Clofazimine (Monograph)

Brand name: Lamprene

Drug class: Antileprosy Agents

Introduction

Phenazine dye with antimycobacterial and anti-inflammatory activity.1 2 4 37 70 76 78 117 118 119 139 141

Uses for Clofazimine

Leprosy

Treatment of lepromatous leprosy, including dapsone-resistant lepromatous leprosy and leprosy complicated by erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reactions.1 2 37 86 113 114 115 136 145 146 147 148 149 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218 Used in conjunction with other anti-infectives active against Mycobacterium leprae.1 2 37 86 113 114 115 136 145 146 147 148 149 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218

Treatment of multibacillary leprosy (>5 lesions or skin smear positive for acid-fast bacteria) in rifampin-based multiple-drug regimens.1 2 37 86 113 114 115 136 145 146 147 148 149 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218 WHO recommends a 12-month multiple-drug regimen that includes rifampin, clofazimine, and dapsone.193 198 199 200 201 218

Treatment of paucibacillary leprosy (1–5 lesions) when dapsone cannot be used.1 2 37 86 113 114 115 136 145 146 147 148 149 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 WHO recommends a 6-month multiple-drug regimen of rifampin and dapsone;193 200 218 if dapsone must be discontinued because of severe adverse effects, WHO recommends that clofazimine be substituted.200

Rifampin-based multiple-drug regimens are recommended for the treatment of all forms of leprosy;193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 multiple-drug regimens may reduce infectiousness of the patient more rapidly and delay or prevent emergence of rifampin-resistant M. leprae.193 200

Alternative for treatment and prevention of erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL) reactions (lepra type 2 reactions) in leprosy patients.1 2 37 40 41 69 71 81 82 84 86 93 147 148 149 154 155 156 157 158 164 193 195 196 198 Not as effective or as rapidly acting as other agents used in the treatment of ENL (e.g., corticosteroids, thalidomide);2 37 93 193 203 210 213 do not use alone for treatment of severe ENL.193 203

Has been used for treatment of reversal (type 1) reactions† [off-label] in patients with borderline or tuberculoid leprosy.2 37 71 81 93 Efficacy not fully evaluated;37 81 196 may aggravate the reactional state in some patients.81

Not effective in the treatment of other leprosy-associated inflammatory reactions1 (e.g., Lucio’s phenomenon, downgrading reactions).37 129 130

Not commercially available in the US, but may be obtained for treatment of leprosy from the National Hansen’s Disease Program (NHDP) of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).214 215 216 In rare circumstances, also may be made available from NHDP for other uses.214 215 (See Restricted Distribution under Dosage and Administration.)

Treatment of leprosy and management of leprosy reactional states is complicated and should be undertaken in consultation with a specialist familiar with the disease.215 216 219 For information, consult NHDP by phone at 225-578-9861 or 800-642-2477, by fax at 225-578-9856, or on the Internet at .215 216 219

Mycobacterium Avium Complex (MAC) Infections

Has been used in multiple-drug regimens for treatment of pulmonary and localized extrapulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) infections† [off-label], but safety and efficacy not established.28 43 44 45 46 48 49 50 92 95 152 167 ATS and IDSA state the role of clofazimine in the treatment of MAC lung disease is not established.183

Should not be used for treatment of disseminated MAC infections† [off-label], including infections that have failed to respond to or are resistant to other drugs.183 186 There is some evidence clofazimine is ineffective in these infections and may even be associated with reduced survival.179 183 186

Use of clofazimine for the treatment of any disease other than leprosy is discouraged by WHO and the manufacturer since indiscriminate use may promote emergence of resistant strains of M. leprae.214 (See Restricted Distribution under Dosage and Administration.)

Treatment of MAC infections is complicated and should be directed by clinicians familiar with mycobacterial diseases; consultation with a specialist is particularly important when the patient cannot tolerate first-line drugs or when the infection has not responded to prior therapy or is caused by macrolide-resistant MAC.183

Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis (MDRTB)

Has been used in multiple-drug regimens for the treatment of MDRTB† [off-label], but safety and efficacy not established.217 Not included in current CDC, ATS, and IDSA recommendations for treatment of tuberculosis.47

Use of clofazimine for the treatment of any disease other than leprosy is discouraged by WHO and the manufacturer since indiscriminate use may promote emergence of resistant strains of M. leprae.214 (See Restricted Distribution under Dosage and Administration.)

Inflammatory or Pustular Dermatoses

Has been used in a variety of inflammatory or pustular dermatoses† [off-label], but safety and efficacy not established.53 56 59 62 63 65 100 104 107 110 132 133

Use of clofazimine for the treatment of any disease other than leprosy is discouraged by WHO and the manufacturer since indiscriminate use may promote emergence of resistant strains of M. leprae.214 (See Restricted Distribution under Dosage and Administration.)

Clofazimine Dosage and Administration

Administration

Restricted Distribution

Not commercially available in the US, but may be obtained for treatment of leprosy from the National Hansen’s Disease Program (NHDP) of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA).214 215 216 In rare circumstances, may also may be made available from NHDP for other uses.214 215

For treatment of leprosy, clofazimine is distributed under an Investigational New Drug (IND) application held by NHDP and is available at no cost after the clinician has registered as an investigator under the IND protocol.214 Clinicians requiring clofazimine for a patient with leprosy should contact the Administrative Officer of the Laboratory Research Branch at NHDP by mail at Skip Berman Drive, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, by phone at 225-578-9861 or 800-642-2477, or by fax at 225-578-9856.214 215 216

If use of clofazimine is considered necessary in situations where there are no other comparable or satisfactory treatments available (e.g., treatment of MDRTB), the drug can be distributed by NHDP under a single-patient treatment IND protocol administered by FDA.214 215 To obtain the drug for any use other than treatment of leprosy, clinicians must first contact the Division of Special Pathogen and Immunologic Drug Products (HFD-590), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research of the FDA by phone at 301-796-1600 to register as an investigator under the single-patient treatment IND protocol.214 215 After FDA approval of the single-patient treatment IND, FDA will request NHDP to distribute clofazimine directly to the prescriber.214 215

Oral Administration

Administer orally.1 To maximize absorption,160 give with a meal.1

Dosage

Pediatric Patients

Leprosy

Multibacillary Leprosy

OralChildren ≤10 years of age†: Appropriately adjust dosage (e.g., clofazimine 50 mg twice weekly plus 100 mg once monthly given in conjunction with rifampin [300 mg once monthly] and dapsone [25 mg daily]).198 Continue multiple-drug regimen for 12 months.198

Children 10–14 years of age: 50 mg once every second day plus 150 mg once monthly given in conjunction with rifampin (450 mg once monthly) and dapsone (50 mg once daily).198 218 Continue multiple-drug regimen for 12 months.198 218

Adolescents ≥15 years of age: 50 mg once daily plus 300 mg once monthly given in conjunction with rifampin (600 mg once monthly) and dapsone (100 mg once daily).36 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218 Continue multiple-drug regimen for 12 months.36 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218

An additional 12 months of therapy may be indicated for patients with a high bacteriologic index who demonstrate no improvement (with evidence of worsening) following completion of the initial 12 months of treatment.200

Adults

Leprosy

Multibacillary Leprosy

Oral50 mg once daily plus 300 mg once monthly given in conjunction with rifampin (600 mg once monthly) and dapsone (100 mg once daily).36 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218 Continue multiple-drug regimen for 12 months.36 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 218

An additional 12 months of therapy may be indicated for patients with a high bacteriologic index who demonstrate no improvement (with evidence of worsening) following completion of the initial 12 months of treatment.200

Paucibacillary Leprosy in Patients Unable to Take Dapsone

Oral50 mg once daily plus 300 mg once monthly given in conjunction with rifampin (600 mg once monthly).193 200 218 Continue multiple-drug regimen for 6 months.193 200 218

Erythema Nodosum Leprosum (ENL) Reactions

OralDosage and duration of clofazimine treatment depend on severity of symptoms.1 2 37 93 94 112 147 154 155 156 157 158 164

100–300 mg daily given in 2 or 3 divided doses for up to 3 months1 156 157 193 196 198 or longer37 146 154 156 157 164 may reduce or eliminate corticosteroid requirements.37 85 93 149 193 Severe, corticosteroid-dependent ENL may require more prolonged treatment (up to 7 months)147 148 149 157 and extended treatment (an additional 9–24 months) may be necessary to prevent recurrence.37 147 157

Although dosages up to 400 mg daily have been used to control ENL in some adults,37 93 136 146 147 148 149 154 155 157 195 manufacturer states dosage >200 mg daily not recommended.1

Reduce clofazimine dosage to lowest effective level (e.g., 100 mg daily) as soon as possible after reactive episode is controlled.1 37 146 147 154 156 157 196

Prescribing Limits

Pediatric Patients

Leprosy

Oral

Dosage >100 mg daily should be given for as short a period as possible and only under close medical supervision.1 (See Cautions.)

Dosage >200 mg daily not recommended.1

Adults

Leprosy

Oral

Dosage >100 mg daily should be given for as short a period as possible and only under close medical supervision.1 (See Cautions.)

Dosage >200 mg daily not recommended.1

Special Populations

No special population dosage recommendation at this time.1

Cautions for Clofazimine

Contraindications

Manufacturer states no known contraindications.1

Warnings/Precautions

Warnings

GI Effects

Severe GI effects (e.g., splenic infarction, bowel obstruction, GI bleeding) reported rarely.1 2 11 14 19 22 37 68 127 Exploratory laparotomies were necessary in some patients; several fatalities reported.1 2 11 14 19 22 37 68 127 Although exact cause unknown, autopsies revealed massive deposits of clofazimine crystals in various tissues (e.g., intestinal mucosa, liver, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes).1 2 14 19 22 37 68 74 127 155

Many patients (40–50%) experience abdominal and epigastric pain,1 2 9 11 14 19 22 66 68 69 71 88 127 147 155 diarrhea,1 2 9 14 19 40 68 73 88 126 147 157 nausea,1 2 9 66 68 145 154 vomiting, 1 2 9 11 40 66 68 69 155 157 and GI intolerance.1

GI effects are dose related and occur most frequently with dosage >100 mg daily.2 40 74 136 155 Dosage >100 mg daily should be used for as short a period as possible and only under close medical supervision.1

Use with caution in patients with GI problems such as abdominal pain and diarrhea.1

If patient complains of colicky or burning abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea, reduce clofazimine dosage and, if necessary, increase interval between doses or discontinue the drug.1

General Precautions

Dermatologic Effects

Pink to brownish-black discoloration of skin occurs in most patients (75–100%) and is evident within 1-4 weeks after initiation of clofazimine.1 2 9 19 37 40 71 74 82 86 123 141 142 145 147 148 149 154 155 156 157 158 Degree of discoloration is dose related37 74 82 146 147 and is most pronounced on exposed body parts19 157 (e.g., hairless facial skin in periorbital and perinasal areas, hairless hypopigmented skin on palms and soles)14 and in areas with leprosy lesions.9 19 37 40 141 145 Gradually disappears within 6-12 months after drug discontinued,1 2 9 19 40 75 142 but traces of color may remain for ≥4 years in some individuals.37 74

Clofazimine is a bright-red dye and skin discoloration apparently occurs because drug crystals distribute to and accumulate in tissues and fluids.1 2 37 66 70 73 74 May be particularly disturbing to light-skinned individuals; may cause substantial compliance problems in certain patients or populations.37 74 142 145 149 196 200 Depression secondary to skin discoloration reported; may have contributed to at least 2 suicides.1 86 Warn patients that skin discoloration, as well as discoloration of the conjunctiva and body fluids, may occur.1 71 (See Ocular Effects under Cautions.) Appropriate counseling (e.g., advantages of clofazimine, reversibility of discoloration) may be sufficient to encourage patients to continue treatment.200

Melanosis, similar to that reported with phenothiazines, also has caused skin discoloration in patients receiving clofazimine.141 142 145 Discoloration is blue-grey or blackish brown to black; resolves gradually following discontinuance of the drug but may persist as circumscribed hyperpigmented areas in some patients.142 During treatment, leprosy nodules may be replaced by scar tissue in the form of shiny, jet black, circular macules.142

Ichthyosis1 2 19 40 66 68 71 74 82 90 147 and dry skin (especially on legs and forearms)1 2 19 37 66 68 71 74 82 147 generally occurs as leprosy resolves.147 May be relieved by applying oil,1 71 petrolatum,71 or an emollient lotion containing 25% urea91 to affected areas. Desquamation may occur.147

Ocular Effects

Reversible, dose-related, red-brown discoloration of the conjunctiva,1 9 17 19 37 71 74 142 145 147 cornea,1 17 19 37 74 and lacrimal fluid1 17 71 74 may occur. Bilateral, linear or branched, brownish lines or streaks in the cornea reported in some patients receiving clofazimine dosages of 100–400 mg daily for ≥2 months;2 21 75 128 these lines slowly disappeared after clofazimine treatment was completed.2 75 128 Discoloration in the macular areas of the eye21 37 74 128 and bluish discoloration of the lens71 also reported rarely.

Discoloration of the conjunctiva and other parts of the eye does not appear to affect visual acuity,2 17 19 71 75 but diminished vision reported rarely.1 9 21

Dryness, burning, itching, irritation, and watering of the eyes also reported.1 9

Discoloration of Body Fluids

Reversible, dose-related, red-brown discoloration of sweat,1 2 19 71 74 sputum,1 2 74 urine,1 2 19 71 74 142 feces,1 2 19 74 nasal secretions,71 semen,71 and breast milk71 142 may occur.

Specific Populations

Pregnancy

Category C.1

Crosses the placenta.1 Deeply pigmented skin reported in infants born to women who received clofazimine during pregnancy;1 20 69 71 142 149 157 discoloration gradually faded over the first year.71 No evidence of teratogenicity in these infants.1 20 69 71 146 147 149 157

Use during pregnancy only if potential benefits justify risk to fetus.1

Lactation

Distributed into human milk.1 Red-brown discoloration of breast milk may occur.71 142 Do not use in nursing women unless clearly indicated.1

Pediatric Use

Safety and efficacy not established in children1 ≤12 years.160

Has been used in pediatric patients;1 included in WHO guidelines for treatment of multibacillary leprosy in children.198 218

Geriatric Use

Insufficient experience in patients ≥65 years of age and older to determine whether geriatric patients respond differently than younger adults.1 Clinical experience has not identified differences in response relative to younger adults.1

Select dosage with caution, usually initiating therapy at the low end of the dosage range, because of age-related decreases in hepatic, renal, and/or cardiac function and concomitant disease and drug therapy.1

Common Adverse Effects

Discoloration of skin, eyes, urine, feces, sputum, sweat, tears; GI effects (abdominal and epigastric pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, GI intolerance); eye irritation, itching, dryness, burning.1

Drug Interactions

Specific Drugs

|

Drug |

Interaction |

Comments |

|---|---|---|

|

Dapsone |

Concomitant use of dapsone and clofazimine does not have a clinically important effect on dapsone pharmacokinetics7 18 83 Some evidence suggests dapsone may decrease or nullify some anti-inflammatory effects of clofazimine and theoretically might adversely affect clofazimine’s efficacy in patients with ENL reactions;54 58 61 102 several borderline leprosy and lepromatous leprosy patients with severe, recurrent ENL reactions reportedly required higher clofazimine dosage to control these reactions when dapsone therapy was given concomitantly than when clofazimine was given alone102 |

Manufacturer states that an interaction between dapsone and clofazimine that adversely affects clofazimine’s anti-inflammatory effects has not been confirmed and advises that treatment with both drugs be continued in patients who develop leprosy-associated inflammatory reactions, including ENL, during concomitant therapy1 |

|

Isoniazid |

Possible increased clofazimine plasma and urine concentrations and decreased clofazimine skin concentrations18 |

|

|

Rifampin |

Although one study indicated that concomitant use of clofazimine in leprosy patients receiving rifampin alone or in conjunction with dapsone may decrease plasma concentrations and AUC of rifampin,8 concomitant use of clofazimine in another study in lepromatous leprosy patients receiving dapsone (100 mg daily) and rifampin (600 mg daily) did not affect rifampin pharmacokinetics7 |

Clofazimine Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Bioavailability

Incompletely absorbed from GI tract following oral administration.1 2 3 6 72 76 77 Extent of absorption exhibits considerable interindividual variation1 2 3 87 and depends on several factors (e.g., particle size, dosage form, dosage, presence of food in GI tract).2 3 6 139 146

When clofazimine capsules are used, 45-70% of dose is absorbed.1 2 139 146 160

Peak serum concentrations usually attained within 4-12 hours when dose is given with food.6

Food

Food increases rate and extent of absorption.6 If administered with food containing fat and protein, AUC increased by 60% and peak serum concentrations increased by 30%.6

Plasma Concentrations

Steady-state serum concentrations average 0.7 and 1 mcg/mL after dosages of 100 mg and 300 mg once daily, respectively.1 2 77 160

Multiple-dose studies indicate steady-state serum concentrations may not be attained until ≥30 days after initiation after clofazimine therapy.6 160

Distribution

Extent

Highly lipophilic.1 2 37 70 78 126 138 139 146 Distributed principally to fatty tissue and cells of the reticuloendothelial system;1 2 37 70 78 126 138 139 146 taken up by macrophages throughout the body.1 2 70 126 127 138

Accumulates in highest concentrations in mesenteric lymph nodes,1 2 70 78 126 adipose tissue,1 2 78 adrenals,1 2 78 liver,1 2 70 73 78 126 lungs,78 gallbladder,1 2 78 bile,1 2 78 and spleen.1 2 22 70 73 78 126 Lower concentrations in skin,1 2 78 126 small intestine,1 2 70 73 126 127 lungs,70 73 78 126 heart,78 kidneys,66 70 78 126 pancreas,78 muscle,1 2 78 omentum,126 and bone.1 2

Does not distribute into brain or CSF.2 70 78 126

Crosses human placenta.1

Distributed into human milk.1

Elimination

Metabolism

Metabolic fate not fully elucidated.2 4 5 37 Appears to be partially metabolized; at least 3 metabolites appear to be eliminated in urine.4 5

Elimination Route

Principally excreted in feces,1 2 3 76 77 78 both as unabsorbed drug and via biliary elimination.1 2 77 78 Following a single oral dose, 35–74% of dose may be excreted unchanged in feces2 3 76 77 over the first 72 hours.3 76

Elimination of unchanged clofazimine and its metabolites in urine is negligible during the first 24 hours.1 76 77 Following multiple oral doses, <1% of daily dose is excreted in urine over a 24-hour period.4 76 77

Small amounts excreted in sputum, sebum, and sweat.1 2 139

Half-life

Following a single oral dose, there is an initial distribution phase followed by a slow elimination phase with a terminal elimination half-life of approximately 8 days.160

Tissue half-life following multiple oral doses is estimated to be ≥70 days.1 2 76 118 160 Remains in body tissues for prolonged periods;1 2 3 4 6 76 126 has been found in skin126 and in mesenteric lymph nodes68 2 and 4 years, respectively, after the drug was discontinued.

Stability

Storage

Oral

Capsules

≤30ºC in airtight container; protect from moisture.1 2

Actions and Spectrum

-

Phenazine dye with antimycobacterial and anti-inflammatory activity.1 2 4 37 70 76 78 117 118 119 139 141 Commercially available as capsules containing micronized clofazimine suspended in an oil-wax base.1

-

Mechanism of action against mycobacteria not fully elucidated.1 2 37 118 120 Appears to exert antimycobacterial effect by binding preferentially to mycobacterial DNA and inhibiting replication and growth.1 2 119 120 121 122 124

-

Exerts anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects in vitro and in vivo.1 2 37 54 58 60 61 66 80 101 102 139 146 Precise mechanisms of these effects not fully elucidated,1 37 60 61 80 but appears to cause dose-dependent inhibition of neutrophil motility54 61 80 101 102 and also inhibits mitogen-induced lymphocyte transformation.54 60 61 80 101 May enhance phagocytic activity of polymorphonuclear cells and macrophages2 99 103 and enhance membrane-associated oxidative metabolism in these cells.58 61

-

Clofazimine’s anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects, in addition to antimycobacterial effects, appear to contribute to efficacy in the treatment and prevention of ENL reactions.2 37 54 58 61 66 80 101 102 139

-

Slowly bactericidal against Mycobacterium leprae in vivo.1 36 37 76 118 119 123 Bactericidal against M. tuberculosis163 and M. marinum98 in vitro, but appears to be only bacteriostatic in vitro against other mycobacteria,2 including M. avium complex (MAC).35

-

M. leprae resistant to clofazimine reported only rarely.24 26 27 87 163 193

-

Cross-resistance between clofazimine and dapsone or rifampin not reported to date.1 2 135 139 163 However, there are rare reports of M. leprae resistant to both clofazimine and dapsone, but susceptible to rifampin.26

Advice to Patients

-

Importance of taking with meals.1

-

Advise patients that clofazimine may cause pink to brownish-black discoloration of skin and also may cause red-brown discoloration of eyes and body fluids (e.g., tears, sweat, sputum, urine, feces).1 Counsel patients that such discoloration is reversible, but may take several months or years to disappear after treatment is finished; advise them of the importance of continuing treatment.1

-

Importance of immediately informing clinician if abdominal symptoms (colicky or burning pain in the abdomen, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) occur.1

-

Importance of taking only as prescribed; do not increase dosage or duration of therapy unless otherwise instructed by a clinician.1

-

Advise patients that if skin dryness and ichthyosis occur, these effects may be relieved by applying oil to the skin.1

-

Importance of women informing their clinician if they are or plan to become pregnant or plan to breast-feed.1

-

Importance of informing patients of other important precautionary information.1 (See Cautions.)

Preparations

Excipients in commercially available drug preparations may have clinically important effects in some individuals; consult specific product labeling for details.

Please refer to the ASHP Drug Shortages Resource Center for information on shortages of one or more of these preparations.

Clofazimine is no longer commercially available in the US.214 215 216 However, the drug may be obtained for treatment of leprosy by contacting the National Hansen’s Disease Program (NHDP) of the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) at 225-578-9861 or 800-642-2477.214 215 216 In rare circumstances, the drug also may be made available from NHDP for other uses by contacting the FDA Division of Special Pathogen and Immunologic Drug Products (HFD-590), Center for Drug Evaluation and Research at 301-796-1600.214 215 (See Restricted Distribution under Dosage and Administration.)

|

Routes |

Dosage Forms |

Strengths |

Brand Names |

Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

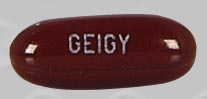

Oral |

Capsules |

50 mg |

Lamprene |

Novartis |

AHFS DI Essentials™. © Copyright 2025, Selected Revisions April 10, 2024. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc., 4500 East-West Highway, Suite 900, Bethesda, Maryland 20814.

† Off-label: Use is not currently included in the labeling approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.

References

1. Novartis. Lamprene (clofazimine) prescribing information. East Hanover, NJ; 2002 Jul.

2. Yawalkar SJ, Vischer W. Lamprene (clofazimine) in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1979; 50:135-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/396428

3. Mathur A, Venkatesan K, Bharadwaj VP et al. Evaluation of effectiveness of clofazimine therapy: monitoring of absorption of clofazimine from gastrointestinal tract. Ind J Lepr. 1985; 57:146-8.

4. Feng PC, Fenselau CC, Jacobson RR. Metabolism of clofazimine in leprosy patients. Drug Metab Dispos. 1981; 9:521-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6120809

5. Feng PC, Fenselau CC, Jacobson RR. A new urinary metabolite of clofazimine in leprosy patients. Drug Metab Dispos. 1982; 10:286-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6125367

6. Schaad-Lanyi Z, Dieterle W, Dubois JP et al. Pharmacokinetics of clofazimine in healthy volunteers. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1987; 55:9-15. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3559339

7. Venkatesan K, Mathur A, Girdhar BK et al. The effect of clofazimine on the pharmacokinetics of rifampicin and dapsone in leprosy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1986; 18:715-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3818497

8. Mehta J, Gandhi IS, Sane SB et al. Effect of clofazimine and dapsone on rifampicin (Lositril) pharmacokinetics in multibacillary and paucibacillary leprosy cases. Ind J Lepr. 1985; 57:297-309.

9. Moore VJ. A review of side-effects experienced by patients taking clofazimine. Lepr Rev. 1983; 54:327-35. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6668986

10. Hassan M, Chaumet S, Brauner M et al. Une cause rar d’atteinte pariétale du grele: L’entéropathie a la clofazimine. Ann Radiol. 1986; 29:549-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3800268

11. Venencie PY, Cortez A, Orieux G et al. Clofazimine enteropathy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986; 15:290-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3745531

12. Belaube P, Devaux J, Pizzi M et al. Small bowel deposition of crystals associated with the use of clofazimine (Lamprene) in the treatment of prurigo nodularis. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1983; 51:328-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6685693

13. Peters JH, Gordon GR, Murray JF. Mutagenic activity of antileprosy drugs and their derivatives. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1983; 51:45-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6683259

14. Bhasin DK, Broor SL, Kaur S et al. Effect of clofazimine: detailed studies of small intestine functions. Ind J Lepr. 1985; 57:364-71.

15. Pavithran K. Exfoliative dermatitis after clofazimine. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1985; 53:645-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2935586

16. Levine S, Saltzman A. Clofazimine enteropathy: possible relation to peyer’s patches. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1986; 54:392-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3489055

17. Negrel AD, Chovet M, Baquillon G et al. Clofazimine and the eye: preliminary communication. Lepr Rev. 1984; 55:349-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6527599

18. Venkatesan K, Bharadwaj VP, Ramu G et al. Study on drug interactions. Lepr Ind. 1980; 52:229-35.

19. Kumar B, Bahadur B, Broor SL et al. Study of toxicity of clofazimine with special reference to structural and functional status of small intestine. Lepr Ind. 1982; 54:246-55.

20. Farb H, West DP, Pedvis-Leftick A. Clofazimine in pregnancy complicated by leprosy. Obstet Gynecol. 1982; 59:122-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7078842

21. Craythorn JM, Swartz M, Creel DJ. Clofazimine-induced bull’s eye retinopathy. Retina. 1986; 6:50-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3704351

22. McDougall AC, Horsfall WR, Hede JE et al. Splenic infarction and tissue accumulation of crystals associated with the use of clofazimine (Lamprene; B663) in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 1980; 102:227-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7387877

23. Kuze F, Kurasawa T, Bando K et al. In vitro and in vivo susceptibility of atypical mycobacteria to various drugs. Rev Infect Dis. 1981; 3:885-97. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7339820

24. Baohong JI. Drug resistance in leprosy—a review. Lepr Rev. 1985; 56:265-78. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3908861

25. Mittal A, Seshadri PS, Conalty ML et al. Rapid, radiometric in vitro assay for the evaluation of the anti-leprosy activity of clofazimine and its analogues. Lepr Rev. 1985; 56:99-108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3894849

26. Kar HK, Bhatia VN, Harikrishnan S. Combined clofazimine- and dapsone-resistant leprosy: a case report. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1986; 54:389-91. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3528345

27. Levy L. Clofazimine-resistant M. leprae. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1986; 54:137-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3519801

28. Horsburgh CR, Mason UG, Farhi DC et al. Disseminated infection with Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare: a report of 13 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). (Baltimore). 1985; 64:36-48.

29. Kiehn TE, Edwards FF, Brannon P et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium avium complex in immunocompromised patients: diagnosis by blood culture and fecal examination, antimicrobial susceptibility tests, and morphological and seroagglutination characteristics. J Clin Microbiol. 1985; 21:168-73. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3972985 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC271607/

30. Wallace RJ, Nash DR, Steele LC. Susceptibility testing of slowly growing mycobacteria by a microdilution MIC method with 7H9 broth. J Clin Microbiol. 1986; 24:976-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3097069 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC269082/

31. Yangco BG, Eikman EA, Solomon DA et al. Rapid radiometric method for determining drug susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981; 19:534-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7247376 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC181472/

32. Gangadharam PR, Candler ER. Activity of some antileprosy compounds against Mycobacterium intracellulare in vitro. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1977; 115:705-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/557943

33. Collins FM, Klayman DL, Morrison NE. Activity of 2-acetylpyridine and 2-acetylquinoline thiosemicarbazones tested in vitro in combination with other antituberculosis drugs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982; 125:58-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6175259

34. Ausina V, Condom MJ, Mirelis B et al. In vitro activity of clofazimine against rapidly growing nonchromogenic mycobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986; 29:951-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3729356 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC284191/

35. Yajko DM, Nassos PS, Hadley WK et al. Therapeutic implications of inhibition versus killing of Mycobacterium avium complex by antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987; 31:117-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3032086 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC174666/

36. Report of a WHO Study Group. Chemotherapy of leprosy for control programmes. Technical Report Series No. 675. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1982:3-33.

37. Hastings HC, ed. Leprosy. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1985:88-99, 193-222.

38. Thirugnanam T, Rajan MA. Borderline reactions treated with clofazimine and corticosteroids. Ind J Lepr. 1985; 57:164-71.

39. Duncan ME, Pearson JM. The association of pregnancy and leprosy—erythema nodosum leprosum in pregnancy and lactation. Lepr Rev. 1984; 55:129-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6748844

40. Burte NP, Chandorkar AG, Muley MP et al. Clofazimine in lepra (ENL) reaction, one year clinical trial. Lepr Ind. 1983; 55:265-77.

41. Saltzman BR, Motyl MR, Friedland GH et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteremia in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. JAMA. 1986; 256:390-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3088290

42. Murray JF, Felton CP, Garay SM et al. Pulmonary complications of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: report of a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. N Engl J Med. 1984; 310:1682-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6328301

43. Furio MM, Wordell CJ. Treatment of infectious complications of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Clin Pharm. 1985; 4:539-54. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2996829

44. Hawkins CC, Gold JW, Whimbey E et al. Mycobacterium avium complex infections in patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1986; 105:184-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3729201

45. National Consensus Conference on Tuberculosis. Disease due to Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare . Chest. 1985; 87(Suppl):139-49S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3967520

46. Tuazon CU, Labriola AM. Management of infectious and immunological complications of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): current and future prospects. Drugs. 1987; 33:66-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3545766

47. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Treatment of tuberculosis, American Thoracic Society, CDC, and Infectious Diseases Society of American. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003; 52(No. RR-11):1-88. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12549898

48. Masur H, Tuazone C, Gill V et al. Effect of combined clofazimine and ansamycin therapy on Mycobacterium avium-Mycobacterium intracellulare bacteremia in patients with AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1987; 155:127-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3794396

49. Greene JB, Sidhu GS, Lewin S et al. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare: a cause of disseminated life-threatening infection in homosexuals and drug abusers. Ann Intern Med. 1982; 97:539-46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6289714

50. Davidson PT, Goble M, Fernandez E et al. Clofazimine (B663) for the treatment of M. intracellulare infections in man. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979; 119(Suppl):398.

51. Jakes JT, Dubois EL, Quismorio FP. Antileprosy drugs and lupus erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 1982; 97:788. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7137755

52. Prendiville J, Cream JJ. Clofazimine-responsive acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1983; 109:90-1.

53. Kelleher D, O’Brien S, Weir DG. Preliminary trial of clofazimine in chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1982; 23:A449-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7035300 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1419600/

54. van Rensburg CE, Gatner EM, Imkamp FM et al. Effects of clofazimine alone or combined with dapsone on neutrophil and lymphocyte functions in normal individuals and patients with lepromatous leprosy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982; 21:693-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7049077 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC181995/

55. Jakes JT, Dubois EL, Quismorio FP. Antileprosy drugs in the treatment of systemic (SLE) and discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). Arthritis Rheum. 1982; 25:S80.

56. Thomsen K, Rothenborg HW. Clofazimine in the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 1979; 115:851-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/453894

57. Crovato F, Levi L. Clofazimine in the treatment of annular lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. 1981; 117:249-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7224651

58. Anderson R. Enchancement by clofazimine and inhibition by dapsone of production of prostaglandin E2 by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985; 27:257-62. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3857019 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC176249/

59. Podmore P, Burrows D. Clofazimine—an effective treatment of Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome or Miescher’s cheilitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1986; 11:173-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3720016

60. Zeis BM, Anderson R. Clofazimine-mediated stimulation of prostaglandin synthesis and free radical production as novel mechanisms of drug-induced immunosuppression. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1986; 8:731-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3465708

61. Anderson R, Lukey P, van Rensburg C et al. Clofazimine-mediated regulation of human polymorphonuclear leukocyte migration by pro-oxidative inactivation of both leukoattractants and cellular migratory responsiveness. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1986; 8:605-19. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3793326

62. Holt PJ, Davies MG, Saunders KC et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinical and laboratory findings in 15 patients with special reference to polyarthritis. Medicine (Baltimore). 1980; 59:114-33. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7360040

63. Chauprapaisilp T, Piamphongsant T. Treatment of pustular psoriasis with clofazimine. Br J Dermatol. 1978; 99:303-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/708598

65. Brandt L, Gartner I, Nilsson PG et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with regional enteritis. Acta Med Scand. 1977; 201:141-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/835365

66. Hastings RC, Jacobson RR, Trautman JR. Long-term clinical toxicity studies with clofazimine (B663) in leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1976; 44:287-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/824210

67. Grabosz JA, Wheate HW. Effect of clofazimine on the urinary excretion of DDS (dapsone). Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1975; 43:61-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1171834

68. Jopling WH. Complications of treatment of clofazimine (Lamprene: B663). Lepr Rev. 1976; 47:1-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1263731

69. Plock H, Leiker DL. A long term trial with clofazimine in reactive lepromatous leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1976; 47:25-34. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1263732

70. Desikan KV, Balakrishnan S. Tissue levels of clofazimine in a case of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1976; 47:107-13. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/948215

71. Karat AB. Long-term follow-up of clofazimine (Lamprene) in the management of reactive phases of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1975; 46(Suppl):105-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1100948

72. Ellard GA. Pharmacological aspects of the chemotherapy of leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1975; 46(Suppl):41-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1165700

73. Desikan KV, Ramanujam K, Ramu G et al. Autopsy findings in a case of lepromatous leprosy treated with clofazimine. Lepr Rev. 1975; 46:181-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1186410

74. Jopling WH. Side-effects of antileprosy drugs in common use. Lepr Rev. 1983; 54:261-70. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6199637

75. Walinder PE, Gip L, Stempa M. Corneal changes in patients treated with clofazimine. Br J Ophthalmol. 1976; 60:526-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/952828 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1017544/

76. Levy L. Pharmacologic studies of clofazimine. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974; 23:1097-109. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4611255

77. Banerjee DK, Ellard GA, Gammon PT et al. Some observations on the pharmacology of clofazimine (B663). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974; 23:1110-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4429180

78. Mansfield RE. Tissue concentrations of clofazimine (B663) in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1974; 23:1116-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4429181

79. Bjune G. Reactions in leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1983; 54(Suppl):661-7S.

80. Anderson R. The immunopharmacology of antileprosy agents. Lepr Rev. 1983; 54:139-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6350776

81. Imkamp FM. Clofazimine (Lamprene or B663) in lepra reactions. Lepr Rev. 1981; 52:135-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7242222

82. Dutta RK. Clofazimine and dapsone: a combination therapy in erythema nodosum leprosum syndrome. Lepr Ind. 1980; 52:252-9.

83. Balakrishnan S, Seshadri PS. Drug interactions: the influence of rifampicin and clofazimine on the urinary excretion of DDS. Lepr Ind. 1981; 53:17-22.

84. Kundu SK, Ghosh S, Hazra S et al. Multiple drug therapy: a comparative study with 2 tier and 3 tier combination of rifampicin, clofazimine, DDS, INAH and thiacetazone in lepromatous cases. Lepr Ind. 1981; 53:248-58.

85. Beeching NJ, Ellis CJ. Leprosy and its chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1982; 10:81-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6749788

86. Browne SG, Harman DJ, Waudby H et al. Clofazimine (Lamprene, B663) in the treatment of lepromatous leprosy in the United Kingdom: a 12 year review of 31 cases, 1966-1978. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1981; 49:167-76. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7196886

87. Warndorff-van Diepen T. Clofazimine-resistant leprosy, a case report. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1982; 50:139-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6749703

88. Lal S, Garg BR, Hameedulla A. Gastro-intestinal side effects of clofazimine. Lepr Ind. 1981; 53:285-8.

89. Duncan ME. Reduced estrogen excretion due to clofazimine? Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1983; 51:112-3. Letter.

90. Aram H. Acquired ichthyosis and related conditions. Int J Dermatol Other Mycobact Dis. 1984; 23:458-61.

91. Caver CV. Clofazimine-induced ichthyosis and its treatment. Cutis. 1982; 29:341-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7083909

92. Polis MA, Tuazon CU. Clues to the early diagnosis of Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985; 109:465-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3838662

93. Jolliffe DS. Leprosy reactional states and their treatment. Br J Dermatol. 1977; 97:345-51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/336075

94. Mason GH, Ellis-Pegler RB, Arthur JF. Clofazimine and eosinophilic enteritis. Lepr Rev. 1977; 48:175-80. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/904424

95. Woods GL, Washington JA. Mycobacteria other than Mycobacterium tuberculosis: review of microbiologic and clinical aspects. Rev Infect Dis. 1987; 9:275-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3296098

96. Revill WDL, Pike MC, Morrow RH et al. A controlled trial of the treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection with clofazimine. Lancet. 1973; 2:873-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4126917

97. Bor S. Clofazimine (Lamprene) in the treatment of vitiligo. S Afr Med J. 1973; 47:1451-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4725625

98. Banerjee DK, Holmes IB. In vitro and in vivo studies of the action of rifampicin, clofazimine and B1912 on Mycobacterium marinum . Chemotherapy. 1976; 22:242-52. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1269290

99. Brandt L, Svensson B. Stimulation of macrophage phagocytosis by clofazimine. Scand J Haematol. 1973; 10:261-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4520014

100. Michaelsson G, Molin L, Ohman S et al. Clofazimine: a new agent for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 1976; 112:344-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1259447

101. Gatner EM, Anderson R, Rensburg CE et al. The in vitro and in vivo effects of clofazimine on the motility of neutrophils and transformation of lymphocytes from normal individuals. Lepr Rev. 1982; 53:85-90. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7098757

102. Imkamp FM, Anderson R, Gatner EM. Possible incompatibility of dapsone with clofazimine in the treatment of patients with erythema nodosum leprosum. Lepr Rev. 1982; 53:148-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7098753

103. Pruzanski W, Saito S. Influence of agents with immunomodulating activity on phagocytosis and bactericidal function of human polymorphonuclear cells. J Rheumatol. 1983; 10:688-93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6417331

104. Berger SA. The use of antimicrobial agents for noninfectious disease. Rev Infect Dis. 1985; 7:357-67. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4023527

105. Pandhi RK, Kanwar AJ, Bedi TR et al. Lupus vulgaris successfully treated with clofazimine. Int J Dermatol. 1978; 17:492-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/681053

106. Shukla SR. Evaluation of clofazimine in vitiligo. Dermatologica. 1981; 163:169-71. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7286357

107. Murray JC. Pyoderma gangrenosum with IgA gammopathy. Cutis. 1983; 32:477-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6360554

108. Jacyk WK. Facial granuloma in a patient treated with clofazimine. Arch Dermatol. 1981; 117:597-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7294854

109. Oluwasanmi JO, Solankee TF, Olurin EO et al. Mycobacterium ulcerans (buruli) skin ulceration in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1976; 25:122-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1259075

110. Rasmussen I. Pyoderma gangrenosum treated with clofazimine: clinical evaluation of 7 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 1983; 63:552-3. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6198851

111. Mackey JP, Barnes J. Clofazimine in the treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Derm. 1974; 91:93-6.

112. Jacobus Pharmaceutical Company Inc. Dapsone tablets USP prescribing information. Princeton, NJ; 1997 Jun.

113. Binford CH, Meyers WM, Walsh GP. Leprosy. JAMA. 1982; 247:2283-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7040711

114. Waters MF. New approaches to chemotherapy for leprosy. Drugs. 1983; 26:465-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6653446

115. Seshadri PS, Ravi NT. Treatment of sulphone resistant leprosy: a review of sixty one cases. Lepr Ind. 1982; 54:639-47.

116. World Health Organization. Basic tests for pharmaceutical substances. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1986:47.

117. Warner AM, Warner VD. Antimycobacterial agents. In: Foye WO, ed. Principles of medicinal chemistry. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1981:750.

118. Alford RH. Antimycobacterial agents. In: Mandell GL, Douglas RG Jr, Bennett JE, eds. Principles and practices of infectious diseases. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1985:261-2.

119. Mandell GL, Sande MA. Antimicrobial agents [continued]: drugs used in the chemotherapy of tuberculosis and leprosy. In: Gilman AG, Goodman LS, Rall TW et al, eds. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 7th ed. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company; 1985;261-2.

120. Morrison NE, Marley GM. The mode of action of clofazimine DNA binding studies. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1976; 44:133-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/945233

121. Morrison NE, Marley GM. Clofazimine binding studies with deoxyribonucleic acid. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1976; 44:475-81. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/798729

122. Morrison NE, Marley GM. Comparative DNA binding studies with clofazimine and B191Z. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1977; 45:188-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/561764

123. Levy L, Shepard CC, Fasal P. Clofazimine therapy of lepromatous leprosy caused by dapsone-resistant Mycobacterium leprae . Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1972; 21:315-21. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4554496

124. David HL, Clavel S, Clement F et al. Effects of antituberculosis and antileprosy drugs on mycobacteriophage D29 growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1980; 18:357-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7447413 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC283997/

125. Damle P, McClatchy JK, Gangadharam PRJ et al. Antimicrobial activity of some potential chemotherapeutic compounds. Tubercle. 1978; 59:135-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/567395

126. Balakrishnan S, Desikan KV, Kamu G. Quantitative estimation of clofazimine in tissues. Lepr Ind. 1976; 48(Suppl):732-8.

127. Harvey RF, Harman RRM, Black C et al. Abdominal pain and malabsorption due to tissue deposition of clofazimine (Lamprene) crystals. Br J Dermatol. 1977; 129:19.

128. Ohman L, Wahlberg I. Ocular side-effects of clofazimine. Lancet. 1975; 2:933-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/53420

129. Wallach D, Cottenot F, Bussel A et al. Plasma exchange therapy in Lucio’s phenomenon. Arch Dermatol. 1980; 116:1101. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7425654

130. Pursley TV, Jacobson RR. Apisarnthanarax P. Lucio’s phenomenon. Arch Dermatol. 1980; 116:201-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7356353

131. Chiodini RJ, Van Kruiningen HJ, Thayer WR et al. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of a Mycobacterium sp. isolated from patients with Crohn’s disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984; 26:930-2. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/6524906 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC180053/

132. Keyzer C, Lilford R, Gordon W et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum, vesicovaginal fistula and endometriosis. S Afr Med J. 1982; 61:843-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7079910

133. Saxe N, Gordon W. Acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome): four case reports. S Afr Med J. 1978; 53:253-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/653521

134. Food and Drug Administration. Cumulative list of orphan drug and biological designations. [Docket No. 84N-0102]. Fed Regist. 1987; 52:3778-81.

135. Food and Drug Administration. Recent drug approvals. FDA Drug Bull. 1987; 17:8-10.

136. Anon. Clofazimine for leprosy and Mycobacterium avium complex infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1987; 29:77-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3614089

138. Barry BC, Conalty ML. The antimycobacterial activity of B 663. Lepr Rev. 1965; 36:3-7. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14241918

139. Vischer WA. The experimental properties of G 30 320 (B 663)—a new anti-leprotic agent. Lepr Rev. 1969; 40:107-110. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5792376

140. Lunn HF, Rees RJ. Treatment of mycobacterial skin ulcers in Uganda with a riminophenazine derivative (B.663). Lancet. 1964; 1:247-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14086214

141. Levy L, Randall HP. A study of skin pigmentation by clofazimine. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1970; 38:404-16. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5534493

142. Browne SG. Red and black pigmentation developing during treatment of leprosy with “B663.” Lepr Rev. 1965; 36:17-20.

143. Shepard CC. Minimal effective dosages in mice of clofazimine (B.663) and of ethionamide against Mycobacterium leprae (34162). Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1969; 132:120-4. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4899207

144. Shepard CC, Walker LL, Van Landingham RM et al. Discontinuous administration of clofazimine (B663) in Mycobacterium leprae infections (35653). Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971; 137:725-7.

145. Browne SG, Hogerzeil LM. “B 663” in the treatment of leprosy: preliminary report of a pilot trial. Lepr Rev. 1962; 33:6-10. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13873759

146. Terencio de las Aguas J. Treatment of leprosy with Lampren (B.663 Geigy). Int J Lepr. 1971; 39:493-503.

147. Schultz EJ. Forty-four months’ experience in the treatment of leprosy with clofazimine (Lamprene (Geigy)). Lepr Rev. 1972; 42:178-87.

148. Karat ABA, Jeevaratnam A, Karat S et al. Double-blind controlled clinical trial of clofazimine in reactive phases of lepromatous leprosy. Br Med J. 1970; 1:198-200. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4904935 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1699291/

149. Waters MFR. Symposium on B.663 (Lampren, Geigy) in the treatment of leprosy and leprosy reaction. Int J Lepr. 1968; 36:560-1.

151. Murray JF, Garay SM, Hopewell PC et al. Pulmonary complications of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: an update. Report of the second National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute workshop. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987; 135:504-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3813212

152. Armstrong D, Gold JWM, Dryjanski J et al. Treatment of infection with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1985; 103:738-43. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2996410

153. Wong B, Edwards FF, Kiehn TE et al. Continuous high-grade Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare bacteremia in patients with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Am J Med. 1985; 78:35-40. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3966486

154. Morgan J. Management of steroid-dependency with clofazimine [Lamprene or B 663 (Geigy)]. Lepr Rev. 1970; 41:229-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5515679

155. Atkinson AJ, Sheagren JN, Barba Rubio J et al. Evaluation of B.663 in human leprosy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1967; 35:119-27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5338956

156. Warren AG. The use of B 663 (clofazimine) in the treatment of Chinese leprosy patients with chronic reaction. Lepr Rev. 1970; 41:74-82. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5453082

157. Imkamp FMJH. A treatment of corticosteroid-dependent lepromatous patients with persistent erythema nodosum leprosum: a clinical evaluation of G.30320 (B663). Lepr Rev. 1968; 39:119-25. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4298736

158. Languillon J. Action de deux nouveaux produits, la thalidomide et le B. 663, sur les formes reactionnelles de la maladie de Hansen. Med Trop (Mars). 1969; 29:497-503. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/5403099

159. Stenger EG, Aeppli L, Peheim E et al. Zur toxikologie des leprostaticums 3-(p-chloranilino)-10-(p-chlorphenyl)-2, 10-dihydro-2-(isopropylimino)-phenazin (G 30320). Arzneimittelforschung. 1970; 20:794-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4989740

160. Gaudino M (Ciba-Geigy Corporation, Summit, NJ): Personal communication; 1987 Oct 23.

161. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations): 1987 Oct.

162. Vischer WA. Antimicrobial activity of the leprostatic drug 3-(p-chloranilino)-10-(p-chlorphenyl)-2, 10-dihydro-2-(isopropylimino)-phenazine (G 30’320, B.663). Arzneimittelforschung. 1970; 20:714-23. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4988610

163. Vischer WA. Antimicrobial activity of the leprostatic drug 3-(p-chloranilino)-10-(p-chlorphenyl)-2, 10-dihydro-2-(isopropylimino)-phenazine (G 30 320). Arzneimittelforschung. 1968; 8:1529-35.

164. Browne SG. B 663 (Geigy): further observations on its suspected anti-inflammatory action. Lepr Rev. 1966; 37:141-5.

165. The United States pharmacopeia, 22nd rev, and the national formulary, 17th ed. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Inc; 1992 (Suppl 6): 2814-5.

167. Anon. Drugs for AIDS and associated infections. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1993; 35:79-86. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8394503

168. Masur H, Public Health Service Task Force on Prophylaxis and Therapy for Mycobacterium Avium Complex. Recommendations on prophylaxis and therapy for disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex disease in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med. 1993; 329:898-904. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8395019

169. CDC. Clinical update: impact of HIV protease inhibitors on the treatment of HIV-infected tuberculosis patients with rifampin. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1996; 45:921-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8927017

170. Flegg PJ, Laing RB, Lee C et al. Disseminated disease due to Mycobacterium avium complex in AIDS. QJM. 1995; 88:617-26. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7583075

171. Chin DP, Reingold AL, Stone EN et al. The impact of Mycobacterium avium complex bacteremia and its treatment on survival of AIDS patients—a prospective study. J Infect Dis. 1994; 170:578-84. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7915749

172. Horsburgh CR Jr, Havlik JA, Ellis DA et al. Survival of patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome and disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex infection with and without antimycobacterial chemotherapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144:557-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/1892294

173. Horsburgh CR Jr. Advances in the prevention and treatment of Mycobacterium avium disease. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:428-30. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8663875

174. Chaisson RE, Benson CA, Dube MP et al. Clarithromycin therapy for bacteremic Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Ann Intern Med. 1994; 121:905-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7978715

176. Sharfran SD, Singer J, Zarowny DP et al. A comparison of two regimens for the treatment of Mycobacterium avium complex bacteremia in AIDS: rifabutin, ethambutol, and clarithromycin versus rifampin, ethambutol, clofazimine, and ciprofloxacin. N Engl J Med. 1996; 335:377-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8676931

177. Benson CA. MAC: pathogenesis and treatment. In: Abstracts of the 3rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Washington, DC, 1996 Jan 28-Feb 1. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1996:166. Abstract.

178. May T, Brel F, Beuscart C et al. A French randomized open trial of 2 clarithromycin combination therapies for MAC bacteremia: first results. Proceedings of ICAAC San Francisco 1995. Abstract No. LB-19.

179. Chaisson RE, Keiser P, Pierce M et al. Controlled trial of clarithromycin/ethambutol with or without clofazimine for Mycobacterium avium complex bacteremia in AIDS. In: Abstracts of the 3rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Washington, DC, 1996 Jan 28-Feb 1. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1996:164. Abstract.

180. Burman W, Reves R, Rietmeijer C et al. Relapse of disseminated mycobacteriun avium complex disease and emergence of resistance to clarithromycin despite treatment with a multidrug regimen. In: Abstracts of the 3rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Washington, DC, 1996 Jan 28-Feb 1. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1996:85. Abstract.

181. Dube M, Sattler F, Torriani F et al. Prevention of relapse of MAC bacteremia in AIDS: a randomized study of clarithromycin plus clofazimine, with or without ethambutol. In: Abstracts of the 3rd Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Washington, DC, 1996 Jan 28-Feb 1. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1996:91. Abstract.

182. Currier J. Progress report: prophylaxis and therapy for MAC. AIDS Clin Care. 1996; 8:45-8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11363599

183. Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 175:367-416. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17277290

186. Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009; 58:1-207; quiz CE1-4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2821196/

187. Wallace RJ Jr, Brown BA, Griffith DE et al. Clarithromycin regimens for pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex: the first 50 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996; 153:1766-72. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8665032

188. Wallace RJ Jr, Griffith DE, Brown BA et al. Clarithromycin treatment for Mycobacterium avium-intercellulare complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996; 153:1990-1. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8665069

189. Reviewers’ comments (personal observations) on the Antituberculosis Agents General Statement 8:16.04.

191. Celgene, Warren, NJ: Personal communication.

192. May T, Brel F, Beuscart C et al. Comparison of combination therapy regimens for treatment of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with disseminated bacteremia due to Mycobacterium avium . Clin Infect Dis. 1997; 25:621-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9314450

193. WHO Expert Committee on Leprosy. Seventh Report. WHO Technical Report Series No. 874. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998:1-43.

194. Whitty CJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy—new perspectives on an old disease. J Infect. 1999; 38:2-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10090496

195. Jacobson RR, Krahenbuhl JL. Leprosy. Lancet. 1999; 353:655-60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10030346

196. MacDougall AC, Ulrich MI. Mycobacterial Disease: Leprosy. In: Fitzpatrick TB, Eisen AZ, Wolff K et al, eds. Dermatology in General Medicine, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw -Hill Inc; 1993:2395-2410.

197. Panda S. Let’s learn some clinical facts on leprosy - before it is eradicated. Bull on Drug Health Information (India). 1998; 5:5-12.

198. Anon. Essential Drugs. WHO Model Formulary. Antibacterials. Antileprosy Drugs. WHO Drug Information. 1997; 11:253-7.

199. WHO Study Group on Chemotherapy of Leprosy. Seventh Report. WHO Technical Report Series No. 847. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994:1-24.

200. WHO. Action programme for the elimination of leprosy (LEP). From WHO Website 1999 Sept 23. http://www.who.int/lep

201. WHO. Reports on individual drugs. Simplified treatment for leprosy. WHO Drug Information. 1997; 11:131.

202. Gelber RH. Leprosy (Hansen’s disease). In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. 4th ed. New York, NY: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:2243-50.

203. Waters MF. An internally-controlled double blind trial of thalidomide in severe erythema nodosum leprosum. Lepr Rev. 1971; 42:26-42. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4338720

205. Sugumaran DS. Leprosy reactions—complications of steroid therapy. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1998; 66:10-5. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9614834

206. Schreuder PAM. The occurrence of reactions and impairments in leprosy: experience in the leprosy control program of three provinces in Northeastern Thailand, 1978–1995. II. Reactions. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1998; 66:159-69. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9728448

207. Partida-Sanchez S, Favila-Castillo L, Pedraza-Sanchez S et al. IgG antibody subclasses, tumor necrosis factor and IFN-γ levels in patients with type II lepra reaction on thalidomide treatment. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998; 116:60-6. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9623511

208. Bhargava P, Mal Kuldeep C, Mathur NK. Erythema nodosum leprosum in subgroups of lepromatous leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1998; 68:373-85.

209. de Carsalade GY, Wallach D, Spindler E et al. Daily multidrug therapy for leprosy; results of a fourteen-year experience. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1997; 65:37-44. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9207752

210. Meyerson MS. Erythema nodosum leprosum. Int J Dermatol. 1996; 35:389-92. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8737869

211. Kifayet A, Shahid F, Lucas S et al. Erythema nodosum leprosum is associated with up-regulation of polyclonal IgG1 antibody synthesis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996; 106:447-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8973611 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2200614/

212. Willcox ML. The impact of multiple drug therapy on leprosy disabilities. Lepr Rev. 1997; 68:350-66. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9503872

213. Lockwood DNJ. The management of erythema nodosum leprosum: current and future options. Lepr Rev. 1996; 67:253-9. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9033196

214. Cunningham S. Dear doctor letter regarding distribution changes for lamprene. East Hanover, NJ; 2005 April 25.

215. Novartis, East Hanover, NJ: Personal communication.

216. National Hansen’s Disease Programs, Baton Rouge, LA: Personal communication.

217. Van Deun A, Salim MA, Das AP et al. Results of a standardised regimen for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Bangladesh. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004. 8:560-7.

218. WHO. Guide to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem. From WHO website Accessed 2009 Mar 23. http://www.who.int/lep

219. National Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy) Program. From the US Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration website. Accessed 2009 Mar 23. http://www.hrsa.gov/hansens/clinicalcenter.htm

Related/similar drugs

More about clofazimine

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: leprostatics

- Breastfeeding