Glipizide (Monograph)

Drug class: Sulfonylureas

Introduction

Antidiabetic agent; sulfonylurea.1 2 3

Uses for Glipizide

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Used as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.1 2 3 19 27 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 95

Used as monotherapy and in combination with other antidiabetic agents (e.g., metformin, thiazolidinedione).127 153 156 157 166

Commercially available as a single entity preparation and in fixed combination with metformin.1 95 153

Guidelines from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and other experts generally recommend that use of sulfonylureas for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus be limited or discontinued due to increased risk of weight gain and hypoglycemia.708 709 Sulfonylureas may be considered in patients with access or cost barriers to other antidiabetic regimens.709 When used, these guidelines recommend the lowest possible dosage.708 When selecting a treatment regimen for type 2 diabetes mellitus, consider factors such as cardiovascular and renal comorbidities, drug efficacy and adverse effects, hypoglycemia risk, presence of overweight or obesity, cost, access, and patient preferences.708 709 Weight management should be included as a distinct treatment goal and other healthy lifestyle behaviors should also be considered.708 709

Not indicated for treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus or diabetic ketoacidosis.1 95

Glipizide Dosage and Administration

General

Patient Monitoring

-

Monitor patients carefully to determine the need for continued therapy and to ensure the drug continues to be effective.1 95 In patients usually well controlled by dietary management alone, short-term therapy with glipizide may be sufficient during periods of transient loss of glycemic control.1

-

Monitor therapy with regular clinical and laboratory evaluations, including blood and urine glucose determinations, to determine the minimum effective dosage and to detect primary failure (inadequate lowering of blood glucose concentration at maximum recommended dosage) or secondary failure (loss of control of blood glucose following an initial period of effectiveness).1 HbA1c measurements may also be useful for monitoring patient response.1

Dispensing and Administration Precautions

-

Based on the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), glipiZIDE is a high-alert medication that has a heightened risk of causing significant patient harm when used in error.710

-

The ISMP includes glipiZIDE and glyBURIDE on the ISMP List of Confused Drug Names, and recommends special safeguards to ensure the accuracy of prescriptions for these drugs.711

-

The 2023 American Geriatrics Society (AGS) Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication (PIM) Use in Older Adults includes all sulfonylureas on the list of PIMs that are best avoided by older adults in most circumstances or under specific situations, such as certain diseases, conditions, or care settings.999 The criteria are intended to apply to adults ≥65 years of age in all ambulatory, acute, and institutional settings of care, except hospice and end-of-life care settings.999 The Beers Criteria Expert Panel specifically recommends to avoid sulfonylureas as first- or second-line monotherapy or add-on therapy unless there are substantial barriers to the use of safer and more effective agents; if a sulfonylurea is used, choose short-acting agents (e.g., glipizide) over long-acting agents (e.g., glyburide, glimepiride).999

Administration

Oral Administration

Commercially available as single-entity tablets or in fixed combination with metformin hydrochloride.1 95 153

Immediate-release tablets: Usually administered initially as a single daily dose in the morning before breakfast; recommended to administer 30 minutes before meal to achieve maximum reduction in postprandial blood glucose concentration.1 11 32 Once-daily dosing at dosages up to 15—20 mg shown to provide adequate control of blood glucose throughout the day in most patients with usual meal patterns;1 2 39 40 41 42 43 44 however, some may have a more satisfactory response when administered as 2 or 3 divided doses.1 2 11 44 50 Dosages exceeding 15—20 mg daily should be administered in divided doses before meals of sufficient caloric content.1 2 59 When divided-dosing regimen employed in patients receiving more than 15 mg daily, doses and schedule of administration should be individualized according to patient's meal pattern and response.1 2 11 44 50 51 52 53 57 58 59 60 Dosages greater than 30 mg daily have been given safely in twice-daily dosing regimens for prolonged periods.1 When given concomitantly with colesevelam, administer glipizide at least 4 hours prior to colesevelam.1

Extended-release tablets: Administer once daily, generally with breakfast or first main meal of the day.95 Swallow whole and do not divide, chew, or crush.95 Patients receiving extended-release tablets may occasionally notice a tablet-like substance in their stools; this is normal since tablet containing drug is designed to remain intact and slowly release drug from a nonabsorbable shell during passage through GI tract.95 When given concomitantly with colesevelam, administer glipizide at least 4 hours prior to colesevelam.95

Fixed combination of glipizide and metformin hydrochloride: Should be taken once or twice daily with food.153 See full prescribing information for additional instructions for combination product.153

Dosage

Adults

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Glipizide

OralInitially, 5 mg once daily.1 95

In patients predisposed to hypoglycemia (e.g., debilitated, malnourished, or geriatric patients; those with hepatic or renal impairment; patients taking other antidiabetic drugs), initial dosage of 2.5 mg daily recommended.1 27 71 95

Subsequent dosage should be adjusted according to patient's tolerance and therapeutic response.1 95

Immediate-release tablets: Adjust dosage in increments of 2.5—5 mg at intervals of at least several days.1 2 51 54 59 60 Dosages above 15 mg daily should be divided; total daily dosages above 30 mg have safely been given twice daily.1

Extended-release tablets: Patients receiving immediate-release tablets may be switched to extended-release tablets by giving nearest equivalent total daily dosage once daily.95

Transition period generally not required when transferring from other oral antidiabetic agents to immediate-release tablets.1 Patients being transferred from longer half-life sulfonylureas should be monitored for hypoglycemia during initial 1—2 weeks of transition period due to potential for overlapping drug effect.1

Maintenance dosage of glipizide varies considerably, ranging from 2.5—40 mg daily.1 2 7 27 39 40 41 42 43 44 50 51 52 53 54 56 57 58 59 60 Most patients require 5—25 mg daily as immediate-release tablets27 39 40 41 42 43 44 50 51 52 53 54 56 57 58 59 60 or 5—10 mg daily as extended release tablets, but some clinicians report higher dosages may be necessary.7 25 95 Maximum daily dosage is 40 mg daily as immediate-release tablets or 20 mg daily as extended-release tablets.1 95

Transitioning from Insulin Therapy

Patients maintained on insulin dosages ≤20 units daily: May transfer directly to usual recommended initial dosage of glipizide and administration of insulin may be abruptly discontinued.1 95

Patients requiring insulin dosages >20 units daily: Usual initial recommended dosage of glipizide should be started and insulin dosage reduced by 50%.1 95 Subsequently, insulin is withdrawn gradually and dosage of glipizide is adjusted at intervals of at least several days according to patient's tolerance and therapeutic response.1 95

During period of insulin withdrawal, patients should test urine at least 3 times daily for glucose and ketones, and should be instructed to report results to clinician so that appropriate adjustments can be made, if necessary.94 In some patients, especially those requiring greater than 40 units of insulin daily, manufacturer suggests it may be advisable to consider hospitalization during the transition from insulin to glipizide.1

Glipizide/Metformin Hydrochloride Fixed-combination Therapy

OralInitially, 2.5 mg of glipizide and 250 mg metformin hydrochloride once daily.153 In patients with more severe hyperglycemia (i.e., fasting plasma glucose 280—320 mg/dL), initial dosage of 2.5 mg of glipizide and 500 mg of metformin hydrochloride twice daily may be considered.153 Efficacy not established in patients with fasting plasma glucose concentrations exceeding 320 mg/dL.153

Increase dosage in increments of 1 tablet daily every 2 weeks until minimum effective dosage required to achieve adequate glycemic control or to a maximum daily dosage of 10 mg of glipizide and 2 g of metformin hydrochloride reached.153

Patients inadequately controlled with sulfonylurea or metformin monotherapy: Initially, 2.5 or 5 mg of glipizide and 500 mg of metformin hydrochloride twice daily with morning and evening meals.153 Initial dosage in fixed combination should not exceed daily dosage of glipizide or metformin hydrochloride already being taken to minimize risk of hypoglycemia.153 Dosage of fixed combination should be titrated upwards in increments not exceeding 5 mg of glipizide and 500 mg of metformin hydrochloride until adequate glycemic control or maximum daily dosage of 20 mg of glipizide and 2 g of metformin hydrochloride is reached.153

Patients currently receiving glipizide (or other sulfonylurea agent) and metformin (administered as separate tablets): Initially, 2.5 or 5 mg of glipizide and metformin 500 mg tablets; initial dosage of fixed-combination preparation should not exceed daily dosages of glipizide (or equivalent dosage of other sulfonylurea) and metformin hydrochloride currently being taken.153 When transferring from previous therapy to fixed combination preparation, decision to switch to nearest equivalent dosage or titrate dosage is based on clinical judgment.153 Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia is possible in such patients and change in therapy should be undertaken with appropriate monitoring.153 Safety and efficacy of switching from combined therapy with separate preparations to the fixed-combination preparation have not been established in clinical studies.153

Special Populations

Hepatic Impairment

Glipizide Monotherapy

Immediate release: Initial dosage of 2.5 mg recommended; initial and maintenance dosage should be conservative to avoid hypoglycemic reactions.1

Extended release: Initial dosage of 2.5 mg recommended.95

Glipizide/Metformin Hydrochloride Fixed-combination Therapy

Avoid use in patients with clinical or laboratory evidence of hepatic disease.153

Renal Impairment

Glipizide Monotherapy

Immediate release: No specific population dosage recommendations at this time; initial and maintenance dosage should be conservative to avoid hypoglycemic reactions.1

Extended release: No specific population dosage recommendations at this time.95

Glipizide/Metformin Hydrochloride Fixed-combination Therapy

Do not initiate in patients with eGFR between 30—45 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.153

Contraindicated if eGFR is <30 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.153

If patient already taking and eGFR falls below 45 mL/minute per 1.73 m2, assess benefits and risks of continuing therapy.153 Discontinue if eGFR falls below 30 mL/minute per 1.73 m2.153

Geriatric Patients

Glipizide Monotherapy

Immediate release: Initial starting dosage of 2.5 mg recommended; dosage selection should be conservative, usually starting at low end of dosage range, reflecting greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy, to avoid hypoglycemic reactions.1

Extended release: Initial dosage of 2.5 mg recommended.95

Glipizide/Metformin Hydrochloride Fixed-combination Therapy

No specific population dosage recommendations at this time; do not titrate to maximum dosage to avoid risk of hypoglycemia.153 Initial and maintenance dosage selection should be conservative, usually starting at low end of dosage range, reflecting greater frequency of decreased renal function.153

Cautions for Glipizide

Contraindications

-

Known hypersensitivity to the drug1 95 or any ingredients in the formulation.95

-

Known hypersensitivity to sulfonamide derivatives.95

-

Diabetic ketoacidosis with or without coma.1 Diabetic ketoacidosis should be treated with insulin.1

-

Type 1 diabetes mellitus.1

Warnings/Precautions

Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Mortality

Administration of oral hypoglycemic drugs reported to be associated with increased cardiovascular mortality as compared to treatment with diet alone or diet plus insulin.1 95

Warning based on study conducted by the University Group Diabetes Program (UGDP), which reported that administration of oral antidiabetic agents was associated with increased cardiovascular mortality compared to diet alone or diet and insulin.1 75 95 Results of the UGDP study exhaustively analyzed and there has been general disagreement in scientific and medical communities regarding study's validity and clinical importance.64 72 75 Results from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes (UKPD) study, a large, long-term (over 10 years) study in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes did not confirm increase in cardiovascular events or mortality in group treated intensively with sulfonylureas, insulin, or combination therapy compared with less intensive conventional antidiabetic therapy.96 97 99 100

Although only one drug in the sulfonylurea class (tolbutamide) was included in the UGDP study, it is prudent from a safety standpoint to consider that this warning may also apply to other hypoglycemic drugs in this class, in view of their similarities in mode of action and chemical structure.1 95 Patients should be informed of potential risks and advantages of glipizide and of alternative therapies.1 95

Macrovascular Outcomes

Manufacturer states there are no clinical studies that conclusively establish macrovascular risk reduction with glipizide or any other antidiabetic drug.1 95

Renal and Hepatic Disease

Metabolism and excretion of glipizide may be slowed in patients with renal and/or hepatic impairment.1 If hypoglycemia occurs in such patients, it may be prolonged and appropriate management should be instituted.1

Hypoglycemia

All sulfonylurea drugs are capable of causing severe hypoglycemia.1 95 Hypoglycemia may occur in patients receiving glipizide alone or when used in combination with other antidiabetic agents; concomitant use with other antidiabetic agents increases risk of hypoglycemia.1 2 27 50 54 58 60 70 95 153

Ability to concentrate and react may be impaired as a result of hypoglycemia.95 Severe hypoglycemia can lead to unconsciousness or convulsions and may result in temporary or permanent impairment of brain function or death.95

Early warning signs of hypoglycemia may be different or less pronounced in patients with autonomic neuropathy, in geriatric patients, and in patients taking β-adrenergic blocking agents.95 These situations may result in severe hypoglycemia before the patient is aware of the hypoglycemia.95

Appropriate patient selection and careful attention to dosage are important to avoid glipizide-induced hypoglycemia.1 27 71 95 If hypoglycemia occurs during therapy with the drug, immediate reevaluation and adjustment of glipizide dosage and/or patient's meal pattern are necessary.1 2 27 A lower dosage of glipizide may be required to minimize risk of hypoglycemia when used concomitantly with other antidiabetic agents.95 Educate patients to recognize and manage hypoglycemia.95

Loss of Glycemic Control

When a patient stabilized on any antidiabetic regimen is exposed to stress (e.g., fever, trauma, infection, or surgery), loss of glycemic control may occur.1 At times, it may be necessary to discontinue glipizide and administer insulin.1

Effectiveness of any oral hypoglycemic drug in lowering blood glucose to a desirable level decreases in many patients over a period of time, which may be due to progression of severity of disease or diminished responsiveness to the drug.1

Hemolytic Anemia

Patients with glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency who receive sulfonylureas may develop hemolytic anemia.1 95 In patients with G6PD deficiency, a non-sulfonylurea antidiabetic agent should be considered.1

Hemolytic anemia also reported with glipizide during postmarketing experience in patients who did not have known G6PD deficiency.1 95

Gastrointestinal Obstruction

Obstructive symptoms in patients with known strictures reported in association with another drug with a non-dissolvable extended release formulation.95

Avoid use of extended-release glipizide tablets (Glucotrol XL) in patients with preexisting gastrointestinal narrowing (pathologic or iatrogenic).95

Use of Fixed Combinations

When glipizide is used in fixed combination with metformin, the cautions, precautions, and contraindications associated with metformin must be considered in addition to those associated with glipizide.153

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Available data from a small number of published studies and postmarketing experience with extended-release glipizide tablets in pregnancy over decades have not identified any drug-associated risks for major birth defects, miscarriage, or adverse maternal outcomes.95

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus in pregnancy carries risk to the mother and fetus; however, use of glipizide is generally not recommended and should be used only when clearly necessary (i.e., when insulin therapy is infeasible).1 2 65

Neonates born to women with gestational diabetes treated with sulfonylureas during pregnancy may be at increased risk for neonatal intensive care admission and may develop respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, or birth injury; they also may be large for gestational age.95 Prolonged, severe hypoglycemia lasting up to 4—10 days has been reported in some neonates born to women receiving sulfonylureas up to the time of delivery; this effect has been reported more frequently with use of agents having prolonged elimination half-lives.1 95 To minimize risk of neonatal hypoglycemia if glipizide is used during pregnancy, discontinue drug at least 2 weeks before expected delivery date.95 Neonates should be observed for symptoms of hypoglycemia and respiratory distress and managed accordingly.95

Lactation

Unknown whether glipizide is distributed into milk in humans; some sulfonylureas are distributed into human milk.1 No data on effects on milk production.95 Developmental and health benefits of breast-feeding should be considered along with mother's clinical need for glipizide and any potential adverse effects on the breast-fed child from glipizide or underlying maternal condition.95 If used during breast-feeding, infants should be monitored for signs of hypoglycemia (e.g., jitters, cyanosis, apnea, hypothermia, excessive sleepiness, poor feeding, seizures).95 If glipizide is discontinued and dietary management alone is inadequate for controlling blood glucose concentration, administration of insulin should be considered.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established.1 95

Geriatric Use

No overall differences in effectiveness or safety between younger and older patients, but greater sensitivity cannot be ruled out.1 95 Geriatric patients are particularly susceptible to hypoglycemic action of antidiabetic agents; hypoglycemia may be difficult to recognize in these patients.95 In general, dosage selection should be cautious, usually starting at the low end of dosage range, reflecting the greater frequency of decreased hepatic, renal, or cardiac function, and of concomitant disease or other drug therapy.1

Hepatic Impairment

No information regarding effects of hepatic impairment on glipizide disposition.95 As glipizide is highly protein bound and hepatic biotransformation is predominant route of elimination, pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics may be altered in hepatic impairment.95 If hypoglycemia occurs in such patients, it may be prolonged and appropriate management should be instituted.95

Renal Impairment

Pharmacokinetics not evaluated in patients with varying degrees of renal impairment.95 Limited data indicate that glipizide biotransformation products may remain in circulation for a longer time in subjects with renal impairment than seen in normal renal function.95

Common Adverse Effects

Most common adverse effects (>3%): Dizziness, diarrhea, nervousness, tremor, hypoglycemia, flatulence.95

Drug Interactions

Protein-bound Drugs

Because glipizide is highly protein bound, it theoretically could be displaced from binding sites by, or could displace from binding sites, other protein-bound drugs such as oral anticoagulants, hydantoins, salicylate and other NSAIAs, and sulfonamides.1 2 47 72 Protein binding of glipizide is nonionic; consequently, glipizide may be less likely to be displaced from binding sites by, or displace from binding sites, other highly protein-bound drugs whose protein binding is ionic in nature.46

Patients receiving highly protein-bound drugs should be observed for adverse effects when glipizide is initiated or discontinued and vice versa.1

Drugs That May Alter the Hypoglycemic Effect of Sulfonylureas

Several drugs may enhance the hypoglycemic effect of sulfonylurea antidiabetic agents, including glipizide.1 2 72 95 When these drugs are administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, monitor closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control, respectively.1

Several drugs may decrease the hypoglycemic effect of sulfonylurea antidiabetic agents, including glipizide.1 72 95 When these drugs are administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, monitor closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia, respectively.1 95

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

β-adrenergic blocking agents |

May impair glucose tolerance,62 72 increase frequency or severity of hypoglycemia,62 72 delay rate of recovery of blood glucose following drug-induced hypoglycemia,62 72 alter hemodynamic response to hypoglycemia,62 and possibly impair peripheral circulation62 May potentiate or weaken the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 Signs of hypoglycemia may be reduced or absent95 |

Increased frequency of monitoring may be required95 Use of a β1-selective adrenergic blocking agent may be preferred if concomitant therapy is necessary1 95 |

|

Alcohol |

May potentiate or weaken the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Increased frequency of monitoring may be required95 |

|

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Angiotensin II receptor antagonists |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Atypical antipsychotic agents (e.g., clozapine, olanzapine) |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Azole antifungals |

May result in increased plasma concentrations of glipizide and/or hypoglycemia95 Fluconazole: Increases glipizide AUC by 57%95 165 Voriconazole: May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Fluconazole, miconazole: Monitor closely for hypoglycemia1 95 Voriconazole: Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Calcium channel blocking agents |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Chloramphenicol |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively1 2 72 95 |

|

|

Cimetidine |

Substantially increases AUC of glipizide83 May potentiate hypoglycemic effect of glipizide83 |

Monitor closely for signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia; dosage adjustment of glipizide may be necessary83 |

|

Clonidine |

May either potentiate or weaken the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 Signs of hypoglycemia may be reduced or absent95 |

Increased frequency of monitoring may be required95 |

|

Colesevelam |

Reduces AUC and peak plasma concentration of extended-release glipizide tablets by 12 and 13%, respectively, when used concomitantly1 95 |

Administer glipizide at least 4 hours prior to colesevelam1 95 |

|

Corticosteroids |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Coumarins |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Danazol |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Diazoxide |

When glipizide administered to counter hyperglycemic effect of diazoxide in severely hypertensive patients with impairment in renal function, hypoglycemic reactions resulted87 |

Some clinicians recommend not to use these drugs concomitantly87 |

|

Diuretics |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide1 72 95 Thiazide diuretics: May exacerbate diabetes mellitus, resulting in increased requirements of sulfonylurea antidiabetic agents, temporary loss of glycemic control, or secondary failure72 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 72 95 Thiazide diuretics: Use concomitantly with caution72 |

|

Disopyramide |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Estrogens |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Fibric acid derivatives |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Fluoxetine |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Glucagon |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Guanethidine |

Signs of hypoglycemia may be reduced or absent95 |

Increased frequency of monitoring may be required95 |

|

Histamine H2-receptor antagonists |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Hormonal contraceptives |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 72 |

|

|

Isoniazid |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide1 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 |

|

Monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively1 2 72 |

|

|

Niacin |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 72 |

|

|

NSAIAs |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Pentoxifylline |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Phenothiazines |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 72 |

|

|

Phenytoin |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide1 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 |

|

Pramlintide |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Probenecid |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively1 72 95 |

|

|

Progestogens |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Protease inhibitors |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Quinolones |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Reserpine |

May potentiate or weaken the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 Signs of hypoglycemia may be reduced or absent95 |

Increased frequency of monitoring may be required95 |

|

Rifampin |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 72 |

|

|

Salicylates |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effects of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Somatostatin analogs (e.g., octreotide) |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effects of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Somatropin |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

|

Sulfonamide antibiotics |

May enhance the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide95 |

Observe closely for hypoglycemia or loss of glycemic control when administered or discontinued in patients receiving glipizide, respectively1 95 |

|

Sympathomimetic agents (e.g., albuterol, epinephrine, terbutaline) |

May decrease the hypoglycemic effect of glipizide1 |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively1 |

|

Thyroid hormones |

Observe closely for loss of glycemic control or hypoglycemia when administered or discontinued in patients taking glipizide, respectively95 |

Glipizide Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Rapidly and essentially completely absorbed from GI tract.1 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38

Absolute oral bioavailability: 80—100%.30 31

Biphasic peak serum concentrations may occur, suggesting enterohepatic circulation.30 39

Onset

Peak plasma concentration: 1—3 hours (range: 1—6 hours).1 9 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 39

Onset of hypoglycemic action (fasting state): 15—30 minutes, maximal within 1—2 hours.32 33

Duration

Hypoglycemic action may persist for up to 24 hours.1 39 40 41 42 43 44

Food

Peak plasma concentration delayed 20—40 minutes when administered in fasting state compared to nonfasting state.1 32 33

Special Populations

Glipizide concentrations may be increased in renal or hepatic insufficiency.1

Distribution

Extent

Distributed into bile;30 34 37 very small amounts distributed into erythrocytes and saliva.30

Unknown if distributed into human milk.1

Plasma Protein Binding

92—99%;30 34 36 46 principally nonionic.46 47

Elimination

Metabolism

Almost completely metabolized in liver.1 30 34 35 36 37

Elimination Route

Excreted principally in the urine (60—90%) as unchanged drug and metabolites within 24—72 hours.30 34 35 36 37 Less than 10% excreted as unchanged drug.34 36

Also excreted in feces (5—20%),30 34 35 37 almost completely via biliary elimination.30 35 36 37

Half-life

Glipizide: 3—4.7 hours (range: 2—7.3 hours).9 30 31 32 33 34 35 38 39 48

Glipizide metabolites: 2—6 hours.37

Special Populations

Half-life of metabolites prolonged to greater than 20 hours in impaired renal function;37 however, glipizide metabolites largely considered inactive.37 49

Pharmacokinetics and/or pharmacodynamics may be altered in hepatic impairment.95

Renal excretion and terminal elimination half-life of metabolites substantially decreased and increased, respectively, in severe renal impairment.37

No differences in pharmacokinetics observed in geriatric patients compared with younger subjects.95

Stability

Storage

Oral

Tablets

Store at 20—25°C in a tight, light-resistant container.1

Tablets, extended release

Store at 20—25°C (excursions permitted to 15—30°C) protected from moisture and humidity.95

Actions

-

Precise mechanism of hypoglycemic action unknown; appears to lower blood glucose principally by binding to the sulfonylurea receptor in the pancreatic beta cell plasma membrane, leading to closure of ATP-sensitive potassium channels and simulating the release of insulin.1 2 3 5 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 95

-

Also appears to enhance peripheral insulin action7 10 12 at postreceptor (probably intracellular) site(s)16 17 18 during short term therapy.

-

During prolonged administration, extrapancreatic effects appear to substantially contribute to hypoglycemic action;3 5 7 8 10 12 13 14 16 17 23 24 principal effects appear to include enhanced peripheral sensitivity to insulin and reduction of basal hepatic glucose production.3 5 7 8 13 14 16 17 23 24

-

On a weight basis, glipizide is one of the most potent sulfonylurea agents.2 3 5

Advice to Patients

-

Advise patients to read the FDA-approved patient labeling (Patient Information).95

-

Inform patients of the potential risks (including potential adverse effects) and advantages of glipizide and of alternative therapies.1 95

-

When glipizide is used in fixed combination with other drugs, inform patients of other precautionary information about the concomitant agent(s).1 95 153

-

Advise patients that glipizide immediate-release tablets should be taken approximately 30 minutes before a meal.1

-

Advise patients that glipizide extended-release tablets should be taken with breakfast or the first main meal of the day and that the tablets should be taken whole and should not be chewed, crushed, or divided.95 Inform patients taking glipizide extended-release tablets that they may occasionally notice something that looks like a tablet in their stool.95

-

Inform patients that during periods of stress (e.g., fever, trauma, infection, or surgery), a loss of glycemic control may occur.1 Inform patients that at such times, it may be necessary to discontinue glipizide and administer insulin.1

-

Educate patients and responsible family members on how to recognize and manage hypoglycemia.95 Advise patients and responsible family members on the risks of hypoglycemia, symptoms and treatment, and conditions that predispose to its development.95

-

Inform patients of the importance of adherence to dietary instructions, regular physical activity, periodic blood glucose monitoring and glycosylated hemoglobin (hemoglobin A1c; HbA1c) testing, recognition and management of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, and assessment of diabetes mellitus complications.1 95 708 709

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician of existing or contemplated concomitant therapy, including prescription and OTC drugs and dietary or herbal supplements, as well as any concomitant illnesses.1 95

-

Advise patients to inform their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or breast-feed.1 95 Advise women who breast-feed of the need to monitor the breast-fed infant for signs of hypoglycemia (e.g., jitters, cyanosis, hypothermia, excessive sleepiness, poor feeding, seizures).95

-

Inform patients of other important precautionary information.1 95

Additional Information

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. represents that the information provided in the accompanying monograph was formulated with a reasonable standard of care, and in conformity with professional standards in the field. Readers are advised that decisions regarding use of drugs are complex medical decisions requiring the independent, informed decision of an appropriate health care professional, and that the information contained in the monograph is provided for informational purposes only. The manufacturer’s labeling should be consulted for more detailed information. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. does not endorse or recommend the use of any drug. The information contained in the monograph is not a substitute for medical care.

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

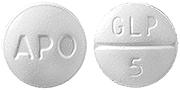

Oral |

Tablets |

5 mg* |

glipiZIDE Tablets |

|

|

10 mg* |

glipiZIDE Tablets |

|||

|

Tablets, extended-release |

2.5 mg* |

glipiZIDE Tablets ER |

||

|

Glucotrol XL |

Pfizer |

|||

|

5 mg* |

glipiZIDE Tablets ER |

|||

|

Glucotrol XL |

Pfizer |

|||

|

10 mg* |

glipiZIDE Tablets ER |

|||

|

Glucotrol XL |

Pfizer |

* available from one or more manufacturer, distributor, and/or repackager by generic (nonproprietary) name

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Oral |

Tablets, film-coated |

2.5 mg with 250 mg Metformin Hydrochloride* |

glipiZIDE with Metformin Hydrochloride Tablets |

|

|

2.5 mg with 500 mg Metformin Hydrochloride* |

glipiZIDE with Metformin Hydrochloride Tablets |

|||

|

5 mg with 500 mg Metformin Hydrochloride* |

glipiZIDE with Metformin Hydrochloride Tablets |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions June 10, 2025. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

References

Only references cited for selected revisions after 1984 are available electronically.

1. Apotex. Glipizide tablets prescribing information. Weston, FL; 2024 Sep.

2. Brogden RN, Heel RC, Pakes GE et al. Glipizide: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1979; 18:329-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/389600

3. Jackson JE, Bressler R. Clinical pharmacology of sulphonylurea hypoglycaemic agents: part 1. Drugs. 1981; 22:211-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7021124

5. Skillman TG, Feldman JM. The pharmacology of sulfonylureas. Am J Med. 1981; 70:361-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6781341

7. Greenfield MS, Doberne L, Rosenthal M et al. Effect of sulfonylurea treatment on in vivo insulin secretion and action in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1982; 31:307-12.

8. Reaven GM. Effect of glipizide treatment on various aspects of glucose, insulin, and lipid metabolism in patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):8-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369970

9. Peterson CM, Sims RV, Jones RL et al. Bioavailability of glipizide and its effect on blood glucose and insulin levels in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1982; 5:497-500. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6765225

10. Lebovitz HE, Feinglos MN. Mechanism of action of the second-generation sulfonylurea glipizide. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):46-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369967

11. Sartor G, Scherstén B, Melander A. Effects of glipizide and food intake on the blood levels of glucose and insulin in diabetic patients. Acta Med Scand. 1978; 203:211-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/345754

12. Feinglos MN, Lebovitz HE. Sulfonylurea treatment of insulin-independent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 1980; 29:488-94. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6990184

13. Lebovitz HE, Feinglos MN, Bucholtz HK et al. Potentiation of insulin action: a probable mechanism for the anti-diabetic action of sulfonylurea drugs. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1977; 45:601-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/903405

14. Kolterman OG, Gray RS, Shapiro G et al. The acute and chronic effects of sulfonylurea therapy in type II diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 1984; 33:346-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6423429

16. DeFronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Koivisto V. New concepts in the pathogenesis and treatment of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983; 74(Suppl. 1A):52-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6337486

17. Lockwood DH, Maloff BL, Nowak SM et al. Extrapancreatic effects of sulfonylureas: potentiation of insulin action through post-binding mechanisms. Am J Med. 1983; 74(Suppl. 1A):102-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6401922

18. Larner J. Mediators of postreceptor action of insulin. Am J Med. 1983; 74(Suppl. 1A):38-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6297300

19. Fineberg SE, Schneider SH. Glipizide versus tolbutamide, an open trial: effects on insulin secretory patterns and glucose concentrations. Diabetologia. 1980; 18:49-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6988265

20. Marco J, Valverde I. Unaltered glucagon secretion after seven days of sulphonylurea administration in normal subjects. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):317-9.

21. Serrano Rios M, Ordonez A, Sanchez MS et al. Long-term effects of glipizide on endocrine pancreas and insulin receptors in type 2 non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetologia. 1983; 25:193-4.

22. Lecomte MJ, Luyckx AS, Lefebvre PF. Plasma glucagon and clinical control of maturity-onset type diabetes: effects of diet, placebo and glipizide. Diabete Metab. 1977; 3:239-43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/340296

23. Best JD, Judzewitsch RG, Pfeifer MA et al. The effect of chronic sulfonylurea therapy on hepatic glucose production in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. Diabetes. 1982; 31:333-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6759249

24. DeFronzo RA, Simonson DC. Oral sulfonylurea agents suppress hepatic glucose production in non-insulin-dependent diabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 1984; 7(Suppl. 1):72-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6428844

25. Greenfield MS, Doberne L, Rosenthal M et al. Lipid metabolism in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: effect of glipizide therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1982; 142:1498-500. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7103631

27. Masbernard A, Giudicelli C, Massey J. Clinical experience with glipizide in the treatment of mostly complicated diabetes. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):356-63.

30. Pentikainen PJ, Neuvonen PJ, Penttila A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of glipizide in healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1983; 21:98-107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6341263

31. Wahlin-Boll E, Almer LO, Melander A. Bioavailability, pharmacokinetics and effects of glipizide in type 2 diabetics. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1982; 7:363-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7116738

32. Wahlin-Boll E, Melander A, Sartor G et al. Influence of food intake on the absorption and effect of glipizide in diabetics and in healthy subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1980; 18:279-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7002565

33. Sartor G, Melander A, Scherstén B et al. Comparative single-dose kinetics and effects of four sulfonylureas in healthy volunteers. Acta Med Scand. 1980; 208:301-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6778079

34. Fuccella LM, Tamassia V, Valzelli G. Metabolism and kinetics of the hypoglycemic agent glipizide in man—comparison with glibenclamide. J Clin Pharmacol. 1973; 13:68-75.

35. Balant L, Fabre J, Zahnd GR. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of glipizide and glibenclamide in man. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1975; 8:63-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/823030

36. Schmidt HAE, Schoog M, Schweer KH et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics as well as metabolism following orally and intravenously administered C14-glipizide, a new antidiabetic. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):320-30.

37. Balant L, Zahnd G, Gorgia A et al. Pharmacokinetics of glipizide in man: influence of renal insufficiency. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):331-8.

38. Huupponen R, Seppala P, Iisalo E. Glipizide pharmacokinetics and response in diabetics. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1982; 20:417-22. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6754633

39. Ostman J, Christenson I, Jansson B et al. The antidiabetic effect and pharmacokinetic properties of glipizide: comparison of a single dose with divided dose regime. Acta Med Scand. 1981; 210:173-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7027750

40. Groop L, Harno K. Diurnal pattern of plasma insulin and blood glucose during glibenclamide and glipizide therapy in elderly diabetics. Acta Endocrinol Suppl. 1980; 239:44-52.

41. Benfield GFA, Pettengell KE, Hunter KR. Once-daily v twice daily glipizide in diabetes mellitus. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 14:614P.

42. Corrall RJM, Thornley P, Bhalla IP et al. Observations on the efficacy and safety of glipizide: a new low dosage sulphonylurea. Acta Ther. 1976; 2:77-88.

43. Azzopardi J, Campbell IW, Clarke BF et al. Duree de l’effet hypoglycemiant utile du glipizide administre une fois par jour a des malades atteints de diabete non insulino-dependant moderement severe. (French; with English abstract.) Acta Ther. 1975; 1:19-29.

44. Almer LO, Johansson E, Melander A et al. Influence of sulfonylureas on the secretion, disposal and effect of insulin. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1982; 22:27-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7047169

46. Crooks MJ, Brown KF. Interaction of glipizide with human serum albumin. Biochem Pharmacol. 1975; 24:298-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/234237

47. Hsu PL, Ma JKH, Luzzi LA. Interactions of sulfonylureas with plasma proteins. J Pharm Sci. 1974; 63:570-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4208196

48. MacWalter RS, El Debani AH, Feely J et al. Studies on glipizide pharmacokinetics and effect in diabetic patients. Br J Clin PHarmacol. 1984; 17:622-3P.

49. Tamassia V. Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of glipizide. Curr Med Res Opin. 1975; 3(Suppl. 1):20-30.

50. Emanueli A, Molari E, Pirola LC et al. Glipizide, a new sulfonylurea in the treatment of diabetes mellitus: summary of clinical experience in 1064 cases. Arzneimittelforschung. 1972; 22:1881-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4267009

51. De Leeuw I, De Baere H, Decraene P et al. An open comparative study of the efficacy and tolerance of a new antidiabetic agent: glipizide. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):364-6.

52. Parodi FA, Caputo G. Long-term treatment of diabetes with glipizide. Curr Med Res Opin. 1975; 3(Suppl. 1):31-6.

53. Bandisode MS, Boshell BR. Clinical evaluation of a new sulfonylurea in maturity onset diabetes—glipizide (K-4024). Horm Metab Res. 1976; 8:88-91.

54. Fowler LK. Glipizide in the treatment of maturity-onset diabetes: a multi-centre, out-patient study. Curr Med Res Opin. 1978; 5:418-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/350493

55. Feinglos MN, Lebovitz HE. Long-term safety and efficacy of glipizide. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):60-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369969

56. Adetuyibi A, Ogundipe OO. A comparative trial of glipizide, glibenclamide and chlorpropamide in the management of maturity-onset diabetes mellitus in Nigerians. Curr Ther Res. 1977; 21:485-90.

57. Blohmé G, Waldenstrom J. Glibenclamide and glipizide in maturity onset diabetes. Acta Med Scand. 1979; 206:263-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/116480

58. Frederiksen PK, Mogensen EF. A clinical comparison between glipizide (Glibenese) and glibenclamide (Daonil) in the treatment of maturity onset diabetes: a controlled double-blind cross-over study. Curr Ther Res. 1982; 32:1-7.

59. Shuman CR. Glipizide: an overview. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):55-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369968

60. Fuchs K. Glipizide versus tolbutamide in maturity-onset diabetes, an open comparative study. Diabetologia. 1973; 9(Suppl.):351-5.

62. Carlisle BA, Kroon LA, Koda-Kimble MA,. Diabetes mellitus. In: Koda-Kimble MA, Young LY, eds. Applied therapeutics: the clinical use of drugs. 8th ed.Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc; 2005: 50-1–50-86.

64. Scientific Advisory Panel of the Executive Committee, American Diabetes Association. Policy statement: the UGDP controversy. Diabetes. 1979; 28:168-70.

65. Asmal AC, Marble A. Oral hypoglycaemic agents: an update. Drugs. 1984; 28:62-78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6378583

66. Lebovitz HE. Clinical utility of oral hypoglycemic agents in the management of patients with noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):94-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6369972

70. Blohmé G, Branegard B, Fahlen M et al. Glipizide-induced severe hypoglycemia. Acta Endocrinol Suppl. 1981; 245:13.

71. Seltzer HS. Severe drug-induced hypoglycemia: a review. Compr Ther. 1979; 5(4):21-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/445986

72. Jackson JE, Bressler R. Clinical pharmacology of sulphonylurea hypoglycaemic agents: part 2. Drugs. 1981; 22:295-320. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7030708

75. Food and Drug Administration. Labeling for oral hypoglycemic drugs of the sulfonylurea class. Docket No. 75N-0062 Fed Regist. 1984; 49:14303-31.

83. Feely J, Peden N. Enhanced sulphonylurea-induced hypoglycaemia with cimetidine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1983; 15:607P.

85. Leslie RDG, Pyke DA. Chlorpropamide-alcohol flushing: a dominantly inherited trait associated with diabetes. Br Med J. 1978; 2:1519-21\. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/728707

87. Farr MJ. Diazoxide, glipizide, hypertension and hypoglycaemia. Lancet. 1976; 2:1138. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/62974

88. Kollind M, Adamson U, Lins PE et al. Influence of glipizide on xylose absorption in type II diabetes. Acta Endocrinol Suppl. 1982; 247:39.

91. Melander A, Wahlin-Boll E. Clinical pharmacology of glipizide. Am J Med. 1983; 75(Suppl. 5B):41-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6424440

94. Bergman M, Felig P. Self-monitoring of blood glucose levels in diabetes: principles and practice. Arch Intern Med. 1984; 144:2029-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6385899

95. Pfizer Inc. Glucotrol XL(glipizide) extended release tablets prescribing information. New York, NY; 2023 Aug.

96. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998; 352:837-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9742976

97. American Diabetes Association. Implications of the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1999; 22(Suppl 1):S27-31.

98. Matthews DR, Cull CA, Stratton RR et al. UKPDS 26: sulphonylurea failure in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients over 6 years. Diabet Med. 1998; 15:297-303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9585394

99. Genuth P. United Kingdom prospective diabetes study results are in. J Fam Pract. 1998; 47:(Suppl 5):S27.

100. Bretzel RG, Voit K, Schatz H et al. The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS): implications for the pharmacotherapy of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1998; 106:369-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9831300

105. Nathan DM. Some answers, more controversy, from UKDS. Lancet. 1998; 352:832-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9742972

112. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. ffect of intensive blood-glucose control with metfromin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet. 1998; 352:854-65. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9742977

113. American Diabetes Association. The United Kingdom Prosepective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) for type 2 diabetes: what you need to know about the results of a long-term study. Washington, DC; September 15, 1998. From American Diabetes Association web site. http://www.diabetes.org

115. Watkins PJ. UKPDS: a message of hope and a need for change. Diabet Med. 1998; 15:895-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9827842

116. Turner RC, Cull CA, Frighi V et al. Glycemic control with diet, sulfonlyurea, metformin, or insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: progressive requirements for multiple therapies (UKPDS 49). JAMA. 1999; 281:2005-12. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10359389

127. Chow CC, Sorensen JP, Tsang LWW et al. Comparison of insulin with or without continuation of oral hypoglycemic agents in the treatment of secondary failure in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1995; 18:307-14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7555472

130. Raskin P. Combination therapy in NIDDM N Engl J Med. 1992; 327:1453-4. Editorial.

131. Landstedt-Hallin L, Bolinder J, Adamson U et al. Comparison of bedtime NPH or preprandial regular insulin combined with glibenclamide in secondary sulfonylurea failure. Diabetes Care. 1995; 18:1183-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7587856

132. Buse J. Combining insulin and oral agents. Am J Med. 2000; 108(Suppl 6A):23S-32S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10764847

133. Trischitta V, Italia S, Mazzarino S et al. Comparison of combined therapies in treatment of secondary failure to glyburide. Diabetes Care. 1992; 15:539-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1499473

134. Johnson JL, Wolf SL, Kabadi UM. Efficacy of insulin and sulfonylurea combination therapy in type II diabetes: a meta-analysis of the randomized placebo-controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1996; 156:259-64. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8572835

135. Florence JA, Yeager BF. Treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am Fam Physician. 1999; 59:2835-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10348076

136. Yki-Jarvinen H, Dressler A, Ziemen M et al. Less nocturnal hypoglycemia and better post-dinner glucose control with bedtime insulin glargine compared with bedtime HPH insulin during insulin combination therapy in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2000; 23:1130-6 (IDIS 451244)

137. Bastyr EJ, Johnson ME, Trautman ME et al. Insulin lispro in the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus after oral agent failure. Clin Ther. 1999; 21:1703-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10566566

138. DeFronzo RA. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1999; 131:281-303. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10454950

139. Pugh JA, Ramirez G, Wagner ML et al. Is combination sulfonylurea and insulin therapy useful in NIDDM patients? A metaanalysis. Diabetes Care. 1992; 15:953-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1387073

140. Krentz AJ, Ferner RE, Bailey CJ. Comparative tolerability profiles of oral antidiabetic agents. Drug Safety. 1994; 11:223-41. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7848543

153. Zydus Pharmaceuticals USA Inc. Glipizide and metformin hydrochloride tablets prescribing information. Pennington, NJ; 2024 Dec.

156. Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. Effect of intensive therapy on the microvascular complications of type 1 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2002; 287:2563-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12020338

157. Wolffenbuttel BHR, Gomist R, Squatrito S et al. Addition of low-dose rosiglitazone to sulphonylurea therapy improves glycaemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabet Med. 2000; 17:40-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10691158

158. Kipnes MS, Krosnick a, Rendell MS et al. Pioglitazone hydrochloride in combination with sulfonylurea therapy improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2001; 111:10-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11448655

159. Chiasson J, Josse R, Hunt J et al. The efficacy of acarbose in the treatment of patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1994; 121:929-935.

160. Coniff RF, Shapiro JA, Seaton TB et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled trial comparing acarbose (BAY g 5421) with placebo, tolbutamide, and tolbutamide-plus-acarbose in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 1995; 98:443-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7733122

161. Calle-Pascual AL, Garcia-Honduvilla J, Martin-Alvarez PJ et al. Comparison between acarbose, metformin, and insulin treatment in type 2 diabetic patients with secondary failure to sulfonylurea treatment. Diabetes Metab. 1995; 21:256-60.

165. Pfizer. Diflucan (fluconazole) tablets and oral suspension prescribing information. New York, NY; 2024 Feb.

166. Hermann LS, Scherstén B, Bitzén PO et al. Therapeutic comparison of metformin and sulfonylurea, alone and in various combinations. Diabetes Care. 1994; 17:1100-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7821128

708. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025; 48(Suppl 1):S181-206.

709. Samson SL, Vellanki P, Blonde L et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinology consensus statement: comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm-2023 update. Endocrin Pract. 2023; 28:305-340.

710. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). ISMP list of high-alert medications in acute care settings (2024). https://www.ismp.org/system/files/resources/2024-01/ISMP_HighAlert_AcuteCare_List_010924_MS5760.pdf (accesssed 2025 Mar 10).

711. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). ISMP list of confused drug names (2024). https://online.ecri.org/hubfs/ISMP/Resources/ISMP_ConfusedDrugNames.pdf (accessed 2025 Mar 10).

999. By the 2023 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023 Jul;71(7):2052-2081. doi: 10.1111/jgs.18372. Epub 2023 May 4. PMID: 37139824

Related/similar drugs

More about glipizide

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Pricing & coupons

- Reviews (76)

- Drug images

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- Patient tips

- During pregnancy

- Support group

- Drug class: sulfonylureas

- Breastfeeding

- En español

Patient resources

Professional resources

Other brands

Glucotrol, Glucotrol XL, GlipiZIDE XL