticonvulsant therapy, consider whether these symptoms may be related to the illness itself.1 12 (See Advice to Patients.)

Discontinuance of Anticonvulsants

Abrupt withdrawal of anticonvulsants may result in increased seizure frequency in patients with seizure disorders.1 When discontinuing therapy, withdraw vigabatrin gradually.1 However, if discontinuance is necessary because of serious adverse effects, may consider prompt withdrawal of the drug.1 (See Dosage under Dosage and Administration.)

Anemia

Anemia and/or potentially clinically important hematology changes involving hemoglobin, hematocrit, and/or RBC indices reported.1

Somnolence and Fatigue

Somnolence and fatigue reported in adult and pediatric patients, sometimes requiring discontinuance.1

May impair mental and/or physical abilities required to perform potentially hazardous tasks such as driving or operating machinery.1 (See Advice to Patients.)

Peripheral Neuropathy

Peripheral neuropathy symptoms reported in adults.1 Initial manifestations include numbness or tingling in the toes or feet, signs of reduced distal lower limb vibration or position sensation, and/or progressive loss of reflexes starting at the ankles.1

Studies in pediatric patients not adequately designed to assess peripheral neuropathy symptoms; however, incidence of symptoms in controlled pediatric studies appeared similar with vigabatrin and placebo.1

Weight Gain

Weight gain reported in adult and pediatric patients;1 19 22 25 usually was self-limiting in clinical trials,16 but long-term effects of such weight gain not known.1 Weight gain not apparently related to occurrence of edema (see Edema under Cautions).1

Edema

Vigabatrin causes edema in adults.1 Pediatric clinical studies not designed to assess edema; however, observed incidence of edema appeared similar with vigabatrin and placebo.1

No apparent association between edema and adverse cardiovascular effects (e.g., hypertension, CHF) in adults.1 Edema not associated with laboratory changes suggesting deterioration of renal or hepatic function.1

Laboratory Test Interferences

Decreases plasma ALT and AST activity in ≤90% of patients, sometimes to undetectable levels.1 16 May preclude use of these tests, particularly ALT, to detect early hepatic injury.1 24

May increase amount of amino acids in the urine, possibly resulting in false positive test results for certain rare genetic metabolic disorders (e.g., alpha aminoadipic aciduria).1 56 Consider obtaining urine for metabolic evaluation prior to initiating therapy.56

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

North American Antiepileptic Drug (NAAED) Pregnancy Registry (for patients) at 888-233-2334 or [Web].1

Lactation

Distributed into milk.1 44 45 Discontinue nursing or the drug.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy for adjunctive therapy of refractory complex partial seizures established in pediatric patients 10–16 years of age.1 70 Indicated for such use in pediatric patients ≥10 years of age who have not responded adequately to several alternative treatments.1 Adverse effects in this pediatric population are similar to those observed in adults.1

Safety and efficacy for treatment of complex partial seizures in pediatric patients <10 years of age not established;1 risks (e.g., vision loss) generally appear to outweigh benefits of such use.23 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

Indicated as monotherapy in pediatric patients 1 month–2 years of age with infantile spasms for whom potential benefits outweigh the risk of vision loss; safety and efficacy for treating infantile spasms not established outside this age group.1 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

Abnormal MRI signal changes observed in some infants receiving vigabatrin for infantile spasms.1 31 (See Magnetic Resonance Imaging Abnormalities in Infants and also see Neurotoxicity under Cautions.)

Geriatric Use

Insufficient experience in patients ≥65 years of age to determine whether geriatric patients respond differently than younger adults.1

Moderate to severe sedation and confusion reported in several patients >65 years of age with reduced renal function (Clcr <50 mL/minute).1 Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in response.1

Reduced renal function more likely in geriatric patients.1 Carefully select dosage; renal function monitoring may also be useful.1 (See Geriatric Patients under Dosage and Administration and also see Special Populations under Pharmacokinetics.)

Hepatic Impairment

Pharmacokinetics in patients with hepatic impairment not evaluated.1 24

Suppresses ALT and AST activity.1 24 (See Laboratory Test Interferences under Cautions.)

Renal Impairment

Decreased clearance; use with caution.1 22 24 Adjust dosage in pediatric patients ≥10 years of age and adults and monitor for dose-related adverse effects.1 24 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration and also see Special Populations under Pharmacokinetics.) Information about how to adjust vigabatrin dosage in infants is not available.1

Race

Race-related pharmacokinetic differences not specifically evaluated.1 Limited data suggest that renal clearance may be lower in Japanese than in Caucasian populations.1

Common Adverse Effects

Causes permanent vision damage in a high percentage of patients.1 (See Permanent Vision Loss under Boxed Warning and also under Cautions.)

Adults (>16 years of age) with refractory complex partial seizures: Headache, fatigue, somnolence, dizziness, nystagmus, tremor, convulsion, nasopharyngitis, blurred vision, diplopia, memory impairment, insomnia, irritability, upper respiratory tract infection, abnormal coordination, pharyngolaryngeal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, constipation, upper abdominal pain, increased weight, dysmenorrhea, depression, confusional state, asthenia, peripheral edema, fever/pyrexia, influenza, arthralgia, back pain, pain in extremities, disturbance in attention, sensory disturbance, hyporeflexia, paresthesia.1 16 22 25

Pediatric patients 10–16 years of age with refractory complex partial seizures: Increased weight, upper respiratory tract infection, fatigue, abnormal behavior, diarrhea, influenza, otitis media, somnolence, tremor, aggression, diplopia, nystagmus.1

Pediatric patients with infantile spasms: Somnolence, bronchitis, ear infection, acute otitis media.1 7

Drug Interactions

Not extensively metabolized by hepatic CYP isoenzymes.1

Induces CYP2C9; does not appear to induce or inhibit other hepatic CYP isoenzymes.1 19 24

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

Substrates of CYP2C9: potential pharmacokinetic interaction (decreased plasma substrate concentrations).1 19 22 24 25 42

Substrates of other CYP isoenzymes: clinically important interactions unlikely.1 19 22 24 25 42

Drugs associated with Serious Adverse Ophthalmic Effects

Avoid concurrent use with other drugs associated with serious adverse ophthalmic effects (e.g., retinopathy, glaucoma) unless benefits clearly outweigh risks.1 54

Specific Drugs and Laboratory Tests

|

Drug or Test |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Alcohol |

Pharmacokinetic interaction not observed;1 24 no evidence of additive CNS depressant effects42 |

|

|

Carbamazepine |

Both increased48 49 and decreased plasma carbamazepine concentrations46 49 reported;46 48 49 no apparent effect on plasma vigabatrin concentrations1 |

Monitor plasma carbamazepine concentrations; adjust dosage if necessary46 48 49 |

|

Clonazepam |

Increased peak plasma concentrations and decreased time to peak concentration of clonazepam; no substantial change in plasma concentrations of vigabatrin1 No evidence of additive CNS effects42 |

|

|

Clorazepate |

No apparent effect on plasma vigabatrin concentrations1 |

|

|

Contraceptives, oral |

No substantial effect on CYP3A4-mediated metabolism of ethinyl estradiol/levonorgestrel;1 50 unlikely to affect efficacy of steroid oral contraceptives1 Pharmacokinetics of vigabatrin not substantially affected1 50 |

|

|

Felbamate |

Slightly increased AUC of vigabatrin; no change in plasma concentrations or AUC of felbamate59 60 Clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely59 60 |

|

|

Phenobarbital |

Clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 16 19 |

|

|

Phenytoin |

Moderate decrease in total plasma phenytoin concentrations (by 16–20%), probably due to induction of CYP2C91 21 22 25 42 |

Routine phenytoin dosage adjustment not required; adjust dosage if clinically indicated1 19 |

|

Primidone |

Clinically important pharmacokinetic interaction unlikely1 16 19 |

|

|

Rufinamide |

Slight to moderate decrease in plasma concentrations of rufinamide47 |

Monitor carefully when initiating or discontinuing either anticonvulsant; adjust rufinamide dosage if necessary47 |

|

Tests for ALT and AST activity |

Possible suppression of ALT and AST activity1 |

Consider that these tests, particularly ALT, may not be useful for detection of early hepatic injury1 24 |

|

Tests for amino acids in urine |

Possible increased amino acid concentrations in urine; may result in false positive tests for certain rare genetic metabolic disorders (e.g., alpha aminoadipic aciduria)1 56 |

Consider obtaining urine for metabolic evaluation prior to initiating vigabatrin therapy56 |

|

Valproic acid |

Decreased plasma valproate sodium concentrations,1 but no substantial effect on vigabatrin concentrations1 Clinically important pharmacokinetic Interaction unlikely1 19 24 |

Vigabatrin Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly and essentially completely absorbed following oral administration.1 21 22 24 Commercially available tablets and oral solution are bioequivalent, with an absolute oral bioavailability of 60–70%.1 22

Peak plasma concentrations generally occur within approximately 2.5 hours in infants (5 months–2 years of age) and 1 hour in older pediatric patients (10–16 years of age) and adults following oral administration.1 22

Little accumulation occurs with multiple dosing in adult and pediatric patients.1

Duration

Duration of vigabatrin’s anticonvulsant effect is about 4–6 days; duration does not directly correlate with plasma concentration, possibly reflecting time required for GABA-T resynthesis.1 22 24

Food

Food decreases peak plasma concentrations by 33% and increases time to peak concentrations, but does not affect systemic exposure.1 24

Special Populations

Systemic exposure increased by approximately 30%, twofold, and 4.5-fold in adults with mild, moderate, and severe renal impairment, respectively.1

Distribution

Extent

Crosses the placenta.44 Distributed into milk,1 44 45 probably in small amounts.44

Plasma Protein Binding

Not appreciably bound to plasma proteins.1 21 22

Elimination

Metabolism

Not extensively metabolized.1 22

Elimination Route

Principally excreted in urine (95% of orally administered dose recovered over 72 hours), with unchanged drug accounting for 80% of the recovered dose.1 21 22

Half-life

Adults: About 10.5 hours.1 22 24

Pediatric patients 10–16 years of age: About 9.5 hours.1

Infants (5 months–2 years of age): About 5.7 hours.1 22 24

Special Populations

In adults with mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment, terminal half-life is increased by 55%, twofold, or 3.5-fold, respectively.1

Effect of hemodialysis on clearance not adequately studied.1 57 In case reports, hemodialysis reduced plasma concentrations by 40–60%.1 53 57

Pharmacokinetics in patients with hepatic impairment not evaluated.1

In individuals >65 years of age, renal clearance is reduced by 36% compared with younger individuals.1

Stability

Storage

Oral

Powder for Oral Solution

20–25°C.1

Tablets

20–25°C.1

Actions

-

Structural analog of GABA, the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the CNS.17 18 20 21 22

-

Exact mechanism of antiseizure effect unknown; thought to be related to preferential and irreversible inhibition of GABA-T, the enzyme responsible for the degradation of GABA, and the resultant increase in GABA concentrations in the CNS.1 6 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 24 25

-

Following oral administration, CNS and blood concentrations of GABA increase in a dose-related matter, but there is no direct correlation between plasma concentrations and drug efficacy.1 21 22 24 25

-

Highly selective and specific for GABA-T; does not affect other enzymatic pathways in the GABA system.22

-

Commercially available as a racemic mixture of 2 enantiomers; the S enantiomer is pharmacologically active and the R enantiomer is inactive.24 44 57

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of advising patients or caregivers to read the manufacturer's patient information (medication guide).1 (See REMS and also see Restricted Distribution Program under Dosage and Administration.)

-

Risk of permanent vision loss; peripheral vision field loss potentially may interfere with ability to drive.1 3 52 Importance of advising patients or caregivers that vision monitoring, including an assessment of peripheral vision, is recommended at baseline and periodically during treatment.1 Importance of patients and caregivers understanding that visual testing may not prevent the occurrence of visual impairment, but can allow for early detection and intervention.1 3 Importance of patients or caregivers notifying a clinician immediately if changes in vision are suspected.1 3

-

Importance of taking only as prescribed.1 When using oral solution, confirm that the patient or caregivers understand instructions for reconstitution and administration of correct dosage.1

-

Importance of informing caregivers about the possibility that infants receiving vigabatrin may develop abnormal MRI signal changes of unknown clinical importance.1 31

-

Risk of suicidality (anticonvulsants, including vigabatrin, may increase risk of suicidal thoughts or actions in about 1 in 500 people).1 10 12 Importance of patients, family, and caregivers being alert to day-to-day changes in mood, behavior, and actions and immediately informing clinician of any new or worrisome behaviors (e.g., talking or thinking about wanting to hurt oneself or end one’s life, withdrawing from friends and family, becoming depressed or experiencing worsening of existing depression, becoming preoccupied with death and dying, giving away prized possessions).1 10

-

Advise patients or caregivers not to abruptly discontinue vigabatrin therapy without first consulting their clinician since stopping the drug suddenly can cause serious problems, including increased seizures.1 3

-

Risk of drowsiness and fatigue.1 3 Importance of advising patients not to drive or operate other complex machinery until they have become accustomed to the drug's effects.1 3

-

Importance of informing clinicians of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary or herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illness (e.g., kidney disease, vision problems, depression or other mood disorders) or family history of suicidality or bipolar disorder.1 3

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1 3 Importance of clinicians informing women about the existence of and encouraging enrollment in pregnancy registries (see Pregnancy under Cautions).1 3

-

Importance of informing patients or caregivers of other important precautionary information.1 3 (See Cautions.)

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

Distribution of vigabatrin is restricted.1 71 (See Restricted Distribution Program under Dosage and Administration.)

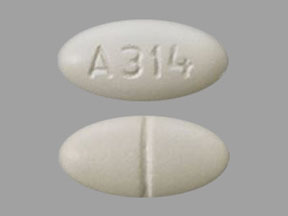

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Powder for oral solution |

500 mg |

Sabril (available in packets) |

Lundbeck |

|

Tablets, film-coated |

500 mg |

Sabril (scored) |

Lundbeck |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2024, Selected Revisions June 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

1. Lundbeck LLC. Sabril (vigabatrin) tablets and powder for oral solution prescribing information. Deerfield, IL; 2016 Jun.

3. Lundbeck. Sabril (vigabatrin) tablets and powder for oral solution medication guide. Deerfield, IL; 2016 Jun.

4. Lundbeck. Sabril (vigabatrin) powder for oral solution instructions for use. Deerfield, IL; 2013 Oct.

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Orphan designations pursuant to Section 526 of the Federal Food and Cosmetic Act as amended by the Orphan Drug Act (PL. 97-414). Rockville, MD; [March 9, 2010]. From FDA web site. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/index.cfm

6. Elterman RD, Shields WD, Mansfield KA et al. Randomized trial of vigabatrin in patients with infantile spasms. Neurology. 2001; 57:1416-21. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11673582?dopt=AbstractPlus

7. Appleton RE, Peters AC, Mumford JP et al. Randomised, placebo-controlled study of vigabatrin as first-line treatment of infantile spasms. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:1627-33. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10565592?dopt=AbstractPlus

8. Hancock EC, Osborne JP, Edwards SW. Treatment of infantile spasms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001770. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001770.pub2.

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Alert: Information for healthcare professionals: suicidal behavior and ideation and antiepileptic drugs. Rockville, MD; 2008 Jan 31; updated 2008 Dec 16. From the FDA website. Accessed 2010 Mar 5. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm100192.htm

11. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA News: FDA alerts health care providers to risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior with antiepileptic medications. Rockville, MD; 2008 Jan 31. From the FDA website. Accessed 2010 Mar 12. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm100200.htm

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Suicidal behavior and ideation and antiepileptic drugs: update 5/5/2009. Rockville, MD; 2009 May 5. From the FDA website. Accessed 2010 Mar 12. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm100190.htm

14. Mackay MT, Weiss SK, Adams-Webber T et al. Practice parameter: medical treatment of infantile spasms: report of the American Academy of Neurology and the Child Neurology Society. Neurology. 2004; 62:1668-81. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15159460?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2937178&blobtype=pdf

15. National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. London, UK: Royal College of General Practitioners; 2004 Oct. Accessed 2010 March 20. http://www.guidelines.gov

16. Dean C, Mosier M, Penry K. Dose-response study of vigabatrin as add-on therapy in patients with uncontrolled complex partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:74-82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9924905?dopt=AbstractPlus

17. French JA, Mosier M, Walker S et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of vigabatrin three g/day in patients with uncontrolled complex partial seizures. Vigabatrin Protocol 024 Investigative Cohort. Neurology. 1996; 46:54-61. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8559421?dopt=AbstractPlus

18. Hemming K, Maguire MJ, Hutton JL et al. Vigabatrin for refractory partial epilepsy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD007302. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007302.

19. Bruni J, Guberman A, Vachon L et al. Vigabatrin as add-on therapy for adult complex partial seizures: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study. The Canadian Vigabatrin Study Group. Seizure. 2000; 9:224-32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10777431?dopt=AbstractPlus

20. Beran RG, Berkovic SF, Buchanan N et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of vigabatrin 2 g/day and 3 g/day in uncontrolled partial seizures. Seizure. 1996; 5:259-65. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8952010?dopt=AbstractPlus

21. Willmore LJ, Abelson MB, Ben-Menachem E et al. Vigabatrin: 2008 update. Epilepsia. 2009; 50:163-73. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19230067?dopt=AbstractPlus

22. Tolman JA, Faulkner MA. Vigabatrin: a comprehensive review of drug properties including clinical updates following recent FDA approval. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009; 10:3077-89. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19954276?dopt=AbstractPlus

23. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Application number 20-427: Summary Review/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/020427s000_SumR.pdf. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2009/020427s000_SumR.pdf

24. Lundbeck Inc: Personal communication.

25. Anon. Vigabatrin (Sabril) for epilepsy. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2010; 52: 14-6.

26. Lux AL, Edwards SW, Hancock E et al. The United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study comparing vigabatrin with prednisolone or tetracosactide at 14 days: a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004; 364:1773-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15541450?dopt=AbstractPlus

27. Vigevano F, Cilio MR. Vigabatrin versus ACTH as first-line treatment for infantile spasms: a randomized, prospective study. Epilepsia. 1997; 38:1270-4. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9578521?dopt=AbstractPlus

28. Granström ML, Gaily E, Liukkonen E. Treatment of infantile spasms: results of a population-based study with vigabatrin as the first drug for spasms. Epilepsia. 1999; 40:950-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10403219?dopt=AbstractPlus

29. Chiron C, Dumas C, Jambaqué I et al. Randomized trial comparing vigabatrin and hydrocortisone in infantile spasms due to tuberous sclerosis. Epilepsy Res. 1997; 26:389-95. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9095401?dopt=AbstractPlus

30. Milh M, Villeneuve N, Chapon F et al. Transient brain magnetic resonance imaging hyperintensity in basal ganglia and brain stem of epileptic infants treated with vigabatrin. J Child Neurol. 2009; 24:305-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19258289?dopt=AbstractPlus

31. Wheless JW, Carmant L, Bebin M et al. Magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities associated with vigabatrin in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2009; 50:195-205. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19054414?dopt=AbstractPlus

32. Pearl PL, Vezina LG, Saneto RP et al. Cerebral MRI abnormalities associated with vigabatrin therapy. Epilepsia. 2009; 50:184-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18783433?dopt=AbstractPlus

33. Cohen JA, Fisher RS, Brigell MG et al. The potential for vigabatrin-induced intramyelinic edema in humans. Epilepsia. 2000; 41:148-57. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10691111?dopt=AbstractPlus

34. Wild JM, Ahn HS, Baulac M et al. Vigabatrin and epilepsy: lessons learned. Epilepsia. 2007; 48:1318-27. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17635558?dopt=AbstractPlus

35. Eke T, Talbot JF, Lawden MC. Severe persistent visual field constriction associated with vigabatrin. BMJ. 1997; 314:180-1. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9022432?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2125673&blobtype=pdf

36. Gaily E, Jonsson H, Lappi M. Visual fields at school-age in children treated with vigabatrin in infancy. Epilepsia. 2009; 50:206-16. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19215279?dopt=AbstractPlus

37. Wild JM, Chiron C, Ahn H et al. Visual field loss in patients with refractory partial epilepsy treated with vigabatrin: final results from an open-label, observational, multicentre study. CNS Drugs. 2009; 23:965-82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19845417?dopt=AbstractPlus

38. Lundbeck. Sabril (vigabatrin): Official US site for healthcare professionals. From Sabril web site. 2016 Aug 1. http://sabril.net/hcp/

39. Sanofi-Aventis. Sabril (vigabatrin) sachets 0.5 g and tablets 500 mg summary of product characteristics. 2009 Apr 16.

40. Levinson DF, Devinsky O. Psychiatric adverse events during vigabatrin therapy. Neurology. 1999; 53:1503-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10534259?dopt=AbstractPlus

41. Rimmer EM, Richens A. Interaction between vigabatrin and phenytoin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1989; 27 (Suppl. 1):27S-33S. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2757906?dopt=AbstractPlus

42. Richens A. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interactions during treatment with vigabatrin. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995; 162:43-6.

43. Perucca E, Cloyd J, Critchley D et al. Rufinamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and concentration-response relationships in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008; 49:1123-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18503564?dopt=AbstractPlus

44. Tran A, O'Mahoney T, Rey E et al. Vigabatrin: placental transfer in vivo and excretion into breast milk of the enantiomers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1998; 45:409-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9578192?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1873959&blobtype=pdf

45. Bar-Oz B, Nulman I, Koren G et al. Anticonvulsants and breast-feeding: a critical review. Paediatr Drugs. 2000; 2:113-26. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10937463?dopt=AbstractPlus

46. Sánchez-Alcaraz A, Quintana MB, Lopez E et al. Effect of vigabatrin on the pharmacokinetics of carbamazepine. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002; 27:427-30. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12472982?dopt=AbstractPlus

47. Perucca E, Cloyd J, Critchley D et al. Rufinamide: clinical pharmacokinetics and concentration-response relationships in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2008; 49:1123-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18503564?dopt=AbstractPlus

48. Jedrzejczak J, Dlawichowska E, Owczarek K et al. Effect of vigabatrin on carbamazepine blood serum levels in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2000; 39:115-20. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10759299?dopt=AbstractPlus

49. Baxter K, ed. Carbamazepine + vigabatrin. Stockley's Drug Interactions. [online] London: The Pharmaceutical Press; updated 2009 Dec 2. From the Medicines Complete website. Accessed 2010 Apr 20. http://www.medicinescomplete.com

50. Bartoli A, Gatti G, Cipolla G et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effect of vigabatrin on in vivo parameters of hepatic microsomal enzyme induction and on the kinetics of steroid oral contraceptives in healthy female volunteers. Epilepsia. 1997; 38:702-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9186253?dopt=AbstractPlus

51. Dracopoulos A, Widjaja E, Raybaud C et al. Vigabatrin-associated reversible MRI signal changes in patients with infantile spasms. Epilepsia. 2010; 51:1297-304. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20384718?dopt=AbstractPlus

52. Krauss GL. Evaluating risks for vigabatrin treatment. Epilepsy Curr. 2009 Sep-Oct; 9:125-9.

53. Bachmann D, Ritz R, Wad N et al. Vigabatrin dosing during hemodialysis. Seizure. 1996; 5:239-42. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8902928?dopt=AbstractPlus

54. Li J, Tripathi RC, Tripathi BJ. Drug-induced ocular disorders. Drug Saf. 2008; 31:127-41. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18217789?dopt=AbstractPlus

55. Elterman RD, Shields WD, Bittman RM et al. Vigabatrin for the treatment of infantile spasms: final report of a randomized trial. J Child Neurol. 2010; :Apr 19 [epub ahead of print]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20404353?dopt=AbstractPlus

56. Lahat E, Ben-Zeev B, Zlotnik J et al. Aminoaciduria resulting from vigabatrin administration in children with epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol. 1999; 21:460-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10428431?dopt=AbstractPlus

57. Jacqz-Aigrain E, Guillonneau M, Rey E et al. Pharmacokinetics of the S(+) and R(-) enantiomers of vigabatrin during chronic dosing in a patient with renal failure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997; 44:183-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9278207?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2042814&blobtype=pdf

58. Kossoff EH. Infantile spasms. The Neurologist. 2010; 16:69-75. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20220440?dopt=AbstractPlus

59. Reidenberg P, Glue P, Banfield C et al. Pharmacokinetic interaction studies between felbamate and vigabatrin. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995; 40:157-60. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8562299?dopt=AbstractPlus http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1365176&blobtype=pdf

60. Baxter K, ed. Vigabatrin + felbamate. Stockley's Drug Interactions. [online] London: The Pharmaceutical Press; updated 2009 Oct 12. From the Medicines Complete website. Accessed 2010 Apr 20. http://www.medicinescomplete.com

61. Yang T, Pruthi S, Geyer JR et al. MRI changes associated with vigabatrin treatment mimicking tumor progression. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010; :Jun 8 [epub ahead of print]. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20533524?dopt=AbstractPlus

62. Pellock JM, Hrachovy R, Shinnar S et al. Infantile spasms: A U.S. consensus report. Epilepsia. 2010; :. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/picrender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3058797&blobtype=pdf

63. Sergott RC, Wheless JW, Smith MC et al. Evidence-based review of recommendations for visual function testing in patients treated with vigabatrin. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2010; 34:20-35.

64. Miller NR, Johnson MA, Paul SR et al. Visual dysfunction in patients receiving vigabatrin: clinical and electrophysiologic findings. Neurology. 1999; 53:2082-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10599785?dopt=AbstractPlus

65. Malmgren K, Ben-Menachem E, Frisén L. Vigabatrin visual toxicity: evolution and dose dependence. Epilepsia. 2001; 42:609-15. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11380567?dopt=AbstractPlus

66. Dalla Bernardina B, Fontana E, Vigevano F et al. Efficacy and tolerability of vigabatrin in children with refractory partial seizures: a single-blind dose-increasing study. Epilepsia. 1995; 36:687-91. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7555986?dopt=AbstractPlus

67. Luna D, Dulac O, Pajot N et al. Vigabatrin in the treatment of childhood epilepsies: a single-blind placebo-controlled study. Epilepsia. 1989 Jul-Aug; 30:430-7.

68. Walker SD, Kälviäinen R. Non-vision adverse events with vigabatrin therapy. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 2011; :72-82. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22061182?dopt=AbstractPlus

69. Bitton JY, Sauerwein HC, Weiss SK et al. A randomized controlled trial of flunarizine as add-on therapy and effect on cognitive outcome in children with infantile spasms. Epilepsia. 2012; 53:1570-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22889307?dopt=AbstractPlus

70. Lundbeck Inc. Data on file. Deerfield, IL.

71. US Food and Drug Administration. Sabril REMS program risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS). Last modified/revised 2016 Jun. From FDA website. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/rems/Sabril_2016_06_27_Full.pdf

Frequently asked questions

More about vigabatrin

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (2)

- Drug images

- Latest FDA alerts (1)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: gamma-aminobutyric acid analogs

- Breastfeeding

- En español