quiNINE (Monograph)

Brand name: Qualaquin

Drug class: Antimalarials

VA class: AP101

Chemical name: (8S,9R)-6′-Methoxycinchonan-9-ol

Molecular formula: C20H24N2O2

CAS number: 60-93-5

Warning

-

Serious and life-threatening hematologic reactions, including thrombocytopenia and hemolytic uremic syndrome/thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (HUS/TTP), may occur if quinine used for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps† [off-label].180 183 186

-

Chronic renal impairment associated with TTP reported.180 183 186

-

Known risks associated with use of quinine, in the absence of evidence of safety and efficacy of the drug for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps† [off-label], outweigh any potential benefits for this unlabeled indication.180 183 186 (See Use for Treatment or Prevention of Nocturnal Leg Cramps under Cautions.)

Introduction

Antimalarial; alkaloid obtained from bark of the cinchona tree.185

Uses for quiNINE

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by Plasmodium falciparum.134 143 144 180 183 186 Also used for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. vivax† [off-label]134 143 144 173 and treatment of uncomplicated malaria when plasmodial species not identified† [off-label].134 143 144 173

Designated an orphan drug by FDA for treatment of malaria.179 Since malaria is a life-threatening infection, FDA states that potential benefits of the drug outweigh associated risks and justify its use for treatment of malaria.182

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or treatment of uncomplicated malaria when plasmodial species not identified, CDC recommends fixed combination of atovaquone and proguanil (atovaquone/proguanil), fixed combination of artemether and lumefantrine (artemether/lumefantrine), or regimen of quinine in conjunction with doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin.143 144 If quinine regimen used, concomitant doxycycline or tetracycline generally preferred instead of concomitant clindamycin since more efficacy data exist regarding antimalarial regimens that include tetracyclines.143

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-susceptible P. falciparum, P. malariae, or P. knowlesi or treatment of uncomplicated malaria when plasmodial species not identified and infection acquired in areas where chloroquine resistance not reported, CDC recommends chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine).143 144 Alternatively, CDC states that any of the regimens recommended for treatment of uncomplicated chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria may be used if preferred, more readily available, or more convenient.143 144

For treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. vivax† [off-label], CDC recommends regimen of quinine and doxycycline (or tetracycline) given in conjunction with primaquine, atovaquone/proguanil given in conjunction with primaquine, or mefloquine given in conjunction with primaquine.144 143 Because quinine, doxycycline (or tetracycline), atovaquone/proguanil, and mefloquine active only against asexual erythrocytic forms of Plasmodium (not exoerythrocytic stages), 14-day regimen of primaquine indicated to prevent delayed primary attacks or relapse and provide a radical cure whenever any of these drugs used for treatment of P. vivax or P. ovale malaria.134 143

Pediatric patients with uncomplicated malaria generally can receive same treatment regimens recommended for adults using age- and weight-appropriate drugs and dosages.143 144 For treatment of uncomplicated chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in children <8 years of age, atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine usually recommended; mefloquine can be considered if no other options available.144 If a quinine regimen used in children <8 years of age, CDC states a 7-day regimen of quinine alone can be used (regardless of where infection was acquired) or quinine can be given in conjunction with clindamycin, since children <8 years of age generally should not receive tetracyclines.143 In rare instances, doxycycline or tetracycline can be used in conjunction with quinine in children <8 years of age if other treatment options not available or not tolerated and if potential benefits of including a tetracycline outweigh risks.143 For treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax malaria in children <8 years of age, CDC recommends mefloquine given in conjunction with primaquine.143 144 Alternatively, if mefloquine not available or not tolerated and if potential benefits outweigh risks, atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine can be used for treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax in this age group.143 144

Pregnant women with uncomplicated malaria caused by P. malariae, P. vivax, P. ovale, or chloroquine-susceptible P. falciparum should receive prompt treatment with chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine).143 CDC recommends that pregnant women with uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum receive prompt treatment with mefloquine or a regimen of quinine and clindamycin;143 mefloquine recommended for those with uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. vivax.143 Although tetracyclines generally contraindicated in pregnant women, in rare circumstances when other treatment options not available or not tolerated and if potential benefits outweigh risks, CDC states that regimen of quinine and doxycycline (or tetracycline) may be used.143 (See Pregnancy under Cautions.) Alternatively, atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine can be considered for treatment of uncomplicated malaria caused by chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum in pregnant women when other treatment options not available or not tolerated and if potential benefits outweigh risks.143 Pregnant women with P. vivax or P. ovale malaria should receive chloroquine prophylaxis for the duration of the pregnancy and receive primaquine after delivery to provide a radical cure.143 144

Assistance with diagnosis or treatment of malaria available from CDC Malaria Hotline at 770-488-7788 or 855-856-4713 from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time or CDC Emergency Operation Center at 770-488-7100 after hours and on weekends and holidays.143 144

Treatment of Severe Malaria

Used in conjunction with doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin for follow-up treatment of severe or complicated malaria†.143 144

Severe malaria usually caused by P. falciparum and requires initial aggressive treatment with a parenteral antimalarial regimen initiated as soon as possible after diagnosis.143 144 200

For treatment of severe malaria in adults and children, CDC recommends an initial regimen of IV quinidine in conjunction with doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin (administered orally or IV as tolerated).143 144 After parasitemia reduced to <1% and oral therapy tolerated, IV quinidine can be discontinued and oral quinine initiated to complete 7 or 3 days of total quinidine and quinine therapy as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria was acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).143 144

If IV quinidine unavailable or cannot be used for initial treatment because of adverse effects or contraindications, parenteral artesunate may be available from CDC under an investigational new drug (IND) protocol for emergency initial treatment of severe malaria.143 144

Assistance with diagnosis or treatment of malaria and assistance obtaining quinidine or artesunate for treatment of severe malaria is available by contacting CDC Malaria Hotline at 770-488-7788 or 855-856-4713 from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time or CDC Emergency Operation Center at 770-488-7100 after hours and on weekends and holidays.143

Presumptive Self-treatment of Malaria

Regimen of quinine in conjunction with doxycycline has been recommended by some clinicians for presumptive self-treatment of malaria† in travelers.134

Not approved by FDA for presumptive self-treatment of malaria in travelers180 and not recommended by CDC for such treatment.115

For presumptive self-treatment of malaria in travelers, CDC and other experts recommend atovaquone/proguanil or artemether/lumefantrine.115 134

Prevention of Malaria

Not approved by FDA for prevention (prophylaxis) of malaria180 and not included in current CDC recommendations for prevention of malaria.115

CDC and other clinicians recommend other antimalarials (e.g., chloroquine [or hydroxychloroquine], atovaquone/proguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine) for prevention of malaria caused by susceptible plasmodia.115 134

Information on risk of malaria in specific countries and mosquito avoidance measures and recommendations regarding whether prevention of malaria indicated and choice of antimalarials for prevention are available from CDC at [Web] and [Web].115

Babesiosis

Treatment of babesiosis† caused by Babesia microti.102 103 105 134 178 181

IDSA states that all patients with active babesiosis (i.e., symptoms of viral-like infection and identification of babesial parasites in blood smears or by polymerase chain reaction [PCR] amplification of babesial DNA) should receive anti-infective treatment because of the risk of complications; however, symptomatic patients whose serum contains antibody to babesia but whose blood lacks identifiable babesial parasites on smear or babesial DNA by PCR should not receive treatment.178 Treatment not recommended initially for asymptomatic individuals, regardless of results of serologic examination, blood smears, or PCR, but should be considered if parasitemia persists for >3 months.178

When anti-infective treatment of babesiosis indicated, IDSA and other clinicians recommend a regimen of quinine and clindamycin or a regimen of atovaquone and azithromycin.105 134 178 181

The quinine and clindamycin regimen may be preferred for severe babesiosis.178 However, there is some evidence that, in patients with mild or moderate illness, the atovaquone and azithromycin regimen may be as effective and better tolerated than the quinine and clindamycin regimen.105 134 178 181 Consider use of exchange transfusions, especially in severely ill patients with high levels of parasitemia (≥10%), significant hemolysis, or compromised renal, hepatic, or pulmonary function.105 134 178

B. microti is transmitted by Ixodes scapularis ticks, which also may be simultaneously infected with and transmit Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) and Anaplasma phagocytophilum (causative agent of human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis [HGA, formerly known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis]).105 178 Consider possibility of coinfection with B. burgdorferi and/or A. phagocytophilum in patients who have severe or persistent symptoms despite appropriate anti-infective treatment for babesiosis.178

Nocturnal Recumbency Leg Muscle Cramps

Not approved by FDA for the treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps†.180 182 185 187 Should not be used in the management of this or related conditions (e.g. restless legs syndrome†).180 182 185 187 201

Although quinine has been used in the past for the prevention and treatment of nocturnal recumbency leg muscle cramps† (night cramps),175 176 177 182 184 185 198 there are no adequate and well-controlled studies evaluating efficacy and safety for this use.119 120 121 122 124 154 155 184 185

Quinine has a narrow margin of safety and may cause unpredictable serious and life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions, QT interval prolongation, serious cardiac arrhythmias (including torsades de pointes), serious hematologic reactions (including thrombocytopenia and HUS/TTP), and other serious adverse events (e.g., blindness, deafness) requiring medical intervention and hospitalization.180 184 185 187 188 191 193 201 Fatalities associated with use of the drug have been reported.180 185 187 201 (See Cautions.) The known risks associated with the use of quinine, in the absence of evidence of safety and efficacy of the drug for the treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps†, outweigh any potential benefits for this benign, self-limiting condition.180 184 185 187

FDA has determined that quinine preparations (including preparations containing any quinine salt alone or in fixed combination with vitamin E) are not generally recognized as safe and effective for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg muscle cramps.185 Promotion of quinine for self-medication of nocturnal leg cramps has been prohibited in the US since February 1995 because of safety concerns.154 155 184 185 In addition, FDA ordered that marketing of all unapproved quinine preparations be discontinued as of December 11, 2006.182 (See Preparations.)

quiNINE Dosage and Administration

Administration

Quinine is administered orally as quinine sulfate.180 183 186

Although quinine has been administered by slow IV infusion as quinine dihydrochloride, a parenteral preparation of the drug no longer available for use in the US, either commercially or from CDC.148 149 When parenteral antimalarial therapy indicated, use IV quinidine gluconate.148 149 143 144

Oral Administration

Take with food to minimize possible GI irritation.134 180 183 186

Dosage

Available as quinine sulfate; dosage expressed in terms of the salt.180 183 186

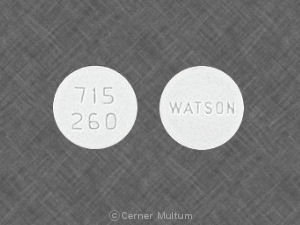

The only FDA-approved preparations of quinine currently commercially available in US are capsules containing 324 mg of quinine sulfate (Qualaquin, generic);180 183 186 the drug was previously available in US as capsules containing 325 mg.185 This difference in quinine preparations may result in minor disparities between some published dosage recommendations that were based on the previously available 325-mg capsules and dosage recommendations for the currently available 324-mg capsules.a

Pediatric Patients

Malaria

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria Caused by Chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or Unidentified Plasmodial Species

OralChildren ≥8 years of age†: 10 mg/kg 3 times daily for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).134 Use in conjunction with a 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin.134 144

Children <8 years of age†: If quinine regimen used, CDC states quinine monotherapy may be given for 7 days or quinine can be given in conjunction with clindamycin for the usually recommended duration.143 In rare circumstances, a regimen of quinine and doxycycline or tetracycline can be considered.143 (See Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria under Uses.)

Do not exceed usual adult dosage.143 144

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria Caused by Chloroquine-resistant P. vivax†

OralChildren ≥8 years of age†: 10 mg/kg 3 times daily for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).134 Do not exceed usual adult dosage.143 144

Use in conjunction with 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline or tetracycline.134 144 A 14-day regimen of primaquine also indicated to provide a radical cure and prevent delayed attacks or relapse of P. vivax malaria.134 143 144

Treatment of Severe Malaria†

Oral10 mg/kg 3 times daily to complete 7 or 3 days of total IV quinidine and oral quinine therapy as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).199 Do not exceed usual adult dosage.143

IV quinidine gluconate must be used initially; after ≥24 hours and after parasitemia reduced to <1% and oral therapy tolerated, oral quinine may be substituted.144

Use quinidine/quinine regimen in conjunction with 7-day regimen of doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin (administered IV or orally as tolerated).144

Presumptive Self-treatment of Malaria†

Oral10 mg/kg 3 times daily for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere) given in conjunction with a 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline.134

Not included in current CDC recommendations for presumptive self-treatment of malaria in travelers.115

Babesiosis†

Oral

IDSA recommends 8 mg/kg (up to 650 mg) every 8 hours in conjunction with clindamycin (7–10 mg/kg [up to 600 mg] IV or orally every 6–8 hours) given for 7–10 days.178

Other clinicians recommend 30 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses given for 7–10 days in conjunction with oral clindamycin (20–40 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses for 7–10 days).134

For mild to moderate babesiosis, clinical improvement should be evident within 48 hours after initiation of treatment and symptoms should resolve completely within 3 months.178 Low-grade parasitemia may persist in some patients for months after completion of treatment.178 Regardless of presence or absence of symptoms, IDSA suggests that retreatment be considered if babesial parasites or amplifiable babesial DNA detected in blood ≥3 months after initial treatment.178

Adults

Malaria

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria Caused by Chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum or Unidentified Plasmodial Species

OralManufacturers recommend 648 mg every 8 hours for 7 days for P. falciparum malaria.180 183 186 Manufacturers caution that shorter regimens (3 days) have been used, but data regarding these regimens limited and they may be less effective than a 7-day regimen.180 183 186

CDC and other clinicians recommend 650 mg (two 324-mg capsules) every 8 hours for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).134 144 Use in conjunction with 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin.134 143 144

Pregnant women: CDC recommends 650 mg (two 324-mg capsules) every 8 hours for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).144 Use in conjunction with 7-day regimen of oral clindamycin.143 144 Alternatively, if benefits outweigh risks, used in conjunction with oral doxycycline or tetracycline.144

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria Caused by Chloroquine-resistant P. vivax†

Oral650 mg (two 324-mg capsules) every 8 hours for 7 or 3 days as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).134 144 Use in conjunction with 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline or tetracycline.134 143 A 14-day regimen of primaquine also indicated to provide a radical cure and prevent delayed attacks or relapse of P. vivax malaria.134 143 144

Pregnant women: CDC recommends 650 mg (two 324-mg capsules) every 8 hours for 7 days (regardless of where infection was acquired).144 Used alone143 144 or, if benefits outweigh risks, used in conjunction with oral doxycycline or tetracycline.144 Then, give chloroquine (300 mg [500 mg of chloroquine phosphate] once weekly) as prophylaxis for the duration of the pregnancy until primaquine can be given after delivery to provide a radical cure and prevent relapse.143 144

Treatment of Severe Malaria†

Oral650 mg (two 324-mg capsules) every 8 hours to complete 7 or 3 days of total IV quinidine and oral quinine therapy as determined by geographic origin of infecting parasite (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere).144

IV quinidine gluconate must be used initially; after ≥24 hours and after parasitemia reduced to <1% and oral therapy tolerated, oral quinine may be substituted.144

Use quinidine/quinine regimen in conjunction with 7-day regimen of doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin (administered IV or orally as tolerated).144

Presumptive Self-treatment of Malaria†

Oral650 mg every 8 hours given for 7 or 3 days (7 days if malaria acquired in Southeast Asia or 3 days if acquired elsewhere) in conjunction with a 7-day regimen of oral doxycycline.134

Not included in current CDC recommendations for presumptive self-treatment of malaria in travelers.115

Babesiosis†

Oral

IDSA and other clinicians recommend 650 mg every 6–8 hours in conjunction with clindamycin (300–600 mg IV every 6 hours or 600 mg orally every 8 hours) given for 7–10 days.134 178

For mild to moderate babesiosis, clinical improvement should be evident within 48 hours after initiation of treatment and symptoms should resolve completely within 3 months.178 Low-grade parasitemia may persist in some patients for months after completion of treatment.178 Regardless of presence or absence of symptoms, IDSA suggests that retreatment be considered if babesial parasites or amplifiable babesial DNA detected in blood ≥3 months after initial treatment.178

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Treatment of Uncomplicated or Severe Malaria

Oral

Do not exceed usual adult dosage.143 144

Babesiosis

Oral

Maximum 650 mg per dose.178

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Mild to moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A or B): Dosage adjustment not necessary;180 183 186 monitor closely for adverse effects.180 183 186

Severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C): Do not use.180 183 186 (See Hepatic Impairment under Cautions.)

Renal Impairment

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Severe chronic renal failure: 648-mg loading dose followed 12 hours later by maintenance doses of 324 mg given every 12 hours; dosage based on computer models.180 183 186

Mild or moderate renal impairment: Safety and pharmacokinetics not determined to date.180 183 186

Geriatric Adults

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Dosage adjustment not necessary.180 183 186

Cautions for quiNINE

Contraindications

-

History of potential hypersensitivity reactions associated with previous quinine use, including (but not limited to) thrombocytopenia, TTP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), HUS, or blackwater fever (acute intravascular hemolysis, hemoglobinuria, and hemoglobinemia).180 183 186 (See Hypersensitivity Reactions under Cautions.)

-

Hypersensitivity to mefloquine or quinidine.180 183 186 (See Hypersensitivity Reactions under Cautions.)

-

Prolonged QT interval.180 183 186 (See QT Prolongation and Other Cardiovascular Effects under Cautions.)

-

Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency.180 183 186 (See G-6-PD Deficiency under Cautions.)

-

Myasthenia gravis.180 183 186 (See Myasthenia Gravis under Cautions.)

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

Use for Treatment or Prevention of Nocturnal Leg Cramps†

Quinine has a narrow margin of safety and may cause unpredictable serious and life-threatening hypersensitivity reactions, QT interval prolongation, serious cardiac arrhythmias (including torsades de pointes), serious hematologic reactions (including thrombocytopenia and HUS/TTP), and other serious adverse events (e.g., blindness, deafness) requiring medical intervention and hospitalization.180 183 184 185 186 187 193 201 Fatalities reported.180 183 185 186 201

Quinine not approved by FDA for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps†, and should not be used in the management of this or related conditions (e.g., restless legs syndrome†).180 182 183 185 186 187 201 The known risks associated with use of quinine, in the absence of evidence of safety and efficacy of the drug for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg cramps†, outweigh any potential benefits for this benign, self-limiting condition.180 183 184 185 186 187

FDA has determined that quinine preparations (including preparations containing any quinine salt alone or in fixed combination with vitamin E) are not generally recognized as safe and effective for treatment or prevention of nocturnal leg muscle cramps†.185 Promotion of quinine for self-medication of nocturnal leg cramps† has been prohibited in the US since February 1995 because of safety concerns.154 155 184 185

Because of serious safety concerns, FDA initiated several regulatory actions in December 2006 to remove unapproved quinine preparations from the US market.182 185 187 Despite these efforts, quinine still being prescribed for uses other than malaria, and FDA continues to receive reports of serious adverse effects associated with the drug.187

From April 2005 to October 2008, the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (AERS) received 38 reports of serious adverse events associated with quinine (e.g., hematologic events, cardiovascular events, GI symptoms, hearing loss, rash, electrolyte imbalance, drug interactions).187 201 The majority of these reports (66%) involved patients who used quinine for unlabeled indications (prevention or treatment of leg cramps or restless leg syndrome†),187 201 and most (63%) involved serious or potentially fatal hematologic events.201 (See Hematologic Effects under Cautions.)

Hematologic Effects

Serious, life-threatening, and sometimes fatal hematologic reactions, including thrombocytopenia108 180 183 186 188 201 and HUS/TTP,180 201 have been reported in patients receiving quinine, especially those using the drug for unlabeled indications (prevention or treatment of leg cramps or restless leg syndrome†).187 201 Subsequent development of chronic renal impairment has occurred in patients with quinine-associated TTP.180 183 186 201

In 24 reported cases of serious hematologic reactions, median time to onset was approximately 2 weeks after initiation of quinine.201 Most recovered when the drug was discontinued and other therapeutic interventions initiated, but there were 2 fatalities (one related to TTP and the other related to hemolysis).201

If thrombocytopenia occurs, discontinue quinine since continued therapy puts patient at risk for fatal hemorrhage.180 183 186 Thrombocytopenia usually resolves within 1 week after quinine discontinued.180 Quinine-induced thrombocytopenia is immune-mediated and re-exposure to quinine from any source may result in a more rapid and more severe course of thrombocytopenia compared to original episode.180 183 186

QT Prolongation and Other Cardiovascular Effects

QT interval prolongation has been a consistent finding in studies evaluating ECG changes in individuals receiving oral or parenteral quinine and has occurred independent of age, clinical status, or disease severity.180 183 186 Maximal increases in QT interval correlate with peak plasma quinine concentrations.180 183 186

Concentration-dependent prolongation of PR and QRS intervals also reported in patients receiving oral quinine.180 183 186 Patients with underlying structural heart disease and preexisting conduction system abnormalities, geriatric patients with sick sinus syndrome, patients with atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular response, patients with myocardial ischemia, and patients receiving drugs known to prolong the PR interval (e.g., verapamil) or QRS interval (e.g., flecainide, quinidine) are at particular risk.180 183 186

Potentially fatal cardiac arrhythmias, including torsades de pointes and ventricular fibrillation, reported.180 183 186 At least 1 case of fatal ventricular arrhythmia reported in a geriatric patient with preexisting prolonged QT interval who received IV quinine sulfate for treatment of P. falciparum malaria.180 183 186

Do not use in patients with known prolonged QT interval.180 183 186 Avoid use in patients with clinical conditions known to prolong the QT interval (e.g., uncorrected hypokalemia, bradycardia, certain cardiac conditions).180 183 186

Use caution in patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter.180 183 186 A paradoxical increase in ventricular response rate may occur with quinine, similar to that observed with quinidine.180 183 186 Monitor closely if digoxin used to prevent a rapid ventricular response.180 183 186 (See Digoxin under Interactions.)

Do not use concomitantly with other drugs known to cause QT interval prolongation, including class IA antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide) and class III antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide).180 183 186 (See Drugs That Prolong the QT Interval under Interactions.)

Avoid use with drugs that are CYP3A4 substrates and are known to cause QT prolongation (e.g., cisapride [available in the US only under a limited-use protocol], pimozide, halofantrine [not commercially available in the US], quinidine).180 183 186 (See Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes under Interactions.)

G-6-PD Deficiency

Potential for hemolysis and hemolytic anemia if used in patients with G-6-PD deficiency.180 183 186 Discontinue immediately if evidence of hemolysis occurs.180 183 186

Do not use in patients with G-6-PD deficiency.180 183 186

Myasthenia Gravis

Has neuromuscular blocking activity and may exacerbate muscle weakness if used in patients with myasthenia gravis.180 183 186

Do not use in patients with myasthenia gravis.180 183 186

Sensitivity Reactions

Hypersensitivity Reactions

Serious hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylactic shock, anaphylactoid reactions, urticaria, serious rashes (e.g., Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis), angioedema, facial edema, bronchospasm, and pruritus, reported.180 183 185 186 191

Other serious adverse reactions also reported and may be due to hypersensitivity, including thrombocytopenia, HUS/TTP, ITP, blackwater fever, disseminated intravascular coagulation, leukopenia, neutropenia, granulomatous hepatitis, and acute interstitial nephritis.180 183 185 186 191 194 195 (See Hematologic Effects under Cautions.)

Cross-sensitivity to quinine has been documented in individuals hypersensitive to mefloquine or quinidine.180 183 186

Discontinue quinine if there are signs or symptoms of hypersensitivity (rash, hives, severe itching, severe flushing, trouble breathing).180 183 186

Photosensitivity Reactions

Photosensitivity reported.180 183 186 197

General Precautions

Cinchonism

A cluster of symptoms referred to as “cinchonism” occurs in practically all patients receiving quinine.180 183 186 Most manifestations of cinchonism are reversible and resolve following discontinuance of quinine.180 183 186

Manifestations of mild cinchonism include headache, vasodilation and sweating, nausea, tinnitus, hearing impairment, vertigo or dizziness, blurred vision, and disturbance in color perception.180 183 186 More severe cinchonism manifests as vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, deafness, blindness, and disturbances in cardiac rhythm or conduction.180 183 186

Hypoglycemia

Quinine stimulates release of insulin from the pancreas,180 183 186 and quinine-induced hypoglycemia has been reported.180 183 186 196

Clinically important hypoglycemia may occur, especially in pregnant women.180 183 186

Male Fertility

Decreased sperm motility and increased percentage of sperm with abnormal morphology reported from a study in 5 men receiving quinine (600 mg 3 times daily for 1 week).180 183 186 Testicular toxicity (e.g., atrophy or degeneration of seminiferous tubules, decreased sperm count and motility, decreased testosterone concentrations in serum and testes) reported in animals.180 183 186

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Manufacturers states quinine should be used during pregnancy only if potential benefits justify potential risks to the fetus.180 183 186

CDC recommends quinine and clindamycin as a regimen of choice for treatment of uncomplicated chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria in pregnant women.143 144 (See Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria under Uses.)

Crosses the placenta.180 183 186 Although quinine concentrations may be measurable in the fetus and cord blood of women who received the drug near the time of delivery (see Distribution under Pharmacokinetics), such concentrations may not be therapeutic for the fetus.180 183 186 If congenital malaria suspected, evaluate infant after delivery and treat with antimalarial agents if appropriate.180 183 186

Deafness and optic nerve hypoplasia reported rarely in children exposed in utero when the mother received high-dose quinine therapy during pregnancy.180 183 186

Although published data of >1000 pregnancies exposed to quinine (majority of exposures occurred after first trimester) have not shown an increase in teratogenic effects over background rates in the general population, there are few well-controlled studies to date evaluating the drug in pregnant women.180 183 186

In animal studies evaluating sub-Q or IM quinine, teratogenic or fetotoxic effects (e.g., death in utero, degenerated auditory nerve and spiral ganglion, CNS anomalies, hemorrhage, mitochondrial changes in cochlea) demonstrated in some species.180 183 186

Hypoglycemia, due to increased pancreatic secretion of insulin, has been associated with quinine use, especially in pregnant women.180 183 186

No evidence to date that quinine causes uterine contractions at dosages recommended for the treatment of malaria;180 183 186 doses several fold higher than those used to treat malaria may stimulate the pregnant uterus.180 183 186

Lactation

Distributed into milk.180 183 186

Only limited information available regarding safety of quinine in breast-fed infants.180 183 186 Although quinine generally considered compatible with breast-feeding, assess the risks and benefits to the infant and mother and use with caution in nursing women.180 183 186

Plasma quinine concentrations may not be therapeutic in infants of nursing mothers receiving quinine.180 183 186 If malaria suspected in the infant, provide appropriate evaluation and treatment.180 183 186

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children <16 years of age.180 183 186

Quinine is included in CDC recommendations for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in pediatric patients†.143 144 (See Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria under Uses.) The drug also is used for follow-up after an initial parenteral antimalarial regimen in children with severe malaria†.199 200 (See Treatment of Severe Malaria under Uses.)

Geriatric Use

Clinical studies did not include sufficient numbers of individuals ≥65 years of age to determine whether they respond differently than younger adults.180 183 186 Other reported clinical experience has not identified differences in responses between geriatric adults and younger patients.180 183 186

Closely monitor geriatric patients for adverse effects.180 183 186

Hepatic Impairment

If used in adults with mild to moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A or B), monitor closely for adverse effects associated with quinine.180 183 186

Do not use in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C); oral clearance is decreased, volume of distribution increased, and half-life of the drug prolonged relative to individuals with normal hepatic function.180 183 186

Renal Impairment

Reduced dosage recommended when used for treatment of acute uncomplicated malaria in adults with severe chronic renal failure.180 183 186 (See Renal Impairment under Dosage and Administration.) The effects of mild or moderate renal impairment on safety and pharmacokinetics not determined to date.180 183 186

Common Adverse Effects

Mild cinchonism, manifested as headache, vasodilation and sweating, nausea, tinnitus, hearing impairment, vertigo or dizziness, blurred vision, and disturbance in color perception, occurs in most patients.180 183 186 More severe cinchonism, manifested as vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, deafness, blindness, and disturbances in cardiac rhythm or conduction, also reported.180 183 186

Drug Interactions

Metabolized principally by CYP3A4; may also be metabolized by other CYP enzymes, including 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 2E1.180

Drugs That Prolong the QT Interval

Because quinine prolongs the QT interval, an additive effect on the QT interval might occur if the drug is administered with other drugs that prolong the QT interval.180 183 186 Concomitant use of quinine and other drugs known to cause QT prolongation, including class IA antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., quinidine, procainamide, disopyramide) and class III antiarrhythmic agents (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol, dofetilide), not recommended.180 183 186

Drugs Affecting or Metabolized by Hepatic Microsomal Enzymes

In vivo and in vitro drug interaction studies suggest quinine may inhibit metabolism of drugs that are substrates of CYP3A4 and 2D6.180 183 186

Avoid use with drugs that are CYP3A4 substrates and are known to cause QT prolongation (e.g., cisapride [available in the US only under a limited-use protocol], pimozide, halofantrine [not commercially available in the US], quinidine).180 183 186

Quinine has been shown to decrease metabolism of desipramine in some patients (see Desipramine under Interactions) and may decrease metabolism of some other drugs that are CYP2D6 substrates (e.g., debrisoquine [not commercially available in the US], dextromethorphan, flecainide, methoxyphenamine [not commercially available in the US], metoprolol, paroxetine).180 183 186 If used concomitantly with a CYP2D6 substrate, monitor closely for adverse effects associated with the CYP2D6 substrate.180 183 186

Drugs Affecting or Affected by P-glycoprotein Transport

Quinine is a substrate for and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein,180 183 186 and has the potential to affect transport of drugs that are P-glycoprotein substrates.180 183 186

Specific Drugs and Laboratory Tests

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Antacids (aluminum-and/or magnesium-containing) |

||

|

Antiarrhythmic agents (amiodarone, disopyramide, dofetilide, quinidine, procainamide, sotalol) |

||

|

Anticoagulants (heparin) |

Possible interference with the anticoagulant effects of heparin180 183 186 |

|

|

Anticoagulants (oral) (e.g., warfarin) |

Quinine may potentiate the anticoagulant effects of warfarin and other oral anticoagulants by depressing hepatic synthesis of vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors180 183 186 |

|

|

Anticonvulsants |

Carbamazepine or phenobarbital: Increased peak plasma concentrations and AUC of the anticonvulsant;180 183 186 possible decreased plasma quinine concentrations180 183 186 Phenytoin: No effect on pharmacokinetics of the anticonvulsant;180 183 186 possible decreased plasma quinine concentrations180 183 186 |

Carbamazepine or phenobarbital: If concomitant use with quinine cannot be avoided, frequently monitor serum concentrations of the anticonvulsant and monitor closely for anticonvulsant adverse effects180 183 186 |

|

Cholestyramine |

||

|

Cigarette smoking |

Decreased quinine AUC and peak plasma concentration when used in malaria patients who were heavy smokers;180 183 186 greater effect on quinine pharmacokinetics reported when the drug was given to healthy adults who were heavy smokers180 183 186 Smoking does not appear to influence the therapeutic outcome in malaria patients treated with quinine180 183 186 |

Manufacturer of quinine suggests that reduced clearance of quinine in patients with acute malaria (see Elimination under Pharmacokinetics) may diminish the metabolic induction effect of smoking on quinine pharmacokinetics180 183 186 Manufacturer states that increased quinine dosage not necessary when treating acute malaria in heavy cigarette smokers180 183 186 |

|

Desipramine |

Decreased metabolism of desipramine in patients who are extensive CYP2D6 metabolizers; no effect in patients who are poor CYP2D6 metabolizers180 183 186 |

Monitor closely for adverse effects if quinine used concomitantly with desipramine180 183 186 |

|

Digoxin |

Increased digoxin AUC and decreased biliary clearance of digoxin180 183 186 |

Closely monitor digoxin plasma concentrations; adjust digoxin dosage as necessary180 183 186 |

|

Grapefruit juice |

No evidence of effect on quinine pharmacokinetics 180 183 186 |

|

|

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists (cimetidine, ranitidine) |

Cimetidine: Decreased quinine clearance and prolonged quinine half-life125 126 Ranitidine: No effect on quinine pharmacokinetics180 183 186 |

Cimetidine: Monitor closely for adverse effects associated with quinine;125 126 180 183 186 if a pharmacokinetic interaction suspected, assess patient’s clinical status and adjust quinine dosage as needed or substitute a different histamine H2-receptor antagonist (e.g., ranitidine)125 126 Ranitidine: May be preferred when a histamine H2-receptor antagonist indicated in a patient receiving quinine180 183 186 |

|

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors |

Atorvastatin: Possible increased plasma atorvastatin concentrations and increased risk of myopathy or rhabdomyolysis; rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure secondary to myoglobinuria reported rarely180 183 186 |

Carefully weigh benefits and risks if considering concomitant use of quinine and atorvastatin or other HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors that are CYP3A4 substrates (e.g., simvastatin, lovastatin)180 183 186 If used concomitantly, consider lower starting and maintenance dosages of the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor and monitor closely for signs or symptoms of muscle pain, tenderness, or weakness, especially during initial therapy180 183 186 Discontinue the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor if CPK concentrations are markedly elevated or if myopathy (defined as muscle aches or weakness in conjunction with CPK concentrations >10 times the ULN) diagnosed or suspected180 183 186 |

|

Isoniazid |

No clinically important effect on pharmacokinetics of quinine180 183 186 |

|

|

Ketoconazole |

Increased quinine AUC and decreased quinine clearance180 183 186 |

Quinine dosage adjustment not required; monitor closely for adverse effects associated with quinine180 183 186 |

|

Macrolides |

Possible increased plasma quinine concentrations;180 183 186 although causal relationship not established, fatal torsades de pointes reported in a geriatric patient who was receiving concomitant therapy with quinine, erythromycin, and dopamine180 183 186 |

|

|

Mefloquine |

Potential additive cardiac effects;180 183 186 ECG abnormalities, including QT interval prolongation, may occur; increased risk for torsades de pointes or other serious ventricular arrhythmias180 183 186 |

Do not use concomitantly;134 use sequentially with caution134 Because mefloquine has long serum half-life (up to 4 weeks),147 use caution if initiating quinine for treatment of malaria in patients who were receiving mefloquine for prophylaxis134 If quinine used for initial treatment of severe malaria, do not initiate mefloquine for follow-up treatment until ≥12 hours after last quinine dose145 |

|

Midazolam |

||

|

Neuromuscular blocking agents |

Pancuronium: Potentiated neuromuscular blockade (e.g., respiratory depression, apnea) reported180 183 186 Succinylcholine or tubocurarine (not commercially available in the US): Possibility of potentiated neuromuscular blockade 180 183 186 |

Avoid use of neuromuscular blocking agents in patients receiving quinine180 183 186 |

|

Nevirapine |

Concomitant use decreases AUC, peak plasma concentration, and elimination half-life of quinine and increases AUC and peak plasma concentration of 3-hydroxyquinine, the major metabolite of quinine190 |

Adjustment of quinine dosage may be necessary in patients receiving nevirapine190 |

|

Oral contraceptives |

Quinine pharmacokinetics not affected by concomitant oral contraceptive therapy (progestin alone or estrogen in combination with progestin)180 183 186 |

|

|

Rifampin |

Decreased quinine AUC and plasma concentrations;180 183 186 quinine treatment failure may occur180 183 186 |

|

|

Ritonavir |

Concomitant use increases quinine peak plasma concentration, AUC, and half-life;180 183 186 no clinically important effects on ritonavir pharmacokinetics180 183 186 |

Avoid concomitant use;180 183 186 if used concomitantly, quinine dosage may need to be reduced203 |

|

Tests, urinary corticosteroids or catecholamines |

Quinine causes falsely elevated results when a modification of the Reddy-Jenkins-Thorn procedure is used for urinary 17-hydroxycorticosteroidsa or when the Zimmermann method is used for urinary 17-ketogenic steroids;180 183 186 no effect on modified Porter-Silber methoda 183 186 Quinine interferes with the Sobel and Henry modification of the trihydroxyindole method for determining urinary catecholamines, resulting in falsely increased concentrationsa |

|

|

Tetracyclines |

Closely monitor for adverse effects associated with quinine180 183 186 |

|

|

Theophylline or aminophylline |

Possible decreased plasma theophylline concentrations and reduced effects of theophylline or aminophylline180 183 186 |

Monitor plasma theophylline concentrations frequently180 183 186 Quinine dosage adjustment not needed; closely monitor for quinine adverse effects180 183 186 |

|

Urinary alkalizers |

Agents that increase urinary pH (e.g., acetazolamide, sodium bicarbonate) may increase plasma quinine concentrations 180 183 186 |

quiNINE Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Oral bioavailability is 76–88% in healthy adults.180 183 186 Quinine exposure higher in patients with malaria than in healthy adults,180 183 186 possibly because malaria may cause impaired hepatic function, which results in decreased quinine total body clearance and volume of distribution.106 107

In adults with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, mean AUC and peak plasma concentrations higher and time to peak concentration longer than that reported in healthy adults.180 183 186 Following a single oral dose, mean time to peak serum concentrations is 5.9 hours in adults with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria compared with 2.8 hours in healthy adults.180 183 186

Food

When a single 324-mg dose of oral quinine sulfate capsules was administered with a high-fat meal in healthy adults, the time to peak concentrations was prolonged to approximately 4 hours; however, mean peak plasma concentration and AUC from 0–24 hours were similar to those achieved following oral administration of the drug under fasted conditions.180 183 186

Special Populations

Pharmacokinetics in children 1.5–12 years of age with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria appear to be similar to that observed in adults with uncomplicated malaria.180 183 186 Following a single dose of 10 mg/kg of oral quinine sulfate in healthy children or children 1.5–12 years of age with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria, mean time to peak quinine concentration was longer (4 versus 2 hours) and mean peak plasma concentration was higher (7.5 versus 3.4 mcg/mL) in children with uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria than in healthy children.180 183 186

Following a single 600-mg dose of oral quinine sulfate, mean AUC in healthy geriatric adults 65–78 years of age is approximately 38% higher than in younger adults 20–35 years of age;180 183 186 mean time to peak quinine concentrations and mean peak plasma concentrations are similar in both age groups.180 183 186

Following a single 600-mg dose of oral quinine sulfate in adults with severe chronic renal failure not receiving any form of dialysis (mean serum creatinine 9.6 mg/dL), median AUC and mean peak plasma concentration increased by 195 and 79%, respectively, compared with adults with normal renal function.180 183 186 Effect of mild or moderate renal impairment on pharmacokinetics of quinine sulfate not determined to date.180 183 186

Following a single 600-mg oral dose of quinine sulfate in otherwise healthy adults with moderate hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class B), mean AUC increased 55% compared with healthy adults with normal hepatic function; mean peak plasma concentrations similar in both groups.180 183 186 Quinine absorption prolonged in adults with hepatitis.180 183 186 Pharmacokinetic data not available to date for patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C).180 183 186

Distribution

Extent

Volume of distribution lower in patients with malaria than in healthy individuals or patients convalescing from malaria.106 Volume of distribution decreases with increasing severity of malarial infection.180 183 186

Intra-erythrocytic quinine concentrations are approximately 30–50% of plasma concentrations.180 183 186 Small amounts distributed into bile and saliva.a

Penetrates relatively poorly into CSF in patients with cerebral malaria;180 183 186 CSF quinine concentrations reported to be 2–7% of concurrent plasma concentrations.106 107 180 183 186

Readily crosses the placenta.180 183 186 In a small number of women who delivered live infants 1–6 days after starting quinine therapy, placental cord plasma quinine concentrations were 1–4.6 mg/L (mean: 2.4 mg/L) and mean ratio of cord plasma to maternal plasma quinine concentrations was 0.32.180 Such placental cord concentrations may not result in therapeutic fetal plasma quinine concentrations.180 183 186

Distributed into milk.180 183 186

Plasma Protein Binding

Approximately 69–92% in healthy adults.106 180 183 186

During active malarial infection, protein binding increased to 78–95%, which correlates with increases in α-1-acid glycoprotein that occur during malarial infection.180 183 186 In one study, quinine was approximately 93% bound to plasma proteins in patients with cerebral malaria and approximately 90% bound in patients with uncomplicated malaria or in patients convalescing from the disease.106

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolized almost exclusively via hepatic oxidative (CYP) pathways into 4 primary metabolites (3-hydroxyquinine, 2′-quinone, O-desmethylquinine, and 10,11-dihydroxydihydroquinine) and 6 secondary metabolites resulting from further biotransformation of the primary metabolites.180 183 186

The major metabolite, 3-hydroxyquinine, is less active than parent drug.180 183 186

In vitro studies indicate quinine is metabolized principally by CYP3A4 and may also be metabolized by other CYP enzymes, including 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 2E1.180

Elimination Route

Approximately 20% of a dose excreted unchanged in urine.180 183 186 Reabsorption of quinine is increased when urine is alkaline; rate of renal excretion of the drug is doubled when urine is acidic compared with when urine is alkaline.180

Negligible to minimal amounts removed by hemodialysis or hemofiltration.180 183 186

Half-life

Adults: 8–21 hours in those with malaria and 7–12 hours in those who are healthy or convalescing from the disease.106 107

Children 1–12 years of age: 11–12 hours in those with malaria and 6 hours in those convalescing from the disease.106

Geriatric adults: Mean elimination half-life after single dose is increased to 18.4 hours.180 183 186 At steady-state, mean elimination half-life is 24 hours in geriatric adults compared with 20 hours in younger adults.180 183 186 Although renal clearance of quinine is similar in geriatric and younger adults, geriatric adults excrete a larger proportion of the dose in urine as unchanged drug compared with younger adults.180 183 186

Special Populations

Plasma concentrations are higher and plasma half-life may be prolonged in patients with malaria.106 107

Adults with hepatitis: Elimination half-life and apparent volume of distribution are increased, but weight-adjusted clearance not altered.180 183 186

Otherwise healthy individuals with mild hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class A): Quinine pharmacokinetics and exposure to 3-hydroxyquinine are similar to that in healthy individuals with normal hepatic function.180 183 186

Individuals with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh class C): Oral clearance of quinine and formation of 3-hydroxyquinine decreased; volume of distribution and plasma elimination half-life increased.180 183 186

Adults with severe chronic renal failure: Mean plasma half-life prolonged to 26 hours.180 Effects of mild and moderate renal impairment on pharmacokinetics and safety not determined to date.180 183 186

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

20–25°C in tight, light-resistant container.180 183 186 Drug darkens on exposure to light.180 183 186

Actions and Spectrum

-

An alkaloid obtained from the bark of the cinchona tree; the levorotatory isomer of quinidine.185

-

Has several effects on skeletal muscle.a Increases the refractory period of muscle by a direct action on muscle fiber so that the response to tetanic stimulation is diminished;a has a curare-like effect and decreases the excitability of the motor endplate so that responses to repetitive nerve stimulation or acetylcholine are reduced;a and affects the distribution of calcium within muscle fiber.a

-

Has cardiovascular effects similar to those of quinidine.180 183 186

-

Exact mechanism of antimalarial activity not determined.180 183 186 Inhibits nucleic acid synthesis, protein synthesis, and glycolysis in P. falciparum and can bind with hemazoin in parasitized erythrocytes.180 183 186

-

A blood schizonticidal agent active against the asexual erythrocytic forms of P. falciparum,180 183 186 P. malariae,a P. ovale,a and P. vivax.189 Not gametocidal against P. falciparum.180 183 186 Inactive against sporozoites or pre-erythrocytic or exoerythrocytic forms of plasmodia.180 183 186

-

P. falciparum malaria clinically resistant to quinine has been reported in some areas of South America, Southeast Asia, and Bangladesh.180 183 186 Strains of P. falciparum with decreased susceptibility to quinine also can be selected in vivo.180 183 186

-

Cross-resistance has been reported between mefloquine and quinine.145 Although cross-resistance has been demonstrated rarely between quinine and 4-aminoquinoline derivatives, quinine may be active against some strains of P. falciparum resistant to chloroquine.a

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of taking the drug exactly as prescribed.180 183 186 Advise patients not to double the next dose if a dose is missed; if >4 hours has elapsed since the missed dose, patient should not take the missed dose and should take the next dose as previously scheduled.180 183 186

-

Importance of taking with food to minimize possible GI irritation.180 183 186

-

Importance of immediately contacting a clinician if malarial symptoms worsen or do not improve within 2 days of initiating quinine therapy or if fever recurs following completion of antimalarial therapy.180 183 186

-

Importance of immediately contacting a clinician if symptoms of hypersensitivity (e.g., rash, hives, severe itching, severe flushing, facial swelling, difficulty breathing), bleeding (e.g., easy bruising, severe nose bleed, bleeding gums, blood in urine or stool, unusual purple, brown, or red skin spots indicating bleeding under the skin), or heart problems (e.g., chest pain, rapid heartbeat, irregular heart rhythm, weakness, sweating, nervousness) occur.180 183 186

-

Importance of informing clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs, as well as any concomitant illnesses.180 183 186

-

Importance of women informing clinicians if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.180 183 186

-

Importance of advising patients of other important precautionary information.180 183 186 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Capsules |

324 mg |

Qualaquin |

AR Scientific |

|

Quinine Sulfate Capsules |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions March 5, 2014. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

21. Katz B, Weetch M, Chopra S. Quinine-induced granulomatous hepatitis. Br Med J. 1983; 286:264-5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1546488/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6402064

100. Morgan MD, Rainford DJ, Pusey CD et al. The treatment of quinine poisoning with charcoal hemoperfusion. Postgrad Med J. 1983; 59:365-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2417512/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6634542

101. White NJ, Warrell DA, Chanthavanich P et al. Severe hypoglycemia and hyperinsulinemia in falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1983; 309:61-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6343877

102. Wittner M, Rowin KS, Tanowitz HB et al. Successful chemotherapy of transfusion babesiosis. Ann Intern Med. 1982; 96:601-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7200341

103. Anon. Clindamycin and quinine treatment for Babesia microti infection. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1983; 32:65-6,72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6405180

104. Gibbs JL, Trafford A. Quinine amblyopia treated by combined haemodialysis and activated resin haemoperfusion. Lancet. 1985; 1:752-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2858017

105. American Academy of Pediatrics. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

106. White NJ. Clinical pharmacokinetics of antimalarial drugs. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1985; 10:187-215. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3893840

107. Report of a WHO Scientific Group. Advances in malaria chemotherapy. Technical Report Series No 711. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1984:21-33,60-85,97-8.

108. Freiman JP. Fatal quinine-induced thrombocytopenia. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 112:308-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2297210

112. Phillips RE, Warrell DA, White NJ et al. Intravenous quinidine for the treatment of severe falciparum malaria. N Engl J Med. 1985; 312:1273-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3887162

113. Boland ME, Roper SMB. Complications of quinine poisoning. Lancet. 1985 date>; 1:384-5.

114. Henry J. Quinine for night cramps. BMJ. 1985; 291:3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1416175/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3926053

115. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC health information for international travel, 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services. Updates may be available at CDC website. http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/yellowbook-home-2014.htm

116. Looareesuwan S, White NJ, Karbwang J et al. Quinine and severe falciparum malaria in late pregnancy. Lancet. 1985; 2:4-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2861481

117. Chow AW. Pharmacokinetics and safety of antimicrobial agents during pregnancy. Rev Infect Dis. 1985; 7:287-313. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3895351

119. Food and Drug Administration. Establishment of a monograph for OTC internal analgesic, antipyretic and antirheumatic products. Docket No. 77N–0094 Fed Regist. 1977; 42:35345-621.

120. Food and Drug Administration. Quinine for the treatment of nocturnal leg muscle cramps for over-the-counter human use; establishment of a monograph; and reopening of administrative record. Docket No. 77N–0094 Fed Regist. 1982; 47:43562-4.

121. Food and Drug Administration. Internal analgesic, antipyretic, and antirheumatic drug products for over-the-counter human use; tentative final monograph for drug products for the treatment and/or prevention of nocturnal leg muscle cramps. Docket No. 77N–0094 Fed Regist. 1985; 50:46588-94. (IDIS 206847)

122. Anon. Quinine for “night cramps” Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1986; 28:110.

123. Dyson EH, Proudfoot AT, Prescott LF et al. Death and blindness to overdose of quinine. BMJ. 1985; 291:31-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1416204/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3926054

124. Warburton A, Royston JP, O’Neil CJ et al. A quinine a day keeps the leg cramps away? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1987; 23:459-65.

125. Wanwimolruk S, Sunbhanich M, Pongmarutai M et al. Effects of cimetidine and ranitidine on the pharmacokinetics of quinine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1986; 22:346-50. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1401143/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3768247

126. Mangini RJ, ed. Drug interaction facts. St. Louis: JB Lipincott Co; 1987(Apr):479a.

127. Ellenhorn MJ, Barceloux DG. Medical toxicology: diagnosis and treatment of human poisoning. New York: Elsevier; 1988:390-5.

128. Kriegman AG (Ciba-Geigy, Summit, NJ): Personal communication; 1987 Oct 20.

129. Centers for Disease Control. Intravenous quinidine gluconate in the treatment of severe Plasmodium falciparum infections. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1985; 34:371-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3923321

130. Agosti JM, Miller KD, Pappaioanou M et al. Plasmodium falciparum malaria and intravenous quinidine gluconate. Ann Intern Med. 1985; 103:307. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3893261

131. Centers for Disease Control. Notice of claimed investigational exemption for a new drug (Quinidine Gluconate Injection USP). FD Form 1571. Atlanta, GA; 1985.

132. Rudnitsky G, Miller KD, Padua T et al. Continuous-infusion quinidine gluconate for treating children with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J Infect Dis. 1987; 155:1040-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3549916

133. Jaeger A, Saunder P, Kopferschmitt J et al. Clinical features and management of poisoning due to antimalarial drugs. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1987; 2:242-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3306266

134. Anon. Drugs for parasitic infections. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2010; 8:e1-16. http://www.medletter.com

135. Okitolonda W, Delacollette C, Malengreau M et al. High incidence of hypoglycaemia in African patients treated with intravenous quinine for severe malaria. BMJ. 1987; 295:716-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1247739/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3117315

136. Punukollu RC, Kumar S, Mullen KD. Quinine hepatotoxicity: an underrecognized or rare phenomenon? Arch Intern Med. 1990; 150:1112-3.

139. Krogstad DJ, Herwaldt BL. Antimalarial agents: specific treatment regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:957-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172324/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3056248

140. Herwaldt BL, Krogstad DJ. Antimalarial agents: specific chemoprophylaxis regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988; 32:953-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC172323/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3056247

141. Krogstad DJ. Chemoprophylaxis and treatment of malaria. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:1538-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3185677

143. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC treatment guidelines: Treatment of malaria (guidelines for clinicians). 2013 Jul. From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Sep 27. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria

144. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for treatment of malaria in the United States (based on drugs currently available for use in the United States–updated July 1, 2013). From the CDC website. Accessed 2013 Sep 27. http://www.cdc.gov/malaria

145. Teva Pharmaceuticals. Mefloquine hydrochloride tablets prescribing information. Sellersville, Pa; 2013 Jun.

147. Karbwang J. Clinical pharmacokinetics of mefloquine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990; 19:264-79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2208897

148. Anon. Treatment of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria with quinidine gluconate: discontinuation of parenteral quinine from CDC drug service. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991; 40:240. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1848916

149. . Treatment with quinidine gluconate of persons with severe Plasmodium falciparum infection: discontinuation of parenteral quinine from CDC Drug Service. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1991; 40:21-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1850497

150. Miller KD, Greenberg AE. Treatment of severe malaria in the United States with a continuous infusion of quinidine gluconate and exchange transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1989; 321:65-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2659994

152. Wyler DJ. Malaria: overview and update. Clin Infect Dis. 1993; 16:449-58. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8513046

154. Food and Drug Administration. Drug products for the treatment and/or prevention of nocturnal leg muscle cramps for over-the-counter human use—final rule (Docket No. 77N-0094). Fed Regist. 1994; 59(161):43234-52.

155. Wolfe SM. Letter to the US Food and Drug Administration regarding the over-the-counter use of quinine sulfate. Washington, DC: Public Citizen’s Health Research Group; 1994 Sept 8.

156. Macguire RB, Stroncek DF. Recurrent pancytopenia, coagulopathy, and renal failure associated with multiple quinine-dependent antibodies. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 119:215-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8323089

157. Schmitt SK. Quinine-induced pancytopenia and coagulopathy. Ann Intern Med. 1994; 120:90-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8250466

158. Spearing RL, Hickton CM, Sizeland P et al. Quinine-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. Lancet. 1990; 336:1535-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1979368

159. Janssen Pharmaceutica. Hismanal (astemizole) tablets prescribing information. Titusville, NJ; 1998 Feb.

160. Janssen Pharmaceutica, Titusville, NJ: Personal communication.

161. Hoechst Marion Roussel, Kansas City, MO: Personal communication.

162. Klausner MA. Dear healthcare provider letter regarding new information concerning drug interaction of astemizole with quinine. Titusville, NJ; 1996 Mar 25.

163. Marion Merrell Dow. Seldane (terfenadine) 60-mg tablets prescribing information. In: Physicians’ desk reference. 50th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1996:1536-8.

166. Lobel HO. Update on prevention of malaria for travelers. JAMA. 1997; 278:1767-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9388154

168. Wolfe MS. Protection of travelers. Clin Infect Dis. 1997; 25:177-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9332506

170. White NJ. The treatment of malaria. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:800-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8703186

173. Krogstad DJ. Plasmodium species (malaria). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 5th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2000:2817-31.

174. Glynne P, Salama A, Chaudhry A et al. Quinine-induced immune thrombocytopenic purpura followed by hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999; 33:133-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9915279

175. Man-Son-Hing M, Wells G, Lau A. Quinine for nocturnal leg cramps: a meta-analysis including unpublished data. J Gen Intern Med. 1998; 13:600-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1497008/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9754515

176. Diener HC, Dethlefsen U, Dethlefsen-Gruber S et al. Effectiveness of quinine in treating muscle cramps: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Int J Clin Pract. 2002; 56:243-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12074203

177. Kanaan N, Sawaya R. Nocturnal leg cramps. Clinically mysterious and painful—but manageable. Geriatrics. 2001; 56:34,39-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11417373

178. Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43:1089-134. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17029130

179. Food and Drug Administration. List of orphan designations and approvals. From FDA web site. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/opdlisting/oopd/index.cfm

180. AR Scientific, Inc. Qualaquin (quinine sulfate) capsules, USP for oral use prescribing information. Philadelphia, PA; 2011 Apr.

181. Krause PJ, Lepore T, Sikand VK et al. Atovaquone and azithromycin for the treatment of babesiosis. N Engl J Med. 2000; 343:1454-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11078770

182. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA advances effort against marketed unapproved drugs: FDA orders unapproved quinine drugs from the market and cautions consumers about “off-label” use of quinine to treat leg cramps. FDA News. Document P06-195. 2006 Dec 11. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2006/ucm108799.htm

183. Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. Quinine sulfate capsules, USP for oral use prescribing information. Morgantown, WV; 2013 Apr.

184. El-Tawil S, Musa TA, El-Tawil T, et al. Quinine for muscle cramps (Protocol). The Cochrane Library. From their web site. Accessed 2/20/2007. http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD005044/frame.html

185. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug products containing quinine; enforcement action dates. [Docket No.2006N-0476] Fed Regist. 2006; 71:75557-60.

186. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA. Quinine sulfate capsules, USP for oral use prescribing information. Sellersville, PA; 2013 Apr.

187. US Food and Drug Administration. Quinine sulfate (marketed as qualoquin) off-label (not approved by FDA) use of quinine. FDA Drug Safety Newsletter. 2009; 2:11-13. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugSafetyNewsletter/ucm167843.htm

188. Brinker AD, Beitz J. Spontaneous reports of thrombocytopenia in association with quinine: clinical attributes and timing related to regulatory action. Am J Hematol. 2002; 70:313-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12210813

189. Chotivanich K, Sattabongkot J, Choi YK et al. Antimalarial drug susceptibility of Plasmodium vivax in the Republic of Korea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009; 80:902-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3444524/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19478246

190. Soyinka JO, Onyeji CO, Omoruyi SI et al. Effects of concurrent administration of nevirapine on the disposition of quinine in healthy volunteers. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2009; 61:439-43. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2752626/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19298689

191. Howard MA, Hibbard AB, Terrell DR et al. Quinine allergy causing acute severe systemic illness: report of 4 patients manifesting multiple hematologic, renal, and hepatic abnormalities. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003; 16:21-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200805/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16278718

192. Everts RJ, Hayhurst MD, Nona BP. Acute pulmonary edema caused by quinine. Pharmacotherapy. 2004; 24:1221-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15460183

193. Prasad RS, Kodali VR, Khuraijam GS et al. Acute confusion and blindness from quinine toxicity. Eur J Emerg Med. 2003; 10:353-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14676522

194. Baliga RS, Wingo CS. Quinine induced HUS-TTP: an unusual presentation. Am J Med Sci. 2003; 326:378-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14671503

195. Knower MT, Bowton DL, Owen J et al. Quinine-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: case report and review of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29:1007-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12682720

196. Limburg PJ, Katz H, Grant CS et al. Quinine-induced hypoglycemia. Ann Intern Med. 1993; 119:218-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8323090

197. Ljunggren B, Hindsén M, Isaksson M. Systemic quinine photosensitivity with photoepicutaneous cross-reactivity to quinidine. Contact Dermatitis. 1992; 26:1-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1600732

198. Fung MC, Holbrook JH. Placebo-controlled trial of quinine therapy for nocturnal leg cramps. West J Med. 1989; 151:42-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1026949/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2669346

199. Praygod G, de Frey A, Eisenhut M. Artemisinin derivatives versus quinine in treating severe malaria in children: a systematic review. Malar J. 2008; 7:210. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2576341/ https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18928535

200. Griffith KS, Lewis LS, Mali S et al. Treatment of malaria in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007; 297:2264-77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17519416

201. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Safety Communication: New risk management plan and patient medication guide for Qualaquin (quinine sulfate). 2010 Jul 8. From FDA website. Accessed 2010 Nov 3. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm218202.htm

202. AR Holding Company, Inc. NDA 21-799: Qualaquin (quinine sulfate) capsules Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). From FDA website. Accessed 2010 Nov 3. http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/rems/index.cfm

203. AbbVie Inc. Norvir (ritonavir) capsules, soft gelatin capsulesfor oral use prescribing information. North Chicago, IL; 2013 Apr.

a. AHFS Drug Information 2009. McEvoy, GK, ed. Quinine sulfate. Bethesda, MD: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2009:882-8.

Related/similar drugs

More about quinine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (20)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: antimalarial quinolines

- Breastfeeding

- En español