Vitamin D

Scientific Name(s): Cholecalciferol, Ergocalciferol, Vitamin D2, Vitamin D3

Common Name(s): Sunshine vitamin, Vitamin D

Medically reviewed by Drugs.com. Last updated on Nov 21, 2022.

Clinical Overview

Use

Vitamin D supplementation is used for treatment of vitamin D−deficient states in adults and children that can occur due to insufficient dietary sources, insufficient sunshine, increased age, and weight loss surgery. Data also support use in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Use of higher doses has also been suggested to reduce the risk of falls in older populations.

Dosing

Vitamin D3 20 mcg is equivalent to 800 units. Vitamin D3 and D2 are both effective for vitamin D repletion, depending on the dosing regimen; however, D3 is more potent.

Acute respiratory infections (cold, flu, chest infections): In an individual patient data meta-analysis evaluating potential of vitamin D3 supplementation to reduce risk of acute respiratory infections in individuals 0 to 95 years of age, age-appropriate daily or weekly vitamin D3 supplementation without additional bolus doses was suggested to protect against acute respiratory infections, particularly in those with low baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) levels (less than 25 nmol/L).

Elderly: A study conducted to establish the vitamin D requirements in adults 64 years of age and older during the winter determined a recommended dose between 7.9 and 42.8 mcg daily to maintain a serum 25(OH)D level of 25 ng/mL; an evidence-based review recommends 800 to 1,000 units/day of vitamin D to reduce the risk of falls in older populations.

Infants and children: To prevent vitamin D deficiency, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends infants and children receive at least 400 units/day of vitamin D from diet and supplements.

Parkinson disease: Vitamin D3 50,000 units/week plus 600 units/day for 6 months, or 1,200 units/day for 12 months was used in a randomized controlled trial for prevention of vitamin D insufficiency (levels below 30 ng/mL) or deficiency (levels below 20 ng/mL), which can increase disease risk.

Polycystic ovary syndrome: Vitamin D doses ranging from 400 to 12,000 units/day for various durations have been used in randomized controlled trials to increase the number of dominant follicles in patients with PCOS.

Post−weight loss bariatric surgery: A review of guidelines recommends vitamin D3 3,000 units daily until blood levels of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL are attained.

Post−weight loss surgery in patients with vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency: A review of guidelines recommends vitamin D3 3,000 to 6,000 units/day or vitamin D2 50,000 units given 1 to 3 times weekly.

Contraindications

Contraindications have not been identified.

Pregnancy/Lactation

Routine use of supplemental vitamin D during pregnancy is not supported by safety evidence. However, adequate maternal intake of vitamin D−containing foods during lactation ensures that breastfeeding infants receive sufficient vitamin D.

Interactions

The use of statins has been shown to increase serum vitamin D levels. Corticosteroids decrease the metabolism of vitamin D; orlistat reduces vitamin D absorption; and phenobarbital and phenytoin increase hepatic metabolism of vitamin D.

Adverse Reactions

High doses of vitamin D have rarely produced adverse events in clinical trials.

Toxicology

Toxicity due to vitamin D is considered to manifest at serum levels greater than 150 ng/mL of 25(OH)D. Symptoms of hypervitaminosis D include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation, and weakness associated with hypercalcemia.

Related/similar drugs

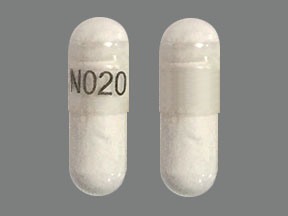

cholecalciferol, ergocalciferol, Vitamin D3, Drisdol, D3-50, Replesta, Ddrops

Source

Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) is synthesized in the skin by transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol exposed to ultraviolet B rays of the sun. Vitamin D binding protein transports D3 to the liver, where it is hydroxylated to the inactive 25(OH)D form (calcidiol). In the kidneys, it is further hydroxylated by the enzyme 1-alpha-hydroxylase to active 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol).(Kulie 2009)

Vitamin D as ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) is found in some plants and in salmon, sardines, mackerel, tuna, cod liver oil, shiitake mushrooms, egg yolk, and fortified foods.(Kulie 2009, NIH 2021, Sage 2010) Deficiency may result from decreased absorption (as in cystic fibrosis or celiac and Crohn diseases, and due to drug interactions), increased catabolism (caused by anticonvulsant and antiretroviral therapy and some immunosuppressant drugs), and hepatic and renal failure, as well as from inadequate intake.(Kulie 2009)

Chemistry

Vitamin D is a hormone precursor and acts to control calcium absorption in the small intestine. It affects parathyroid hormone, which in turn affects the metabolism of skeletal mineralization and calcium homeostasis in the blood. Additionally, effects on cytokines and immune-modulating effects are reported.(Kulie 2009)

The accepted biomarker is 25(OH)D (or calcidiol). Only in advanced renal disease are measurements of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (calcitriol) relevant.(Collins 2009) Concern over standardization of assays exists.(Kulie 2009)

Uses and Pharmacology

Alopecia

Animal data

The role of vitamin D and its receptors in the hair cycle is not well understood, but the potential for topical calcitriol to upregulate the vitamin D receptor has been evaluated in animal models of chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Hair loss was not prevented; however, hair regrowth over the entire animal has been demonstrated.(Amor 2010)

Clinical data

Limited clinical studies have produced varying results regarding the use of vitamin D for chemotherapy-induced alopecia; the ability of topical calcitriol to prevent chemotherapy-induced alopecia is possibly dependent on the chemotherapeutic agents used.(Amor 2010)

Allergies

Clinical data

The World Allergy Organization-McMaster guidelines for the prevention of allergies are based on results of a systematic review and meta-analysis of 29 studies (25 randomized controlled trials) that investigated the effects of vitamin D supplementation versus no supplementation on prevention of allergies. Populations of interest were healthy pregnant women, breastfeeding women, infants, and children up to 9 years of age. Main outcomes focused on asthma or wheezing, allergic rhinitis, any type of eczema, and food allergy. Other outcomes considered were nutritional status, rickets, and adverse events. Overall, the low- to very low–quality of evidence led to imprecise estimates and prevented any recommendations from being made with any certainty. In pregnant women receiving vitamin D for primary prevention of allergy in their children, limited data with overall very low–certainty evidence reflected no effect on the risk of any allergy outcome (including food allergy) or on development of rickets in the children. In contrast, vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy was associated with a lower risk of development of wheezing in children in one cohort study (n=2,478; odds ratio [OR], 0.65; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.93). Vitamin D supplementation in breastfeeding mothers did not appear to affect the risk of asthma and/or wheezing in their children (very low–certainty evidence). Very low–quality data suggested that regular vitamin D supplementation in infants during the first year of life increased the risk of allergic rhinitis (relative risk [RR], 1.31; 95% CI, 1.15 to 1.49) compared with no or irregular vitamin D supplementation. Supplementation in infants had no effect on childhood development of asthma/wheezing. No studies evaluating primary prevention of allergic disease in children were found.(Yepes-Nuñez 2018)

The European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Global Allergy and Asthma European Network, European Dermatology Forum, and World Allergy Organization updated guideline for the definition, classification, diagnosis and management of urticaria (2018) indicated that based on clinical experience, vitamin D is very rarely used in certain contexts as an alternative treatment option for urticaria.(Zuberbier 2018)

Aromatase inhibitor–associated musculoskeletal symptoms

Clinical data

In a phase 3, single-site, randomized, double-blind trial in postmenopausal women with breast cancer (stages I to II) and receiving aromatase inhibitor therapy (N=116), no difference was found in musculoskeletal symptom scores, pain, stiffness, physical function, steady-state concentrations of anastrozole or letrozole, reproductive hormones, or adverse events in the group assigned to a "usual care" group (calcium carbonate 1,000 mg/day plus vitamin D3 dose of 600 units) compared with those assigned to a "high-dose" group (calcium carbonate 1,000 mg/day plus vitamin D3 4,000 units).(Shapiro 2016)

Asthma

Clinical data

In a randomized, double-masked, parallel-group trial in adults with symptomatic asthma and low vitamin D3 levels in whom previous treatment had failed, addition of high-dose vitamin D3 (100,000 units for 1 dose, then 4,000 units/day for 28 weeks) to inhaled corticosteroid therapy (ciclesonide 320 mcg/day) did not alter the rate of first treatment failure/exacerbation or overall treatment failure.(Castro 2014) These results were also supported by the randomized, placebo-controlled ViDiAs trial (N=250) in which adults with asthma managed with inhaled corticosteroids and who were at high risk of upper respiratory tract infection experienced similar rates of asthma exacerbation and upper respiratory tract infection regardless of vitamin D3 intervention (a bolus of vitamin D3 3 mg [120,000 units] every 2 months for 12 months).(Martineau 2015)

A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 7 high-quality studies (7 trials [N=955]) was conducted to evaluate oral vitamin D2 or D3 supplementation in patients with asthma. Results revealed that vitamin D supplementation resulted in a significant reduction in asthma exacerbations that required systemic corticosteroid treatment overall (P=0.03), but not among a subgroup of patients with at least 1 exacerbation at baseline; no benefit was seen in the time to first exacerbation. Subgroup analyses of moderate-quality patient data demonstrated significant reductions in asthma exacerbations in patients with baseline vitamin D levels below 25 nmol/L (P=0.046) but not in those with higher baseline levels. A reduction in admissions to the emergency department, hospital, or both was also observed for patients receiving vitamin D with at least 1 asthma exacerbation at baseline (P=0.03). Doses varied from daily doses of 500 to 2,000 units to a bolus dose of 100,000 units given every 2 months, with treatment durations ranging from 15 weeks to 1 year.(Jolliffe 2017)

The updated British guideline on the management of asthma (2019) summarized high-quality, robust evidence that suggested a reduction in severe asthma exacerbations in adults with mild to moderate asthma who received vitamin D supplementation. However, it was unclear if benefit was confined to people with lower baseline vitamin D status. Additionally, high-quality case-control and/or cohort studies indicated that vitamin D deficiency is a factor associated with an increased risk of future asthma attacks in school-aged children. Further research is needed to clarify these effects.(SIGN 2019)

Bacterial vaginosis

Clinical data

A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study evaluated the effect of high-dose vitamin D supplementation on recurrence of bacterial vaginosis in women being treated at an urban sexually transmitted disease clinic (N=118). Despite an increase in serum 25(OH)D with vitamin D supplementation (50,000 units for 9 doses over 24 weeks), recurrence of bacterial vaginosis was not reduced.(Turner 2014)

Cancer

Animal and in vitro data

Preclinical and epidemiologic studies have shown an effect of vitamin D on a variety of cancer cell lines. Cell cycle interruption, apoptosis, and other mechanisms have been demonstrated.(Chiang 2009, Kulie 2009, Trump 2010)

Clinical data

Meta-analyses of observational studies suggest a lower incidence of cancer with higher vitamin D serum levels.(Bischoff-Ferrari 2010, Gupta 2009, Kulie 2009) Particular attention has focused on breast, colon, and prostate cancer. In the Women's Health Initiative study, no association was found between vitamin D levels and breast cancer risk,(Chlebowski 2008) while the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study suggested a decreased risk of cancer with increasing 25(OH)D levels.(Kulie 2009, Trump 2010) In a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of vitamin D supplementation on overall mortality risk, a subgroup analysis (13 studies) of long-term vitamin D supplementation for at least 3 years revealed a significant reduction in cancer mortality (risk ratio=0.88; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.98).(Zheng 2013)

The American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline adaptation for the screening, assessment, and management of fatigue in adult survivors of cancer (2014) notes that results from small pilot studies on the effectiveness of supplements, such as vitamin D, for managing cancer-related fatigue are equivocal.(ASCO [Bower 2014])

Cardiovascular effects

Vitamin D is thought to exert cardiovascular effects by a number of mechanisms, including effects on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, homeostasis of calcium, and secondary effects on hyperparathyroidism and insulin resistance.(Pilz 2009)

Clinical data

In the Women's Health Initiative randomized trial, no clinically important effect on coronary or cerebrovascular risk or outcomes was found with vitamin D plus calcium supplementation over 7 years.(Hsia 2007, Margolis 2008) Other systematic reviews of clinical trials have largely found no effect of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular outcomes and hypertension.(Beveridge 2015, Pittas 2010, Witham 2009) In a meta-analysis evaluating the effects of vitamin D supplementation on overall mortality risk, a subgroup analysis of 13 studies of long-term vitamin D supplementation for at least 3 years revealed no reduction in cardiovascular mortality.(Zheng 2013)

An ancillary study within the Vitamin D and Omega-3 (VITAL) trial (N=25,871) found no significant effect of vitamin D (as vitamin D3 2,000 units administered daily with or without omega-3 fatty acids for a median follow-up duration of 5.3 years) on incident atrial fibrillation compared with placebo in adults without prior vascular disease; results remained nonsignificant in sensitivity and nonadherence analyses. Subgroup analyses revealed elevated hazard ratios with vitamin D compared with placebo in participants with a baseline age younger than the median of 66.7 years (P=0.02) and in those who consumed less than 1 drink per day (P=0.01). Combining omega-3 fatty acids with vitamin D3 resulted in no significant treatment effect.(Albert 2021)

Cystic fibrosis

Population-based studies support an association between circulating vitamin D levels and lung function.(Hughes 2009) The use of vitamin D in cystic fibrosis is based on knowledge of vitamin insufficiency due to pancreatic insufficiency; however, evidence of benefit is lacking for vitamin D supplementation despite routine use.(Ferguson 2009)

Dementia/Depression

Clinical data

A role for vitamin D in neuroprotection has been suggested. Vitamin D exerts antioxidant effects, and receptors are found in the human cortex and hippocampus. Correlations between Mini-Mental State Examination scores and vitamin D serum levels, as well as global cognitive function, have been shown.(Annweiler 2009, Grant 2009, Kulie 2009) One clinical trial demonstrated an improvement in mild depression with vitamin D supplementation.(Bertone-Johnson 2009)

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) guideline watch for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer disease and other dementias (2014) did not find enough definitive new evidence to support the use of vitamin D or change the 2007 guideline recommendations for alternative agents.(APA [Rabins 2017]) The Veteran’s Affairs and Department of Defense (VA/DoD) clinical practice guideline for the management of major depressive disorder (MDD) (2022) recommends against the use of vitamin D for treatment of MDD (weak).(VA/DoD 2022)

Dermatologic effects

Atopic eczema/Dermatitis

Clinical data

In a 2012 Cochrane review, 2 randomized controlled trials evaluating vitamin D for atopic eczema/dermatitis met criteria for analysis. Vitamin D supplementation alone did not provide benefit over placebo in any of the primary, secondary, or tertiary outcomes. However in a parallel-group design study (N=53; 13 to 45 years of age), vitamin D (cholecalciferol 1,600 units) and vitamin E (600 units alpha-tocopherol) combination therapy resulted in a significant difference in severity scores at the end of a 60-day treatment, as well as improvement in dryness, pruritus, and erythema compared with placebo.(Bath-Hextall 2012) In a 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis of observational and interventional trials that included adults and children, vitamin D levels were significantly lower in patients with atopic dermatitis versus healthy controls, with subanalysis by age also showing significantly lower serum vitamin D levels in children with atopic dermatitis versus healthy controls; however, heterogeneity was very high (99%) (11 studies [n=1,860]). Pooled data from the interventional studies showed significant improvement in severity of atopic dermatitis with vitamin D supplementation (weighted mean doses of all trials were 1,500 to 1,600 units/day) compared with placebo, with mean differences of −21 points (P<0.0001) in repeated measures interventions (2 studies [n=84]; no heterogeneity) and −11 points (P<0.0001) in randomized controlled trials (3 studies [n=96]; low heterogeneity).(Hattangdi-Haridas 2019)

Pruritus

Clinical data

A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (N=50) assessing use of ergocalciferol in patients with uremic pruritus was 1 of 10 new studies added to the 2016 updated Cochrane systematic review of pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care. After either oral ergocalciferol 50,000 units/week or placebo for 12 weeks, no differences were found between groups in pruritus values.(Siemens 2016)

Psoriasis

A role for vitamin D in the treatment of psoriasis has been suggested. Topical synthetic vitamin D (eg, tacalcitol) may be an alternative to topical steroids and may inhibit keratinocyte proliferation, as well as influence immune modulation.(Bikle 2010, Miller 2010, Tanghetti 2009)

Clinical data

The joint American Academy of Dermatology and National Psoriasis Foundation (AAD-NPF) Guidelines of Care for the Management and Treatment of Psoriasis With Topical Therapy and Alternative Medicine Modalities for Psoriasis Severity Measures (2020) states that use of topical vitamin D analogues are beneficial and recommended in treatment of psoriasis, including as part of a combination regimen (eg, with corticosteroids); rare systemic adverse effects include hypercalcemia and calcinuria.(AAD-NPF [Elmets 2021])

Diabetes

Studies suggest vitamin D exerts effects on the homeostasis of glucose metabolism.(Kulie 2009, Ozfirat 2010) A direct effect on insulin secretion has been suggested, as well as effects on insulin receptor expression, insulin sensitivity, and direct action on insulin itself.(Baz-Hecht 2010, Kulie 2009, Teegarden 2009)

Animal data

Vitamin D supplementation in animals has led to decreases in plasma glucose.(Kulie 2009, Ozfirat 2010)

Clinical data

Epidemiological data suggest a role of vitamin D in reducing the incidence of diabetes. Some evidence suggests vitamin D supplementation in infants is associated with a decreased risk of type 1 diabetes, and a meta-analysis has demonstrated an association between low vitamin D status and the prevalence of type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome.(Kulie 2009, Pittas 2010) However, a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials conducted in overweight/obese adults and children demonstrated no effect of vitamin D on blood glucose or insulin resistance(Jamka 2015).

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluating vitamin D supplementation on insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes and vitamin D deficiency (N=86), a correlation was observed between vitamin D levels and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), with the lowest HbA1c levels occurring in patients with 25(OH)D levels greater than 20 ng/mL.(Strobel 2014) However, in this trial and another randomized controlled trial in a similar population (N=158), neither blood glucose nor HbA1c was affected by 6-month supplementation of vitamin D (approximately 2,000 units/day).(Ryu 2014, Strobel 2014)

A small cross-sectional study conducted in Egypt assessed the effect of vitamin D deficiency on the risk of developing peripheral neuropathy in 60 patients with type 2 diabetes. Of the 45 patients with preexisting peripheral neuropathy, the majority (88.9%) had deficient or insufficient 25(OH)D levels at baseline, while of the 15 patients with no peripheral neuropathy, 26.7% had deficient or insufficient 25(OH)D levels (P<0.001). Unadjusted and multivariate adjusted analyses of data from nerve conduction tests revealed vitamin D levels were an independent risk factor for diabetic peripheral neuropathy, with respective ORs of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.79 to 0.93; P<0.001) and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.78 to 1; P=0.041). Additional independent risk factors included 2-hour postprandial blood sugar (P=0.042), HbA1c (P=0.004), and duration of diabetes (P=0.016).(Aziz 2021)

In a retrospective study of male patients with type 2 diabetes, a correlation was noted between vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency and occurrence of erectile dysfunction; HbA1c levels in patients with severe erectile dysfunction were significantly higher than in other groups.(Arıman 2021)

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials assessed the effect of vitamin D supplementation with or without calcium in 1,181 overweight and obese (body mass index range, 23 to 47 kg/m2) participants (10 trials in adults, 2 in children and adolescents). Doses of vitamin D alone ranged from 1,000 to 12,000 units/day given for a duration ranging from 12 to 52 weeks; 5 of the studies administered vitamin D (125 to 12,000 units/day) with calcium (500 to 1,200 mg/day). Results showed no effect of vitamin D on mean fasting insulin levels, blood glucose levels, or insulin resistance. These results held true for subanalyses to determine the effects of vitamin D dose, duration of therapy, and baseline 25(OH)D levels.(Jamka 2015) Another systematic review and purported meta-analysis of 18 cross-sectional studies (N=16,150) assessed the correlation of vitamin D status and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes. The authors reported an overall significant inverse effect of vitamin D levels on HbA1c (P=0.001). No data were provided; a 95% CI of −0.23 to −3.268 was given for an unidentified measure.(Al-Ibrahimy 2021)

The American Diabetes Association updated guidelines on the standards of medical care in diabetes (2021) recommends individualized medical nutrition therapy program as needed to achieve treatment goals for all people with type 1 or 2 diabetes, prediabetes, and gestational diabetes (level A). However, they generally recommend against the use of dietary supplementation with vitamins and minerals, including vitamin D, for glycemic control based on the lack of clear evidence that it improves outcomes in diabetics who do not already have underlying deficiencies (level C). They also note that studies have shown no efficacy of vitamin D in the prevention of diabetes.(ADA 2021a, ADA 2021b)

Falls in elderly individuals

Clinical data

Systematic reviews have been conducted to evaluate effects of supplemental vitamin D on the risk of falls in individuals 65 years or older.(Bischoff-Ferrari 2009, Kulie 2009) In a dose-stratified analysis, a dose of 800 units/day) reduced the risk of falls compared with placebo (72% lower incidence rate ratio), while lower doses of vitamin D did not significantly change the rate of falls compared with placebo; pooled results from reviews of randomized, controlled trials showed a significant 22% decrease in fall risk. The evidence-based review stated that supplementation with vitamin D 800 to 1,000 units/day should be part of any fall prevention program.(Kulie 2009) In a meta-analysis of 9 randomized clinical trials (N=22,012), intermittent high doses (annual dose greater than 100,000 units or intervals longer than 1 month) were not shown to reduce falls or fractures in adults 65 years and older.(Zheng 2015)

GI effects

Clinical data

In a 2×2 factorial randomized, placebo-controlled study in 100 adult women with irritable bowel syndrome, significant improvements in adjusted mean symptom severity scores occurred in women who received vitamin D (50,000 units of cholecalciferol) once biweekly for 6 weeks compared with those who did not (P=0.047). Additionally, severity of abdominal pain (P=0.012), duration of abdominal pain (P=0.009), and life disruption (P<0.005) were all significantly improved with vitamin D compared with placebo, with some data suggesting a synergistic effect with coadministration of soy isoflavones and vitamin D.(Jalili 2016)

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) updated guidelines for C. difficile infection in adults and children (2017) does not make specific recommendations regarding use of vitamin D for protecting against C. difficile infections; however, it notes that low levels of vitamin D are an independent risk factor among general patients with community-associated disease, older patients, and those with underlying inflammatory bowel disease.(McDonald 2018)

Immune function/Respiratory infections

Vitamin D receptors are ubiquitous in the body and are found in immune system–related cells, such as B and T lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages. A role for vitamin D on immune response is emerging.(Bischoff-Ferrari 2010, Chesney 2010, Walker 2009)

Clinical data

The Randomized Evaluation of Calcium or Vitamin D (RECORD) trial investigated the effect of vitamin D supplementation (800 units/day) on self-reported infections and antibiotic use but did not find a statistically significant association.(Avenell 2007) A single dose of vitamin D demonstrated an enhanced immune response in a randomized clinical trial in tuberculosis patients,(Martineau 2007) while a systematic review of clinical trials evaluating the effect of vitamin D supplementation (largely in tuberculosis, influenza, and other viral infections) concluded that further studies are warranted.(Yamshchikov 2009)

Vitamin D appears to be capable of inhibiting the pulmonary inflammatory response and enhancing pulmonary defense against pathogens.(Hughes 2009) A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 25 high-quality double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted across 15 countries (N=10,933; age range, 0 to 95 years) demonstrated an overall beneficial effect of vitamin D3 supplementation in reducing the risk of acute respiratory infections (ie, colds, flu, chest infections). Individual patient data were pooled and demonstrated statistically significant reductions in the percentage of patients experiencing at least 1 acute respiratory infection (NNT=33; P=0.003) and the rate of infections (P=0.04), but not in the time to first infection. Benefit was strongest for the subgroup with low baseline vitamin D levels (less than 25 nmol/L) (NNT=8; P=0.002) and when vitamin D was given daily or weekly without a bolus. Additional subgroup analyses showed a reduced rate of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in patients with low baseline vitamin D levels and in asthma exacerbations requiring systemic corticosteroids (P=0.046) in patients regardless of baseline vitamin D levels. No increase in risk of serious adverse events was observed with supplementation. Daily doses among studies ranged from less than 800 to more than 2,000 units/day given for a duration of 7 weeks to 1.5 years.(Martineau 2019)

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of hospitalized patients with moderate to severe COVID-19 and flu syndrome in Brazil (N=240), a single high dose of vitamin D3 200,000 units administered at a mean of 10 days (range, 6 to 14.6 days) after symptom onset led to significant increases in serum levels (+22.7 ng/mL; P<0.001) compared with placebo. The primary objective was to assess the effect of a single oral high dose of vitamin D3 on length of hospital stay. The majority of patients were either overweight (30%) or obese (56%) with comorbid diseases, such as hypertension (53%), diabetes (35%), and/or cardiovascular disease (13.5%). Ethnicity was predominantly White (55%) or mixed (31%), and at baseline 115 patients were 25(OH)D deficient. COVID-19 diagnosis was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction testing (62%), or by CT scan (59.5%; at least 50% bilateral multifocal ground-glass opacity) at time of enrollment; remaining patients had diagnosis confirmed by serology assay to detect IgG against SARS-Cov-2 at some point during the hospital stay. Mean differences between vitamin D3 and placebo were not statistically significant regarding hospital length of stay (7 days each group), in-hospital mortality (7.6% vs 5.1%, respectively), admission to intensive care unit (ICU) (16% vs 21.2%), or mean duration of mechanical ventilation (15 vs 12.8 days). The almost 2-fold reduction in need for mechanical ventilation seen with vitamin D3 was also not statistically significantly different from placebo (7.6% vs 14.4%, respectively). These outcome results remained consistent in the post hoc subgroup analysis of patients with or without baseline vitamin D deficiency. Posttreatment total calcium, creatinine, C-reactive protein, and D-dimer were similar between groups. No serious adverse events were reported and treatment was well tolerated; vomiting after vitamin D administration occurred in 1 patient.(Murai 2021)

In a large, quadruple-blind, randomized, placebo (corn oil)-controlled study conducted in Norway (N=37,741), no significant difference was found in positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test results (1.31% vs 1.32%), serious covid-19 infections (0.70% vs 0.58%), admissions to hospital for covid-19 (n=8 vs n=9), admissions to the ICU for covid-19 (n=4 each), more than 1 negative SARS-CoV-2 test (49.5% vs 49.4%), or at least 1 acute respiratory tract infection (22.9% vs 22.1%) among generally healthy participants who consumed low-dose vitamin D supplementation via cod liver oil versus those taking placebo. Overall, the majority of patients had no chronic disease (73.4%), had more than 30 hours of sun exposure from July to October 2020 (58.4%), and did not take vitamin D supplements (75.5%), but consumed fatty fish at least 1 to 2 days/week (61.5%) and had never smoked (51.4%). Their mean body mass index (BMI) at baseline was 26.1, 64.6% were female, 2.1% had a positive antibody test, and 35.6% reported having at least 1 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine during the study period, which ran from December 21, 2020 through June 2, 2021. These effects were not modified by covariates of sex, age, BMI, skin type, sun exposure, use of vitamin D supplements, vaccination status, consumption of fatty fish, or strict compliance. The intervention was 5 mL/day cod liver oil that provided vitamin D 10 mcg, EPA 0.4 g, DHA 0.5 g, vitamin A 250 mcg, and vitamin E 3 mg, whereas the corn oil placebo provided vitamin A 15.8 mcg and vitamin E 38 mg. Although no statistically significant difference was found in blood levels of 25(OH)D3 between groups, the significant reduction in 25(OH)D3 observed in the placebo group in winter (−12.5 nmol/L; P<0.001) was prevented in the cod liver oil group (+15 nmol/L; P<0.001). Additionally, cod liver oil led to a significant increase in omega-3 index by 1.9% (P<0.001), while placebo led to a significant decrease (−0.5%; P<0.001). The incidence and types of side effects were similar between groups.(Brunvoll 2022)

Insulin-like growth factor effects

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (6 studies [N=773]) evaluated effects of vitamin D supplementation on insulinlike growth factor 1 (IGF-1) in adults. Only 2 trials enrolled patients with vitamin D deficiency; diagnoses of participants included growth hormone deficiency, hyperparathyroidism, prediabetes, hypertension, overweight/obesity, and bedridden status in elderly patients. Supplementation ranged from 5,000 to 85,300 units/week for 8 to 52 weeks. No effect of vitamin D supplementation was found on IGF-1 in adults. The overall quality of included studies was rated as fair to poor.(Meshkini 2020)

Liver disease

Clinical data

A Cochrane systematic review identified 15 randomized controlled trials (N=1,034) of very low quality that assessed the effect of vitamin D supplementation (any dose, duration, route of administration) on adults with chronic liver diseases. Meta-analyses revealed studies with imprecise data, insufficient numbers of patients, high risk of bias, a lack of data on clinically relevant outcomes, and too much heterogeneity to allow for results to be drawn with any certainty. The authors concluded that effects of vitamin D supplementation on all-cause mortality, liver-related mortality, liver-related morbidity, and health-related quality of life are uncertain. In the update to this Cochrane systematic review, 12 trials (n=945) were added, with further assessment to evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of vitamin D supplementation in adults with chronic liver disease. Similar to the earlier review, the evidence regarding the effects of vitamin D (vs placebo or no intervention) on all-cause mortality, liver-related mortality, or serious adverse events was uncertain.(Bjelakovic 2017, Bjelakovic 2021)

The association between low vitamin D concentration and an increased risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), defined more recently as metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), was explored in a retrospective observational study in patients who underwent a routine health examination in Korea. Among 1,202 participants, mean age was 57 years, and most (60.6%) were male. Participants with vitamin D deficiency (less than 20 ng/mL) were younger, more often obese (BMI at least 25 kg/m2), were current smokers, and had higher waist circumference, lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL), higher total cholesterol and triglycerides, and higher prevalence of NAFLD (P<0.05) than participants with vitamin D sufficiency. In the NAFLD analysis, vitamin D sufficiency was associated with a decreased risk of NAFLD when adjusted for age and gender compared with participants who had vitamin D deficiency (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.91). Multivariate analysis of confounding factors including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, BMI, smoking, and HDL resulted in a nonsignificant lower risk of NAFLD in patients with vitamin D sufficiency compared to those with vitamin D deficiency. When the association between MAFLD and vitamin D level was investigated among the eligible 1,308 patients, although the significance attenuated, results were similar to NAFLD data. Patients with severe steatosis had a significantly lower prevalence of vitamin D sufficiency (P=0.008).(Heo 2021) In a cross-sectional study of 2,538 obese Chinese adults (BMI at least 24 kg/m2) who underwent a health check-up, vitamin D levels were statistically significantly lower in obese patients with NAFLD (59.03 nmol/L) compared with obese patients without NAFLD (63.56 nmol/L) (P<0.001). No difference in vitamin D levels was found in patients who were not obese with or without NAFLD. In patients who were obese, vitamin D levels (quartiles as well as adequacy of levels) were negatively associated with the prevalence and risk of NAFLD.(Wang 2021)

Migraine prophylaxis

Of the 18 trials identified in a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials that assessed vitamins and minerals for migraine prophylaxis, only one study administered vitamin D. As data could not be pooled, more high-quality studies are needed to draw conclusions for the use of vitamin D in migraine prophylaxis.(Okoli 2019)

Mortality

Clinical data

A meta-analysis of 32 studies published and indexed between 1966 and 2013 evaluated the relationship between 25(OH)D and all-cause mortality in healthy participants as well as patients in clinic cohorts. The age-adjusted death rate in individuals with vitamin D levels in the lowest quantile (0 to 9 ng/mL) was almost twice that of those in the highest quantile (more than 35 ng/mL). The pooled dose-response curve declined steeply between 0 ng/mL and 30 to 39 ng/mL and flattened at greater than 50 ng/mL, with all-cause mortality being significantly higher when levels were less than 30 ng/mL (P<0.01).(Garland 2014) Similarly, a meta-analysis (42 intervention randomized controlled trials; N=85,466) identified a decrease in all-cause mortality when vitamin D supplementation was continued for 3 years or longer (P=0.001); heterogeneity was insignificant. In a subgroup analysis of long-term follow-up studies, benefits were observed in patients younger than 80 years, those receiving a dose of 800 units or less, and patients with a baseline 25(OH)D level less than 50 nmol/L. One subgroup analysis of 13 studies revealed that vitamin D plus calcium was effective in reducing mortality compared with placebo but was not significantly effective when compared with calcium only; effect of vitamin D alone was not significant compared with placebo.(Zheng 2013)

Multiple sclerosis

Clinical data

Theoretical and epidemiological models support a place in therapy for vitamin D in multiple sclerosis (MS). An inverse relationship has been demonstrated between vitamin D levels and MS, especially in patients younger than 20 years of age, while the development of MS in women has been associated with low 25(OH)D levels. Lower serum vitamin D in patients with MS is associated with more severe disability; lower levels during relapses have also been reported in patients with relapse-remitting MS.(Kulie 2009, Myhr 2009, Pierrot-Deseilligny 2009, Sioka 2009) In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in adults diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS (N=94), high-dose vitamin D supplementation (50,000 units every 5 days for 3 months) produced a significant improvement in mental health and health change quality of life scores compared to placebo (P=0.041 and P=0.036, respectively).(Ashtari 2016)

Limited prospective data exist; however, a small clinical study in MS patients (N=12) showed a decrease in the number of lesions on magnetic resonance imaging after administration of vitamin D 1 mg (40,000 units) daily over 28 weeks.(Kulie 2009) No serious adverse events were reported at this dosage, and no hypercalcemia or hypercalciuria was reported.

Osteoarthritis

Clinical data

The American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation (ACR/AF) guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee (2019) conditionally recommends against the use of vitamin D in patients with knee, hip, and/or hand osteoarthritis (low- to very low–quality evidence). Risk versus benefit is fairly well balanced and necessitates a shared decision between the patient and clinician.(ACR/AF [Kolasinski 2020]) The updated American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee (2021) recommends that vitamin D may be helpful in reducing pain and improving function for patients with mild to moderate osteoarthritis of the knee (limited).(Brophy 2022)

Osteoporosis

Clinical data

An updated meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation reviewed randomized controlled trials published between July 1, 2011 and July 31, 2015 that compared effects of supplementation with vitamin D plus calcium on fracture prevention in adults. Results were based on 30,970 participants (most of whom were community dwellers) reporting 195 total hip fractures and 2,231 total fracture events. Calcium doses ranged from 1,000 to 1,200 mg/day (except for 500 mg/day in 1 study), vitamin D was dosed at 700 to 800 units/day (except for 400 units/day in 1 study), and follow-up ranged from approximately 1 to 7 years. Findings corroborated previous reports: Subanalysis of 8 trials identified a 15% reduction in the incidence of total fractures, with a summary relative risk estimate (SSRE) of 0.85 (95% CI, 0.73 to 0.98). Similarly, a 30% reduction in risk of hip fractures was found in subanalysis of 6 trials (SSRE, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.56 to 0.87). Risk reduction in hip fractures was significant for institutionalized participants (2 studies) and borderline statistically significant in community-dwelling participants (38% reduction; 4 studies). Statistical significance held true after one-study-removed influence analysis, with SSREs ranging from 0.64 to 0.73.(Weaver 2016) In contrast, in a meta-analysis of 9 randomized clinical trials (N=22,012), intermittent high doses of vitamin D (annual dose greater than 100,000 units or intervals longer than 1 month) did not reduce fractures in adults 65 years and older.(Zheng 2015)

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists updated guidelines for the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis (2022) recommend that patients receiving osteoporosis pharmacotherapy and those with postmenopausal osteoporosis who cannot tolerate pharmacologic therapy be counseled to consume the recommended daily allowance of calcium and vitamin D preferably through diet, but also with supplementation, or both (Good Practice Point).(ACOG 2022) The North American Menopause Society's updated position statement on the management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women (2021) recommends adequate intakes of calcium and vitamin D when taking osteoporosis drugs to reduce the risk of treatment-induced hypocalcemia. They also note that vitamin D deficiency is a medical condition that can adversely affect bone health; however, the skeletal benefits of vitamin D supplementation in healthy adults are uncertain.(NAMS 2021)

Parkinson disease

Clinical data

An association between vitamin D status and Parkinson disease was explored in a systematic review and meta-analysis of 8 studies (including 2 randomized controlled trials). All but 1 study were considered to be of high quality. Pooled data from 3 studies (n=1,779) with little to no heterogeneity indicated that both vitamin D insufficiency (less than 30 ng/mL) and deficiency (less than 20 ng/mL) were associated with a significant increase in the risk of Parkinson disease by 1.5- and 2.5-fold, respectively (P<0.001 each). The 2 randomized controlled trials (n=144; homogenous data) reported effects of vitamin D supplementation (1,200 units/day for 12 months, or 50,000 units/week plus 600 units/day for 6 months). Vitamin D levels increased significantly with supplementation (P<0.001; homogenous data), and disease risk was significantly reduced with at least 15 minutes of exposure to sunshine per week (P<0.001; high heterogeneity). Motor function in Parkinson patients was unaffected by vitamin D supplementation for up to 12 months.(Zhou 2019)

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Clinical data

Several systematic reviews have found limited robust data describing effects of vitamin D supplementation in patients with PCOS; data from meta-analyses of lower quality–studies are equivocal and usually not homogenous.(Arentz 2017, Azadi-Yazdi 2017, Fang 2017, Xue 2017)

A meta-analysis of 6 mostly low-quality studies (N=183) revealed that vitamin D supplementation reduced total testosterone levels significantly in before-after studies (P=0.02) but not randomized controlled trials. In contrast, no significant effect was seen on serum free testosterone levels or sex hormone binding globulin.(Azadi-Yazdi 2017) Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 16 studies of patients with PCOS, no significant effect of vitamin D supplementation was found on serum free or total testosterone, insulin resistance, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, or serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate. While a significant decrease in serum parathyroid hormone was observed with vitamin D (P=0.003), heterogeneity was significant among the 5 studies reporting this outcome. Results from a subgroup analysis revealed a significant reduction in triglycerides (P=0.03) with low-dose vitamin D (less than 50,000 units).(Xue 2017) Pooled data of secondary outcomes from 2 additional randomized controlled trials did not show an effect of vitamin D on metabolic hormones, lipid parameters, or C-reactive protein in 78 patients with PCOS.(Arentz 2017).

Pooled data from a meta-analysis of 9 randomized controlled trials (no significant heterogeneity) in patients with PCOS (N=502) showed that vitamin D supplementation (dosage range, 400 to 12,000 units/day) significantly increased the number of dominant follicles compared with no vitamin D (P=0.001); no changes in menstrual regularity were noted. In studies with higher heterogeneity, levels of 25(OH)D (P<0.001) and parathyroid hormone (P=0.01) were significantly improved, but no differences were found on glucose or lipid parameters.(Fang 2017)

Renal effects

As kidney function is impaired, the inability to maintain adequate phosphorus and calcium levels results in compensatory mechanisms involving parathyroid hormone. Resultant increases in bone metabolism to release calcium to the system cause bone deformation, pain, and an increased risk of fractures. Supplementation of vitamin D suppresses parathyroid hormone, but it may also slow the progression of chronic kidney disease via novel pathways. Vitamin D analogues, such as paricalcitol, may exert anti-inflammatory effects, as well as affect the renin-angiotensin systems and decrease morbidity and mortality. However, studies are limited.(Li 2009, Palmer 2009, Williams 2009)

Clinical data

In a randomized, double-blind trial in patients receiving chronic dialysis (N=50), no improvement in 24-hour blood pressure, arterial stiffness, or cardiac function was observed in patients treated for 6 months with vitamin D 75 mcg (3,000 units) or placebo. However, left ventricular end-diastolic function was increased significantly in the treatment group (P=0.024).(Mose 2014)

In a 2016 updated Cochrane systematic review of pharmacological interventions for pruritus in adult palliative care, a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (one of 10 new studies added) evaluated administration of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) in 50 patients undergoing hemodialysis with uremic pruritus, possibly due to impaired vitamin D metabolism. After 12 weeks of either ergocalciferol 50,000 units or placebo administered orally each week, no differences were found between groups in pruritus values.(Siemens 2016)

Rheumatic diseases

Clinical data

Robust data are lacking to determine the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in rheumatic diseases. A systematic review of studies assessing vitamin D and its analogues for rheumatic diseases identified 9 randomized, placebo-controlled trials with sample sizes ranging from 6 to 340 patients. The identified studies included patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (3 studies), rheumatoid arthritis (5 studies), or systemic sclerosis (1 study). Only 7 met criteria for inclusion in the meta-analyses (N=1,161). Regimens employed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or SLE included cholecalciferol 2,000 or 4,000 units/day for 3 months, 2,000 units/day for 12 months, and 50,000 units/week for 3 or 6 months. Vitamin D supplementation in patients with SLE was associated with a significant reduction in anti-dsDNA positivity (3 studies [n=361]), with a risk difference of −0.1 (95% CI, −0.18 to −0.03; P=0.005; 0% heterogeneity). In contrast, vitamin D supplementation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis was not associated with significant reductions in visual analog scale or disease activity score (2 studies [n=120]) or in recurrence (2 studies [n=252]); little to no heterogeneity was observed.(Franco 2017)

Sickle cell disease

Clinical data

A 2020 updated Cochrane review including 3 randomized controlled trials of varying quality compared oral administration of any form of vitamin D supplementation with another type or dose of vitamin D or with placebo in patients with sickle cell disease. One of the studies (a double-blind randomized controlled trial of 25 adults or children who completed the full 6 months of follow-up) showed low-quality evidence of fewer pain days (mean difference, −10 days) at week 8 but worse health-related quality of life at weeks 16 and 24 with vitamin D3 supplementation compared with placebo. Moderate-quality data from a randomized controlled trial of 21 patients who received vitamin D3 12,000 units/month or 100,000 units/month for 24 months demonstrated more episodes of acute chest syndrome at year 1 and little to no difference in pain or forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1) at year 1 or 2 with high-dose vitamin D3 compared with the lower dosage. The high-dose group experienced lower values for forced vital capacity at years 1 and 2; little to no difference was observed between dosing regimens in muscle health. For the third study (a double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing oral vitamin D3 4,000 units/day with 7,000 units/day [n=62]), data were not available for analysis. In all 3 analyses, vitamin D supplementation likely led to higher serum vitamin D levels.(Soe 2020)

Vaccine efficacy

Clinical data

The results of 3 sub-studies nested within the CORONAVIT phase 3 open randomized, controlled trial in the UK revealed that the protective efficacy of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (n=2,808), the post-vaccine titers of anti-spike antibodies (n=1,853), or neutralizing antibody titers and antigen-specific cellular responses to SARS-CoV-2 (n=101) were affected by vitamin D supplementation. Patients received a vitamin D test and a 6-month supply of 3,200 units/day (n=1,550) or 800 units/day (n=1,550) vitamin D if their blood 25(OH)D level was less than 75 nmol/L, or they received no test or supplementation (n=3,100). Vaccine efficacy was determined among patients who had at least 2 doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (n=2,808). Overall the median age was 61.9 years and the majority were female (65.8%) and White (96.4%), with a BMI less than 30 kg/m2 (80.3%) and self-reported health as very good to excellent (64.7%).(Joliffe 2022)

Vegetarian diet

Clinical data

The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics' updated position paper on vegetarian diets (2016) states that adequate nutrition can be provided by a well-planned vegetarian diet that includes legumes. Therapeutic vegetarian diets are useful in maintaining a healthy weight and BMI and are associated with a reduction in cardiovascular disease risk and type 2 diabetes. Vitamin D supplements are recommended, especially in older adults, if sun exposure and vitamin D-fortified foods are insufficient.(Melina 2016)

Vitamin D deficiency

Clinical data

The 2016 Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (ANDA) updated position statement on vegetarian diets states that vitamin D intake is lower among some vegans and vegetarians than nonvegetarians. Vitamin D supplementation is recommended in vegetarians and vegans, including during pregnancy and breastfeeding, if sun exposure and intake of fortified foods are insufficient to maintain healthy levels. Additionally, older adults have decreased cutaneous production of vitamin D, so supplementation is recommended.(Melina 2016)

A review of guidelines that addressed nutrition, physical activity, and nutrient supplementation before and after bariatric surgery identified one guideline that included recommendations for micronutrients: the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery Integrated Health Nutritional Guidelines for the Surgical Weight Loss Patient 2016 Update: Micronutrients. Vitamin D supplementation was recommended following weight loss bariatric surgery, based on serum vitamin levels, at a dose of 3,000 units of vitamin D3 daily until blood levels of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL are attained (grade D evidence, best evidence level 4). It was also recommended that post−weight loss surgery vitamin D deficiency or levels insufficient to normalize calcium should be repleted (grade C evidence, best evidence level 3) at a dose of 3,000 to 6,000 units/day of D3, or 50,000 units of D2 1 to 3 times weekly (grade A evidence, best evidence level 1). Both D3 and D2 are both effective for vitamin D repletion, depending on the dosing regimen; however, D3 is more potent (grade A evidence, best evidence level 1).(Tabesh 2019)

To prevent vitamin D deficiency, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends infants and children receive at least 400 units/day of vitamin D from diet and supplements.(Bordelon 2009)

Dosing

Vitamin D3 20 mcg is equivalent to 800 units.(Avenell 2007) Vitamin D3 and D2 are both effective for vitamin D repletion, depending on the dosing regimen; however, D3 is more potent.(Tabesh 2019)

Clinical response to vitamin D does not always correspond with serum levels of 25(OH)D.(Kulie 2009) Generally a serum level of less than 20 ng/mL of 25(OH)D constitutes a deficiency in adults and children.(Bordelon 2009, Kulie 2009, NIH 2021)

Acute respiratory infections (cold, flu, chest infections)

In an individual patient data meta-analysis evaluating potential of vitamin D3 supplementation to reduce risk of acute respiratory infections in individuals 0 to 95 years of age, age-appropriate daily or weekly vitamin D3 supplementation without additional bolus doses was suggested to protect against acute respiratory infections, particularly in those with low baseline 25(OH)D levels (less than 25 nmol/L).(Martineau 2019)

Elderly

A study conducted to establish the vitamin D requirements in adults 64 years of age and older during the winter determined a recommended dose between 7.9 and 42.8 mcg daily to maintain a serum 25(OH)D level of 25 ng/mL(Cashman 2009); an evidence-based review recommends 800 to 1,000 units/day of vitamin D to reduce the risk of falls in older populations.(Kulie 2009)

Infants and children

To prevent vitamin D deficiency, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends infants and children receive at least 400 units/day of vitamin D from diet and supplements.(Bischoff-Ferrari 2009, Bordelon 2009, Kulie 2009)

Parkinson disease

Vitamin D3 50,000 units/week plus 600 units/day for 6 months, or 1,200 units/day for 12 months was used in a randomized controlled trial for prevention of vitamin D insufficiency (levels below 30 ng/mL) or deficiency (levels below 20 ng/mL), which can increase disease risk.(Zhou 2019)

Polycystic ovary syndrome

Vitamin D doses ranging from 400 to 12,000 units/day for various durations have been used in randomized controlled trials to increase the number of dominant follicles in patients with PCOS.(Fang 2017)

Post−weight loss bariatric surgery

A review of guidelines recommends vitamin D3 3,000 units daily until blood levels of 25(OH)D greater than 30 ng/mL are attained.(Tabesh 2019)

Post−weight loss surgery in patients with vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency

A review of guidelines recommends vitamin D3 3,000 to 6,000 units/day or vitamin D2 50,000 units given 1 to 3 times weekly.(Tabesh 2019)

Systemic lupus erythematosus

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, regimens employed in patients with SLE included cholecalciferol 2,000 or 4,000 units/day for 3 months, 2,000 units/day for 12 months, and 50,000 units/week for 3 or 6 months.(Franco 2017)

Pregnancy / Lactation

The safety and efficacy of vitamin D use in pregnancy have not been established. Clinical trials have evaluated the excretion of vitamin D in breast milk by mothers receiving vitamin D supplementation. Adequate levels of vitamin D are achieved in breastfeeding infants from mothers with a vitamin D intake of 400 units/day. All milk formulas sold in the United States contain at least 400 units/L of vitamin D.(Kulie 2009)

Data from 6 randomized controlled trials used to inform the World Allergy Organization-McMaster guidelines for prevention of allergies found no association with vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy and adverse events or lower-birthweight infants (2 studies [n=234]); overall certainty of the data was low to very low.(Yepes-Nuñez 2018)

Interactions

The use of statins has been shown to increase serum vitamin D levels.(Aloia 2007) Corticosteroids decrease the metabolism of vitamin D, and orlistat reduces absorption of vitamin D, while phenobarbital and phenytoin increase hepatic metabolism of vitamin D.(NIH 2021)

Aluminum hydroxide: Vitamin D analogues may increase the serum concentration of aluminum hydroxide. Specifically, the absorption of aluminum may be increased, leading to increased serum aluminum concentrations. Consider therapy modification.(Demontis 1986, Demontis 1989, Dovonex March 2015, Fournier 1985, Hectorol November 2018, Rayaldee December 2019, Rocaltrol November 1998, Sorilux May 2019, Vectical July 2020, Vitamin D October 2018, Zemplar October 2016, Zemplar May 2021)

Bile acid sequestrants: Bile acid sequestrants may decrease the serum concentration of vitamin D analogues. More specifically, bile acid sequestrants may impair absorption of vitamin D analogues. Consider therapy modification. Only orally administered vitamin D analogues are subject to this interaction.(Compston 1978, Heaton 1972, Hectorol December 2010, Hoogwerf 1992, Ismail 1990, Knodel 1987, One-Alpha March 2010, Rayaldee June 2016, Rocaltrol July 2009, Schwarz 1980, Thompson 1969, Watkins 1985, Welchol June 2013, West 1975, Zemplar October 2016)

Calcium salts: Calcium salts may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of vitamin D analogues. Monitor therapy.(Dovonex March 2015b, Ergocalciferol October 2018, Fosamax Plus D August 2019, Hectorol November 2018, One-Alpha September 2020, Rayaldee December 2019, Rocaltrol November 1998, Vectical July 2020, Zemplar May 2021b)

Cardiac glycosides: Vitamin D analogues may enhance the arrhythmogenic effect of cardiac glycosides. Monitor therapy.(Hectorol November 2018, Kanji 2012, Vella 1999)

Danazol: Danazol may enhance the hypercalcemic effect of vitamin D analogues. Monitor therapy.(Danocrine December 2011, Hepburn 1989)

Erdafitinib: Serum phosphate level–altering agents may diminish the therapeutic effect of erdafitinib. Consider therapy modification.(Balversa April 2019)

Mineral oil: Mineral oil may decrease the serum concentration of vitamin D analogues. More specifically, mineral oil may interfere with the absorption of vitamin D analogues. Consider therapy modification. Only orally administered vitamin D analogues are subject to this interaction.(Drisdol March 2007, Hectorol November 2018, One-Alpha March 2010, Zemplar October 2016)

Multivitamins/Fluoride (with ADE): Multivitamins/fluoride (with ADE) may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of vitamin D analogues. Avoid combination. Multivitamin products with higher doses of vitamin D pose a higher risk than those products with smaller doses of vitamin D.(Calcijex 2004, Dovonex April 2006, Drisdol March 2007, Fosamax Plus D March 2010, Hectorol December 2010, One-Alpha March 2010, Zemplar October 2016)

Multivitamins/Minerals (with ADEK, Folate, Iron): Multivitamins/minerals (with ADEK, folate, iron) may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of vitamin D analogues. Avoid combination. Multivitamin products with higher doses of vitamin D pose a higher risk than those products with smaller doses of vitamin D.(Calcijex 2004, Dovonex April 2006, Drisdol March 2007, Fosamax Plus D March 2010, Hectorol December 2010, One-Alpha March 2010, Zemplar October 2016)

Orlistat: Orlistat may decrease the serum concentration of vitamin D analogues. More specifically, orlistat may impair absorption of vitamin D analogues. Consider therapy modification. Monitor therapy. Only orally administered vitamin D analogues are subject to this interaction.(Xenical May 2010, Zemplar October 2016)

Sucralfate: Vitamin D analogues may increase the serum concentration of sucralfate. Specifically, the absorption of aluminum from sucralfate may be increased, leading to an increase in the serum aluminum concentration. Consider therapy modification.(Demontis 1986, Demontis 1989, Dovonex March 2015a, Fournier 1985, Hectorol November 2018, Rayaldee December 2019, Rocaltrol November 1998, Sorilux May 2019, Sucralfate February 2020, Vectical July 2020, Vitamin D October 2018, Zemplar October 2016, Zemplar May 2021a)

Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics: Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics may enhance the hypercalcemic effect of vitamin D analogues. Monitor therapy.(Brickman 1972, Coe 1988, Fosamax Plus D August 2019, Hectorol November 2018, Krause 1989, Lemann 1985, Nowack 1992, Rayaldee December 2019, Rejnmark 2001, Rejnmark 2003, Riis 1985, Rocaltrol November 1998, Santos 1986, Testa 2006, Vectical July 2020)

Vitamin D analogues: Vitamin D analogues may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of other vitamin D analogues. Avoid combination.(Hectorol November 2018, One-Alpha September 2020, Rayaldee December 2019, Rocaltrol November 1998, Vectical July 2020, Zemplar May 2021b)

Adverse Reactions

High doses of vitamin D have rarely produced adverse events in clinical trials.(Kulie 2009)

Prolonged sun exposure alone cannot cause vitamin D overdose because sunlight destroys excess vitamin D3.(Kulie 2009)

Toxicology

Toxicity due to vitamin D is considered to manifest at levels greater than 150 ng/mL of serum 25(OH)D. Symptoms of hypervitaminosis D include fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and weakness associated with hypercalcemia.(Kulie 2009, NIH 2021) Reports exist of toxicity in children administered high-dose vitamin D after World War II in Europe; hypercalcemia, nephrocalcinosis, adverse cardiovascular effects, early aging, and premature death were reported.(Tuohimaa 2009)

Hypervitaminosis D in 2 young brothers was reported subsequent to an overdose of an over-the-counter (OTC) vitamin D supplement that resulted from 2 simultaneous dosing errors: The OTC product Merluzzovis (cod liver oil−based supplement) contained approximately 1,000 times the labeled vitamin D content per capsule, and the mother administered twice the dose as recommended on the label. After 1 month of supplementation, the 12-year-old had received a total of 7,632,000 units (254,490 units/day instead of the recommended 400 units/day) and was hospitalized for abdominal pain, constipation, vomiting, hypercalcemia, suppressed parathyroid, and acute renal failure. The 15-year-old brother had received a total of 3,180,000 units over the previous 2 weeks, was asymptomatic, normocalcemic, and had normal renal function. Their vitamin D levels were well over the toxic lower limit (150 ng/mL) and were 535 ng/mL and 484.9 ng/mL, respectively. The 12-year-old was normocalcemic and had normal renal function within 1 month of discharge.(Conti 2014)

References

Disclaimer

This information relates to an herbal, vitamin, mineral or other dietary supplement. This product has not been reviewed by the FDA to determine whether it is safe or effective and is not subject to the quality standards and safety information collection standards that are applicable to most prescription drugs. This information should not be used to decide whether or not to take this product. This information does not endorse this product as safe, effective, or approved for treating any patient or health condition. This is only a brief summary of general information about this product. It does NOT include all information about the possible uses, directions, warnings, precautions, interactions, adverse effects, or risks that may apply to this product. This information is not specific medical advice and does not replace information you receive from your health care provider. You should talk with your health care provider for complete information about the risks and benefits of using this product.

This product may adversely interact with certain health and medical conditions, other prescription and over-the-counter drugs, foods, or other dietary supplements. This product may be unsafe when used before surgery or other medical procedures. It is important to fully inform your doctor about the herbal, vitamins, mineral or any other supplements you are taking before any kind of surgery or medical procedure. With the exception of certain products that are generally recognized as safe in normal quantities, including use of folic acid and prenatal vitamins during pregnancy, this product has not been sufficiently studied to determine whether it is safe to use during pregnancy or nursing or by persons younger than 2 years of age.

More about cholecalciferol

- Check interactions

- Compare alternatives

- Reviews (48)

- Latest FDA alerts (2)

- Side effects

- Dosage information

- During pregnancy

- Drug class: vitamins

- Breastfeeding

- En español

Patient resources

Related treatment guides

Further information

Always consult your healthcare provider to ensure the information displayed on this page applies to your personal circumstances.

Copyright © 2024 Wolters Kluwer Health